The Complex Role Faith Played for Incarcerated Japanese-Americans During World War II

Smithsonian curator of religion Peter Manseau weighs in on a history that must be told

:focal(604x482:605x483)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2b/ec/2beccad6-382f-4f2e-a17f-60d88764af31/sc14_1b01f018n042.jpg)

When Yoshiko Hide Kishi was a small girl, her parents farmed Washington’s fertile Yakima Valley, where Japanese immigrants settled as early as the 1890s. At the time of her birth in January 1936, the Hides were well-established as an American farm family like so many others around the country. They grew melons, onions and potatoes, sustained by hard work and traditions passed down across generations.

Then life changed dramatically. In the aftermath of the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, authorizing the incarceration of more than 110,000 Americans of Japanese descent. The Hides lost their farm, and soon found themselves at the Heart Mountain War Relocation Center in northwest Wyoming, 800 miles from home.

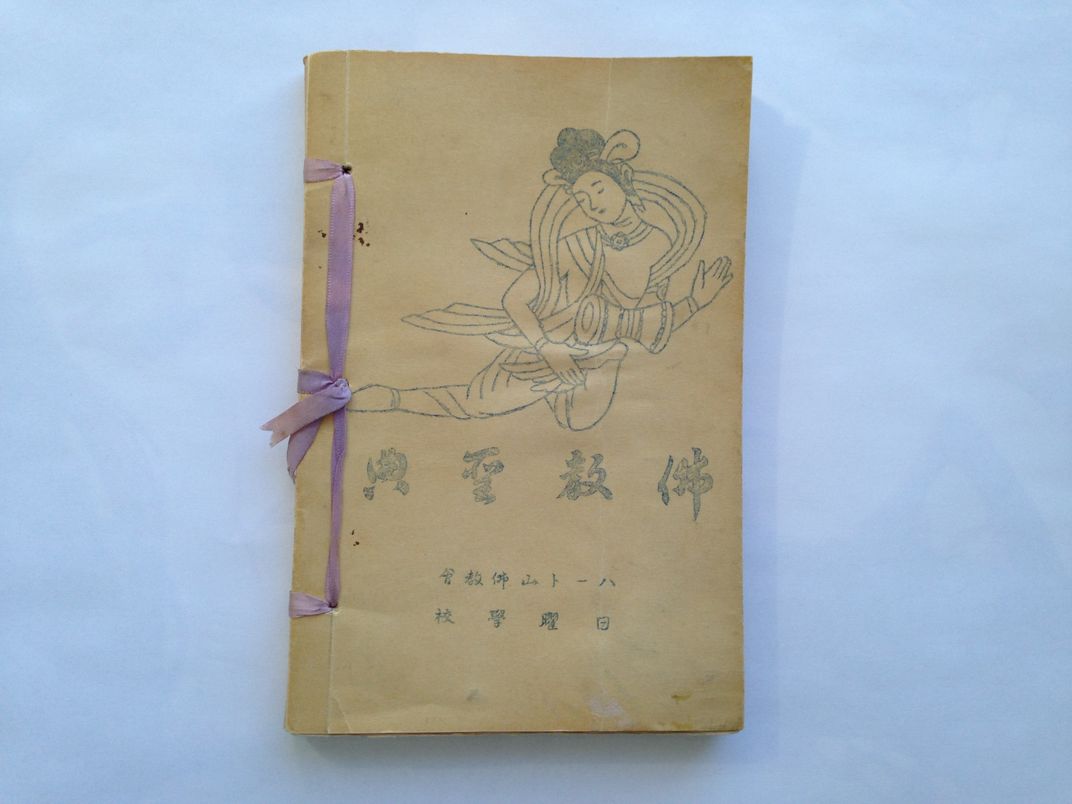

Faith was one of the few constants to be found in camp life. Like two-thirds of those incarcerated at Heart Mountain, the Hides were Buddhists. The young Yoshiko Hide attended religious education classes in a makeshift building referred to as the Buddhist Church, where she sang hymns in both Japanese and English that were published in a ribbon bound book of gathas, or poems about the Buddha and his teachings. Behind barbed wire fences erected by their own government, Hide and the other camp children—natural born citizens of the United States—recited words that today are a moving reminder of the way religion has been used to grapple with injustice:

Where shall we find the road to peace

where earthly strife and hatred cease?

