Reminders of September 11, 2001, are scattered throughout the Smithsonian Institution’s collections. A warped piece of steel taken from Ground Zero. A damaged mail collection box that once stood across the street from World Trade Center Building 5. An Airfone recovered from the wreckage of United Airlines Flight 93. A clock frozen at the moment an airplane crashed into the Pentagon, knocking the object off the wall.

Tangible traces of an American tragedy, these artifacts and others will feature heavily in the Smithsonian’s upcoming commemoration of 9/11. “After two decades, we continue to feel the lasting and complex personal, national and global ramifications of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001,” says Anthea M. Hartig, director of the National Museum of American History (NMAH), in a statement. “At the [museum], we commit to keeping the memory of that day alive by working with a wide range of communities to actively expand the stories of Americans in a post-September 11 world.”

From virtual events hosted by NMAH to new educational resources offered by the National Postal Museum (NPM), here’s how the world’s largest museum, education and research complex is marking the 20th anniversary of 9/11. Listings are organized by unit name.

National Museum of American History

To commemorate this year’s anniversary, NMAH created a digital portal called September 11: An Evolving Legacy. The platform reflects the museum’s shifting approach to telling the story of 9/11. “The idea here is that we broaden our approach,” says Cedric Yeh, curator of the museum’s National September 11 Collection. “We’re hoping to add to our current collections and include diverse experiences, not just … about the day and the immediate aftermath, but [about] the long-term effects on people’s lives.” (Read about 31 Smithsonian artifacts that tell the story of 9/11 here.)

Hidden Stories, Hidden Voices—a series of three free, online programs exploring stories “not typically told in the arc of” 9/11—will help fulfill this goal by expanding the “national narrative of September 11 and gain[ing] a more complete picture of the complexities and legacy of the day,” according to NMAH.

The first event, Portraits of Manhattan’s Chinatown, took place on September 1 and is now available to view online. Hosted in partnership with the Charles B. Wang Community Health Center and the Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA), the panel found members of Manhattan’s Chinatown community discussing the economic and social fallout of the attacks.

Reflecting on the challenges faced by the neighborhood today—chief among them the Covid-19 pandemic—Sandy Lee Kawano, CEO of Lee Insurance, said, “New York Chinatown has this amazing resilience. I feel we will prevail. We survived the flu pandemic of 1918, … 9/11, [Hurricane] Sandy, two World Wars. … Chinatown was able to maintain its identity and its economy despite immigration laws keeping our population down. We made it work.”

The series’ second event, Art in the Aftermath, is set for tonight at 7 p.m. Eastern time. (NMAH is hosting the program in collaboration with MOCA and El Museo del Barrio.) Artists working across a range of disciplines will share “how their experiences of September 11 shaped their artistry, community and the world at large,” according to the event description.

Finally, on Friday at 7 p.m. Eastern, Latinx Empowerment After the Attacks will discuss how members of New York’s Latino community are “navigating complex immigration policy, worsening health effects and socioeconomic challenges while serving the city as first responders, volunteers, organizers and caregivers.” Building on NMAH’s NYC Latino 9-11 Collecting Initiative, the event is co-hosted by the New York Committee for Occupational Safety and Health, the Consulate General of Mexico in New York and the Mexican Cultural Institute in Washington D.C. Register for the free panels on Eventbrite, or tune in via the museum’s Facebook or YouTube pages.

Launched in 2018 with funding from the Smithsonian Latino Center, the 9/11 Latino collecting initiative is also highlighted on the web portal. The site includes a list of new acquisitions and previously collected objects, including a sweatshirt worn by Ivonne Coppola Sanchez, a Puerto Rican first responder who searched for survivors at Ground Zero, and a portrait of Beatriz Susana Genoves, who worked as a greeter at the Windows on the World restaurant on the 107th floor of the World Trade Center’s North Tower. Susana Genoves was on the building’s 78th floor when the plane struck and escaped by walking down 78 flights of stairs.

These artifacts number among the hundreds housed in NMAH’s National September 11 Collection. Through the new platform, users can easily browse the museum’s holdings, from a burned Blockbuster rental card recovered from the wreckage of Flight 93 to a Pentagon rescuer’s uniform.

The final component of the initiative is a story-gathering tool titled September 11: Stories of a Changed World. Per the museum statement, the portal “presents a yearlong opportunity for the public to share their memories … of that day, the days and years that followed and the lasting effects on their lives.” Prompts such as “How did you experience September 11” and “What object will always make you think of September 11?” offer participants a sense of where to begin their reminiscences. Users can submit their responses in English or Spanish, with up to five photos or one short video clip as supporting material.

“People don’t always think that 9/11—and it doesn’t matter what generation you’re in—had any direct effect on them,” says Yeh. “… What [we’re] trying to do here is help them understand that your stories still matter.”

The curator adds, “In gathering this information, we will not only be looking for new threads to follow or new potential collections, but also new collaborators. And hopefully, they’ll go hand in hand.”

