Colds and Conquests: How A Health Crisis May Have Spurred Roman Expansion

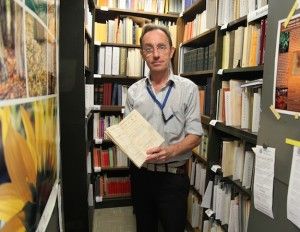

Smithsonian Research Associate Alain Touwaide will argue that a quest for medicinal plants may have spurred Roman expansion at his July 18 lecture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120717114011Office-Touwaide.jpg)

“Radishes are flatulent,” declared Pliny the Elder in Vol. 4 of his Natural History, “hence it is that they are looked upon as an ailment only fit for low-bred people.”

Pliny’s descriptions of the gardens and plants of ancient Rome and Greece offer some of the richest, and funniest, information concerning the medicinal uses of everyday plants in antiquity. They also provided researcher Alain Touwaide with a critical clue in his effort to explain Roman expansion as a quest for greater biodiversity.

“He complained that Romans were bringing nature into cities,” says Touwaide, a research associate in the Natural History Museum’s botany department. While Pliny admired Greece’s elaborate pleasure gardens, he lamented Rome’s urban ones, calling them “poor man’s fields.”

But, as Touwaide points out, these invasive gardens served a purpose, “They are smart, the Romans.”

Roman urbanization reached proportions unparalleled in the ancient world. As with all periods of rapidly growing populations, a health crisis emerged with the equally rapid transmission of illnesses. Touwaide and his fellow researcher and wife, Emanuela Appetiti, have been putting together data suggesting Roman expansion into the Mediterranean was actually driven by a need for more medicinal plants in response to this crisis.

A series of recent triumphs has helped cement their case. New technology allowed the team to investigate a Roman shipwreck discovered in the 1980s but dating back to 140-210 BC. On board were more than a hundred sealed vials as well as surgical tools. After analysis, Touwaide concluded most of the medicines were used to treat intestinal problems. “I saw that the extension of the Romans into the Mediterranean overlaps every single time with the acquisition of new medicines,” explains Touwaide.

The Romans were essentially hedging their bets: the proliferation of urban gardens allowed for the growth of popular medicinal treatments. But for the rarer, newer pathologies introduced as a result of urbanization and global trade; the Romans looked to the Near East.

“Thinking about all those elements, I came up with the idea that we have something very coherent. First, we have the trade of medicinal plants. Second, we have the growth of the cities, which is unprecedented in ancient history. Three, we see that the Romans are building gardens, which they hadn’t before. And four, we see that there is an incredible expansion of medicines.”

When he and his wife aren’t exploring long-buried treasures of the sea, they’re crisscrossing the globe to survey as many ancient manuscripts as possible.

For the past three years, Touwaide has traveled to the island of Patmos in the Aegean Sea. It’s “really at the end of the world,” according to Touwaide, “You have no airlines, so you have to go by sea.” Once there, he visits St. John’s Monastery to review its collection of manuscripts.

It’s worth the effort. Touwaide is one of only a handful of people who have had the privilege of reviewing the manuscripts.

His efforts to “follow the text,” now point in the direction of China. “We have discovered texts in Chinese in which the names of medicines are the Arabic names in the Arabic alphabet,” says Touwaide. “But these Arabic names are in fact the Greek names, which haven’t been translated, but have been transliterated into Arabic,” suggesting a long chain of transmission leading back to Greece. He has plans to investigate this connection next.

“I have a reputation to be always gone,” jokes Touwaide, “to be always somewhere else.”

This Wednesday, at least, he’ll be here at the Smithsonian giving a lecture titled “Ancient Roman Gardens as Urban Pharmacopeia.” Catch him while you can.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)