O weary soul, that peace profound

In Buddha’s Holy Law is found.

And must we pray that we may find

The strength to break the chains and bind?

By each one must the race be run

And not by prayer is freedom won.

Following the war, Yoshiko Hide’s book of gathas from the Heart Mountain Buddhist Church remained hidden in a trunk for decades. After rediscovering it, she knew that she should share it with future generations. As she told Smithsonian curators as part of our efforts to collect the memories of survivors of this period in American history, “It is important to educate people about what happened to Japanese-Americans during the World War II incarceration, and especially to show that religions were able to share their teachings in English and Japanese.”

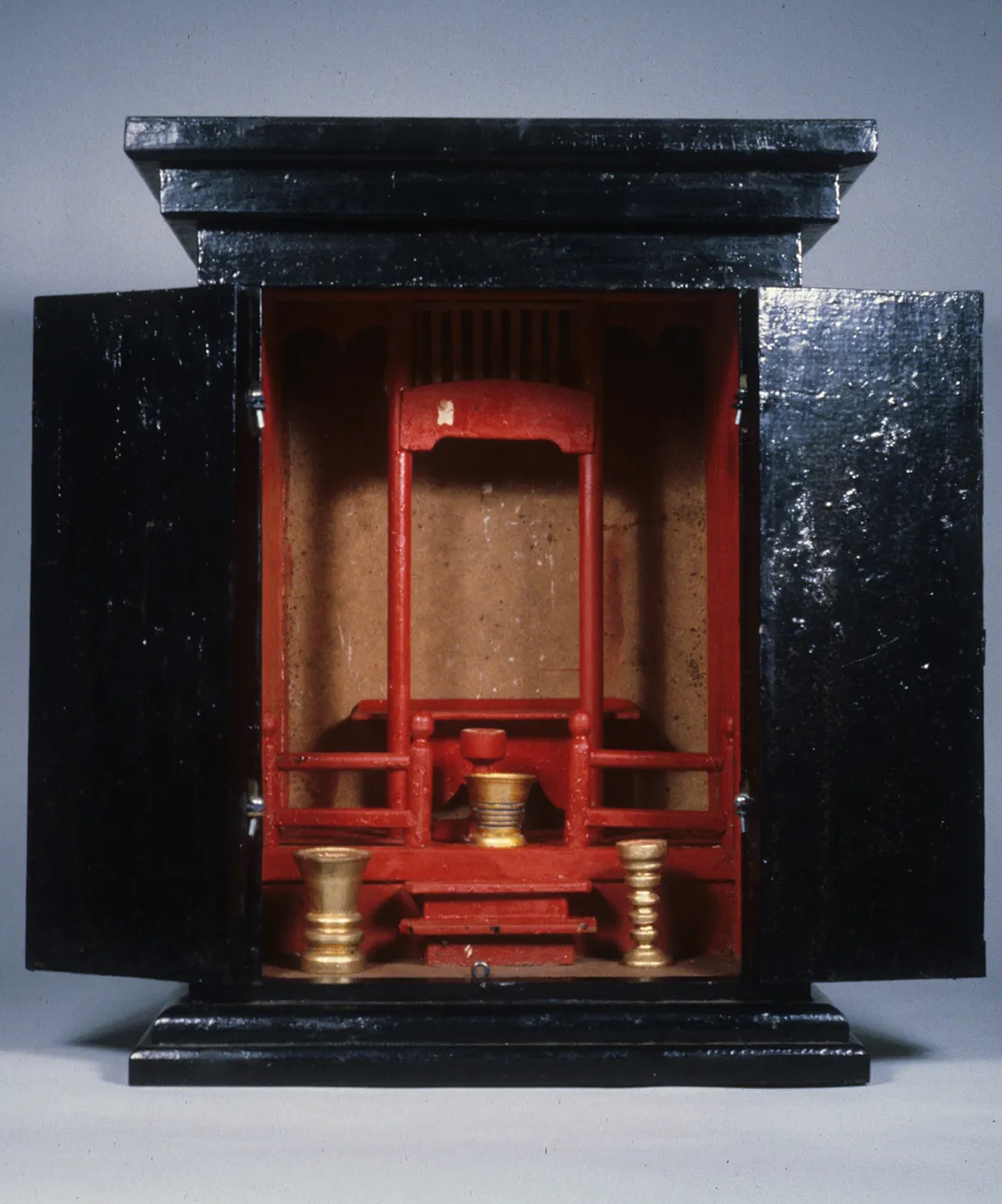

This poignant artifact reveals an important backstory about the improvised nature of religious life in the camps, one of thousands of stories that might be told to highlight a mostly forgotten aspect of the turbulent 1940s—the complex role faith played in the mass incarceration of Japanese-Americans. The collections of the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History include Buddhist altars made of scrapwood, thousand-stitch belts given for protection to Japanese-American soldiers going off to war, and Young Men’s Buddhist Association uniforms from camp athletic teams—all suggesting the ways both quotidian and profound that religious identity informed the incarceration experience.

Providing important new context for these objects and the much larger history of which they are a part, scholar Duncan Ryuken Williams’ new book American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War, explores for the first time the significance of religion, particularly Buddhism, among Japanese-Americans incarcerated at Heart Mountain and the nine other camps overseen by the War Relocation Authority.

“While it has become commonplace to view their wartime incarceration through the prism of race, the role that religion played in the evaluation of whether or not they could be considered fully American—and, indeed, the rationale for the legal exclusion of Asian immigrants before that—is no less significant,” Williams writes. “Their racial designation and national origin made it impossible for Japanese Americans to elide into whiteness. But the vast majority of them were also Buddhists. . . . The Asian origins of their religious faith meant that their place in America could not be easily captured by the notion of a Christian nation.”