Smithsonian American Art Museum

Ahead of the anniversary of 9/11, the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) published a blog post detailing five artworks inspired by or linked to the attacks. As writer Howard Kaplan explains, “[They] remind us of the moments of tragedy, the enduring spirit of a nation and the lasting impact of the events of 9/11.”

One of the selected artworks, Thomas Ruff’s jpeg de01 (2005), started out as a low-resolution photograph of debris at Ground Zero. Ruff enlarged the image to such an extent that it was rendered unrecognizable, “a patchwork of pixels that frustrates our attempt to see the image clearly and suggests the inconsistent nature of collective memory,” according to the museum.

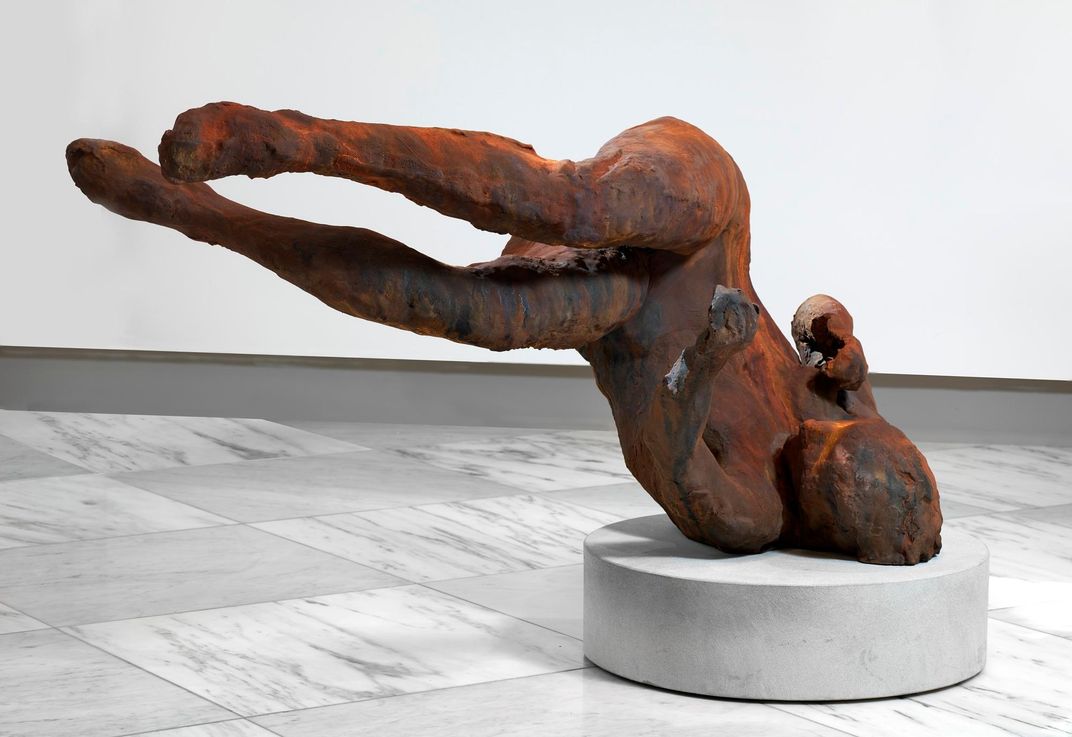

Another featured work, Erich Fischl’s Ten Breaths: Tumbling Woman II (2007–08), memorializes 9/11 victims with a bronze sculpture of a falling figure. Speaking at SAAM in 2014, Fischl said, “The experience of 9/11, the trauma and tragedy was amplified by the fact that there were no bodies. You had 3,000 people who died and no bodies, so the mourning process turned to the language of architecture.”

Read about the other artworks—Roy Lichtenstein’s Modern Head (1974/1990), Enrique Chagoya’s The Ghost of Liberty (2004) and Keivn Bubriski’s World Trade Center Series, New York City (2001)—here.

National Postal Museum

The National Postal Museum (NPM) houses an array of 9/11 artifacts in its collections. Objects tied to the tragedy include a handstamp from the mail sorting station on the fourth floor of Manhattan’s Church Street Station Post Office, a mail delivery cart used by letter carrier Robin Correta at World Trade Center Building 6 and a registry receipt recording the last transaction of the day at 8:47 a.m.

Educators seeking to teach students, many of whom have no firsthand memories of 9/11, about the attacks can draw on a new Learning Lab resource created by NPM intern Erika Wesch. Featuring a blend of text, images and videos, the digital collection focuses on the Church Street office, which exclusively served the World Trade Center’s Twin Towers. The office managed to evacuate all workers and customers by the time the South Tower fell, but as a photograph of a debris-covered room testifies, the building sustained a small amount of damage.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/57/1c/571c9877-8eb1-4904-ad8e-f0bc4647628a/screen_shot_2021-09-08_at_124306_pm.png)

In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, the Postal Inspection Service collected surviving mail and rerouted survivors’ correspondence to other post offices. (“[E]xtensively contaminated by asbestos, lead dust, fungi, fiberglass dust, mercury and bacteria,” the Church Street office remained closed for the next three years, as the New York Times reported in 2004.) The United States Postal Service also issued a stamp whose proceeds went to emergency workers. The stamp featured Tom Franklin’s now-iconic snapshot of three firefighters raising the flag at Ground Zero.

