The Complicated Relationship Between Latinos and the Los Angeles Dodgers

A new Smithsonian book and an upcoming exhibition, ‘¡Pleibol!,’ recounts the singular importance of baseball in Latino history and culture

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/00/8100bfbe-dc96-4dab-ab69-b26f6ec7d811/14331193150_c4e027c1c5_k.jpg)

Since the 1970s, Los Desterrados, meaning “The Uprooted,” have annually convened at their childhood stomping grounds right outside of the gates of Los Angeles’ Dodger Stadium. These reunions are an opportunity for families to reminisce about the old neighborhood—these are the communities of Palo Verde, La Loma and Bishop—together known as Chavez Ravine.

The families had moved into the area in the 1910s during a time when restrictive housing covenants prevented Mexicans from living elsewhere in the city. Soon, however, with stores, a school, a church and salon, they created a self-sufficient community.

¡Pleibol! En los barrios y las grandes ligas

The extraordinary stories of Latinas and Latinos, alongside the artifacts of their remarkable lives, demonstrate the historic role baseball has played as a social and cultural force within Latino communities across the nation for over a century and how Latinos in particular have influenced and changed the game.

And by the 1950s, the people of the three established neighborhoods enjoyed a vibrant community life that included fiestas and parades. Desterrados board member Alfred Zepeda remembers having three cultures:

We had the Mexican culture that our parents brought to us from Mexico, and we spoke Spanish at home and things like that. We would go outside out in the neighborhood where we would gather with the guys, and it was a Chicano culture, which was different. They spoke half Spanish, half English and, you know, the music was rock n’ roll and rhythm and blues and stuff like that. And then we walked a mile or two miles down, and then we were in the American culture. Everything would change, and we would go into a different world.

Today, they gather outside Dodger Stadium, because their homes and community are now buried beneath it. Before their neighborhoods were flattened to make way for Dodger Stadium, Mexican American youth roamed the hills of Chavez Ravine and spent their days playing games, including baseball.

It was during the summer of 1950, when nearly 1,100 families of Chavez Ravine received notice from the Los Angeles Housing Authority that their homes would be torn down for the construction of a public housing project. The city had designated their neighborhoods as “blighted,” a term used most often to condemn areas predominantly occupied by racial and ethnic minorities. When residents organized and resisted, the city of Los Angeles invoked eminent domain against them, allowing the seizure of private property for public use.

But shortly afterwards, the city scrapped the housing project, and in 1957, it negotiated a deal with the Los Angeles Dodgers to build a modern concrete stadium in Chavez Ravine at the edge of downtown Los Angeles.