This notion—that the United States is not merely a country with a Christian majority, but is a nation somehow essentially Christian in character—has served as the backdrop for many moments of religious bigotry throughout U.S. history, from widespread suspicion of the so-called “heathen Chinee” in the late 19th century, to dire warnings of a “Hindoo peril” early in the 20th century, to rampant Islamophobia in the 21st. Even before war with Japan was declared, Buddhists encountered similar mistrust.

Williams, director of the University of Southern California’s Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture, is both an ordained Buddhist priest and a Harvard-trained historian of religion. He has been gathering stories of the Japanese-American incarceration for 17 years, drawing from previously untranslated diaries and letters written in Japanese, camp newsletters and programs from religious services, and extensive new oral histories capturing voices that soon will be lost. The intimate view such sources often provide, he notes, “allow a telling of the story from the inside out, and make it possible for us to understand how the faith of these Buddhists gave them purpose and meaning at a time of loss, uncertainty, dislocation, and deep questioning of their place in the world.”

Before all that, however, outside perceptions of their faith shaped the experiences to come.

“Religious difference acted as a multiplier of suspiciousness,” Williams writes, “making it even more difficult for Japanese Americans to be perceived as anything other than perpetually foreign and potentially dangerous.”

This was not only a matter of popular prejudice, but official policy. In 1940, with the possibility of hostilities between the United States and Japan on the rise, the FBI developed a Custodial Detention List to identify potential collaborators with Japan living on U.S. soil. Using a classification system designating the supposed risk of individuals on an A-B-C scale, the FBI assigned an A-1 designation to Buddhist priests as those deserving greatest suspicion. Shinto priests were similarly classified, but as practitioners of a tradition explicitly tied to the Japanese homeland and its emperor, there were relatively few to be found in America. With ties to a large portion of the Japanese-American community, Buddhist priests became targets for surveillance in far greater numbers.

Deemed “dangerous enemy aliens,” the leaders of Buddhist temples throughout the coastal states and Hawaii were arrested in the early days of the war, a harbinger of the mass incarceration to come. The Rev. Nyogen Senzaki, for example, was 65 years old when the war began. Before he joined the Hide family and the nearly 14,000 others incarcerated at Heart Mountain between August 1942 to November 1945, he had spent four decades in California.