After revisiting 9/11 through the lens of this Manhattan post office, the Learning Lab lesson examines how the Postal Museum collected objects tied to the attacks. The resource concludes with a series of blog posts penned by curator Nancy Pope on the tenth anniversary of the tragedy.

“Decisions pertaining to … collecting materials from the Church Street Post Office were subject to intense debate within the museum in the weeks following the attack,” wrote Pope in 2011. “... The road to this point was often contentious, but one with lessons to share in confronting the collection and exhibition of difficult subject matter.”

National Portrait Gallery

The photographs, paintings, sculptures and artifacts on view in the National Portrait Gallery’s (NPG) “20th Century Americans: 2000 to Present” exhibition portray people at the center of major cultural and political moments of the past 21 years: entrepreneurs Bill and Melinda Gates, Oglala Lakota Sioux activist Russell Means, jazz bassist and singer Esperanza Spalding. But one object in the third-floor gallery defies easy categorization. Instead of depicting an individual, the twisted piece of steel is decidedly abstract—a poignant reminder of arguably the most defining event of the 2000s.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which owns the World Trade Center site, gifted the artifact—recovered from the wreckage at Ground Zero—to NPG in 2010. As the agency’s executive director, Chris Ward, said at the time, “Its presence at the Smithsonian Institution will serve as a powerful reminder of the unspeakable losses suffered that day and be a simple yet moving memorial.”

National Air and Space Museum

On September 11, 2001, Chris Browne, now acting director of the National Air and Space Museum, was employed as the airport manager of Ronald Reagan Washington National Airport (DCA). In a new blog post, he recounts the turmoil of that day, from securing the facility—“rental cars had been left idling at the curb, pizzas were still cooking, and unclaimed baggage continued in endless loop on the return carousels”—to closing its doors for the foreseeable future.

Though the rest of the nation’s airports reopened a few days after the attacks, DCA remained closed for almost a month. As Browne writes, he and his team viewed the removal of the fortified locks they’d had to install as “a sign of life renewed.”

The acting director adds:

As I reflect back on 9/11, twenty years after a day when time seemed to both slow down and speed up at the same time, the emotional toll of these attacks is even more stark. ... It’s still painful to grapple with: that commercial airliners, which I’d devoted my career to safeguarding the departure and arrival of, were turned into weapons; that technology that opened up our world was central to an act of terror that brought our country to a halt; that a craft that can bring so much joy brought about so much destruction.

Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center

Four days after 9/11, a gunman fatally shot Balbir Singh Sodhi, an Indian immigrant who owned a gas station and convenience store in Mesa, Arizona. Seeing Sodhi’s turban, the killer had assumed his victim was Muslim. In fact, the 52-year-old was a follower of the Sikh faith. Shortly before his death, he’d made a heartbreakingly prescient prediction about people’s inability to differentiate between Sikhs and Muslims, both of whom faced an uptick in hate crimes following the attacks.

A new video in the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center’s (APAC) “We Are Not a Stereotype” series discusses Sodhi’s murder as part of a broader conversation about Sikh Americans’ experiences. After 9/11, says host Vishavjit Singh, people who were “perceived to be ‘other,’” including Sikh, Muslim and Hindu Americans—or anyone with “brown skin” and “stereotypical features”—“bore the brunt of [the public’s] vulnerability [and] ignorance.” A cartoonist and educator, Singh created an illustration featuring some of the racist phrases hurled at him by strangers: terrorist, Taliban, towelhead and names laced with profanity.

“For me, the challenge was how do I respond to this, why are these people who don’t know me, who don’t know my story, … telling me to go back home?” Singh says. “I started using cartooning as a way to build bridges, to share my predicament and also figure out ways of telling the story of Sikh characters … because I know I don’t see myself represented in American stories.”

Another new video in APAC’s series centers on Muslim American experiences. Featuring a panel of Muslim American women, including artist and educator Alison Kysia and doctor Sabrina N’Diaye, the segment covers such topics as anti-Muslim bigotry and the power of storytelling as a tool for healing.

In addition to the “We Are Not a Stereotype” videos, APAC is publishing Q&As with featured speakers Kysia and Singh on its Learning Together portal.

“It is important to hear Muslims talk about what they love about their identity for a couple reasons, one being to counteract the barrage of negative stereotypes,” says Kysia. “There isn’t one experience of being Muslim, there are as many experiences as there are Muslims, so hearing Muslims articulate their love of their identity is a powerful antidote.”

:focal(297x182:298x183)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/c0/5c/c05c9ad4-4983-47f7-b314-7c1e356aeb3a/mobile_stairwell.jpg)

:focal(611x325:612x326)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/38/9f/389f1711-1d4d-4ac8-8956-1e40f80693fc/stairwell_social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/mellon.png)