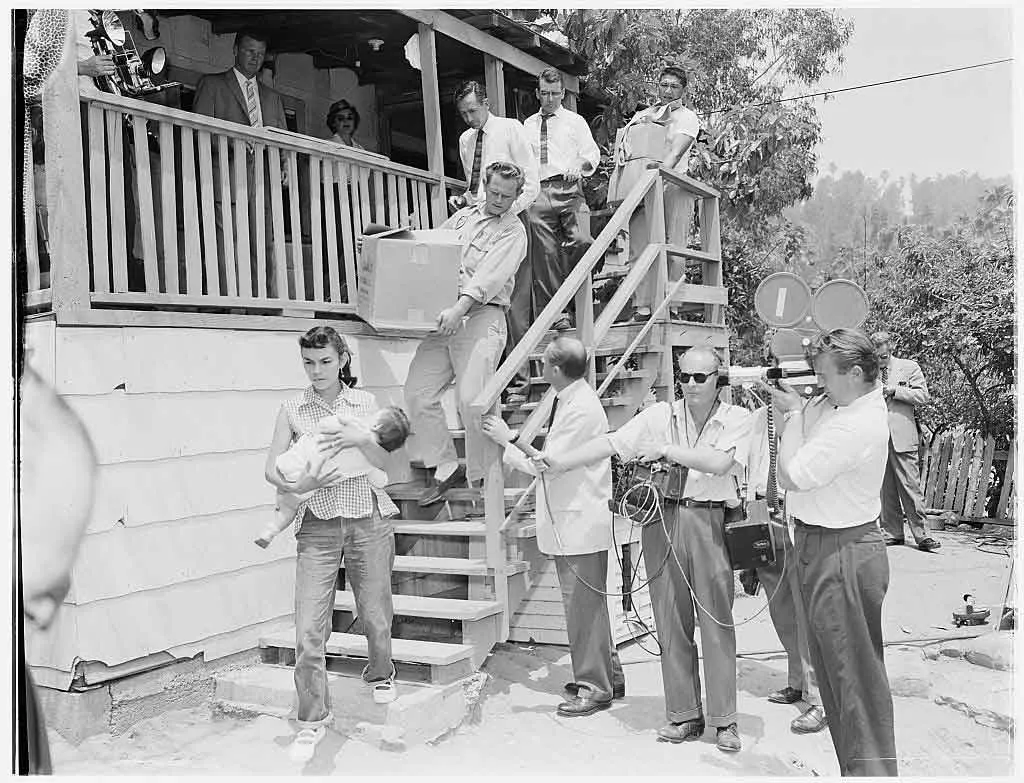

Two years later and a few months before the Los Angeles Dodgers broke ground for their stadium, Los Angeles sheriff’s deputies came to the home of one family, the Arechigas, to forcibly evict them. Television crews arrived and the two-hour melee was broadcasted across the nation. In one shocking scene, sheriffs carried Aurora Vargas out of her home against her will, reopening the deep wounds of racism that for some residents have reverberated over the decades.

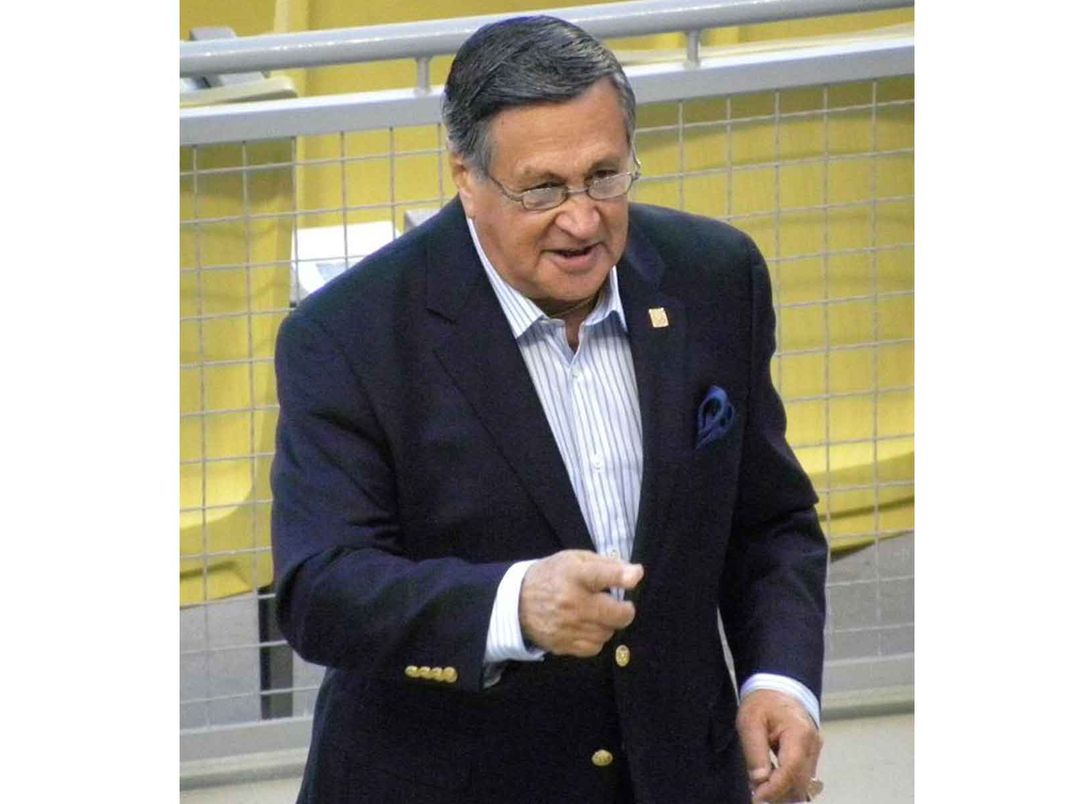

Even as displaced residents were working to rebuild their lives, the Dodgers began courting Latino and Latina fans. In 1959, the team became the first to broadcast their games on the radio in Spanish, hiring Ecuadorian Jaime Jarrín as the team’s radio announcer.

Jarrín’s broadcasts brought the game into Latino homes throughout Southern California and northern Mexico; his dramatic play-by-play narrated every pivotal moment. By 1970, Jarrín had become the first Latino to win the industry’s prestigious Golden Mic Award, and in 2018 he was inducted into the Ring of Honor at Dodger Stadium.