In a poem by Senzaki with which Williams opens the book, the self-described “homeless monk” recounts his time teaching Zen in Los Angeles as “meditating with all faces / from all parts of the world.” That he posed no threat to national security did not change his fate. His religious commitments, and the global connections they implied, made him dangerous in the eyes of the law.

Yet the role of Buddhism at this dark moment in the nation’s history was not simply to provide an additional category of difference through which Japanese-Americans might be seen. Religion in the camps served the same multifaceted purposes as it does everywhere. For many, the continuation of religious practice, whether occurring in public settings or privately in cramped family barracks, was an island of normality within the chaos of eviction and confinement.

Buddhists were known to dedicate a portion of their limited personal space to home-made altars, known as butsudan, so that they might continue to make ritual offerings. Despite the strain of additional scrutiny, Buddhist priests counseled those living in an impossible situation, and were often called upon to officiate funerals for those who would not see freedom again. For families like the Hides, bilingual Buddhist Sunday school classes offered an opportunity for children to remain connected to a language and a faith that were discouraged by many camp administrators as un-American.

Perhaps most significantly, Buddhist teachings, such as the benefits of meditation and the doctrine of reincarnation, which views every human lifetime as an opportunity to karmically advance to higher planes of existence, provided those affected by the incarceration both a framework through which to make sense of their experiences, and a goad to persevere.

“I have thought that this lengthy internment life has been provided to me by Heaven and the Buddhas as an opportunity for years or months of Buddhist practice,” one priest incarcerated at Camp Livingston in Louisiana wrote. “I have been viewing the guards’ searchlights as the Buddha’s sacred light.”

Less optimistically, and perhaps more representative of the desperation so many felt within the camps, one woman held at a temporary detention center at a racetrack outside Los Angeles wrote in her diary, “I must not give up. That would be against the will of the Buddha. As long as I was given the difficult birth as a human being, the use of my own hands to extinguish my life would be a major sin.”

American Sutra: A Story of Faith and Freedom in the Second World War

In this pathbreaking account, Duncan Ryūken Williams reveals how, even as they were stripped of their homes and imprisoned in camps, Japanese-American Buddhists launched one of the most inspiring defenses of religious freedom in our nation’s history, insisting that they could be both Buddhist and American.

Multiplied by tens of thousands of Japanese-American Buddhists, who similarly sought to apply traditional tenets to novel and trying circumstances, the result overtime, Williams suggests, was a transformation of the faith itself, the “birth of an American form of Buddhism.” In some ways, this new adaptation of an ancient faith was an accommodation to the same religious majority that felt threatened by it. In an effort to present itself as simply one denomination among many others in a nation crowded with sects, the organization formerly called the Buddhist Missions of North America first became known as the Buddhist Churches of America within the confines of Utah’s Topaz War Relocation Center. Yet such accommodations, while seeming to some to conform too closely to Christian expectations, also served to further a new insistence that Buddhism, like any other faith, could be central to American identity.

As American Sutra relates, the story of Buddhism in the United States during World War II should not be of interest solely to the families of those incarcerated. It is, instead, a searingly instructive story about America from which all Americans might learn.

Just as Jewish and Christian religious metaphors, from “promised land” to “the city upon a hill,” have become entwined with national self-understanding—Buddhism, too, might offer a view of the nation’s spirit that is at once useful, poetic and true.

“The Buddha taught that identity is neither permanent nor disconnected from the realities of other identities,” Williams writes. “From this vantage point, America is a nation that is always dynamically evolving—a nation of becoming, its composition and character constantly transformed by migrations from many corners of the world, its promise made manifest not by an assertion of a singular or supremacist racial and religious identity, but by the recognition of the interconnected realities of a complex of peoples, cultures and religions that enrich everyone.”

Such an interpretation of the American past and present may yet help provide that most elusive of lessons where history is concerned: the wisdom not to relive it.

The National Museum of American History will commemorate Day of Remembrance on February 19, 6:30-8 p.m., with a lecture by Duncan Ryuken Williams, a performance by the award-winning singer-songwriter Kishi Bashi, and a conversation with Smithsonian curators about memory, faith, and music during the Japanese-American incarceration. The museum's exhibition "Righting a Wrong: Japanese Americans and World War II" is on view through March 5, 2019.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/PManseau.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/PManseau.jpg)