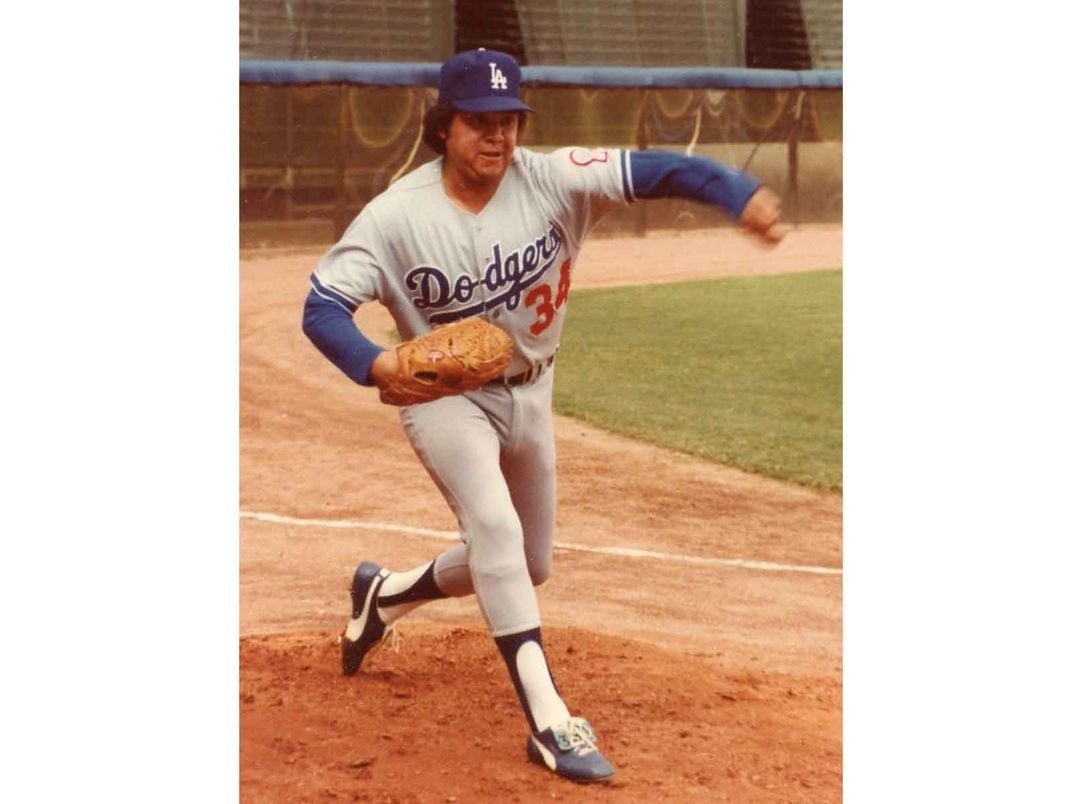

Complementing Jarrín’s popularity was the meteoric rise of Fernando Valenzuela, a left-handed pitcher from the rural town of Etchohuaquila in Sonora, Mexico, who also won the hearts of Latina and Latino audiences.

When Valenzuela took the mound on opening day in 1981, he caught the nation by surprise with his signature screwball pitch—which he’d learned from his Mexican American teammate Bobby Castillo—to win in a shutout against the defending division champions the Houston Astros. Valenzuela would go on to win his next seven starts. He had arrived as an unknown immigrant on the team, but he would dominate the game, inspiring LA’s Latino audiences, who represented 27 percent of county’s population.

Hanging on to announcer Jarrín’s every word, they soon began calling their team “Los Doyers.”

No one could have predicted Valenzuela’s popularity and with the steady rise of “Fernandomania” creating pride, droves of Latinas and Latinos—including some of the children of Los Desterrados—came to the stadium to witness the ascension of someone like them to greatness.

According to Jaime Jarrín, only eight to ten percent of the audience at Dodger Stadium were Latino before Valenzuela took the mound. Fernandomania changed the face of the stadium for decades to come. Together, Valenzuela and Jarrín transformed Latinos into Dodgers fans, and by 2015, 2.1 million of the 3.9 million fans attending Dodger games were Latino.

These layered histories have made Chavez Ravine a central site of Latino life across the region—a site of injustice that demands reflection, and in a space where they fought for pride and dignity long before the Dodgers moved west.

This essay by Priscilla Leiva, an assistant professor of Chicana/o and Latina/o Studies at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, was adapted from ¡Pleibol! In the Barrios and the Big Leagues / En los barrios y las grandes ligas by Margaret N. Salazar-Porzio and Adrian Burgos Jr. Leiva has served as advisor to the Smithsonian’s upcoming exhibition, opening April 1, 2021 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.