Behind This Photo Is the Story of Two Asian American Folk Heroes

Corky Lee’s photograph of Yuri Kochiyama captures the familiar struggle of those living at the margins of society

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9a/fc/9afc8c29-9910-4ad8-868e-ac3741db4ac3/untitled-2.jpg)

One of the most iconic images of Yuri Kochiyama shows the young political activist cradling the head of her friend, Malcolm X, as he lay dying after being gunned down by assassins. This memorable scene reflects only a moment in the decades-long civic activism of this driven, passionate hero and champion of the dispossessed. Kochiyama would spend her entire adult life working tirelessly to protect the rights of all Americans living at the margins of society.

As a survivor of the U.S. camps that held Japanese nationals and Japanese Americans in incarceration camps during World War II, she formed the foundations of her life’s work to reach out to anyone she felt was being crushed by the white majority. She helped Puerto Ricans seeking independence, African Americans struggling to find equality, and many others, placing no borders on her willingness to fight the good fight. Yuri Kochiyama would have been 100 years old on May 21, in a month dedicated to Asian Pacific American Heritage.

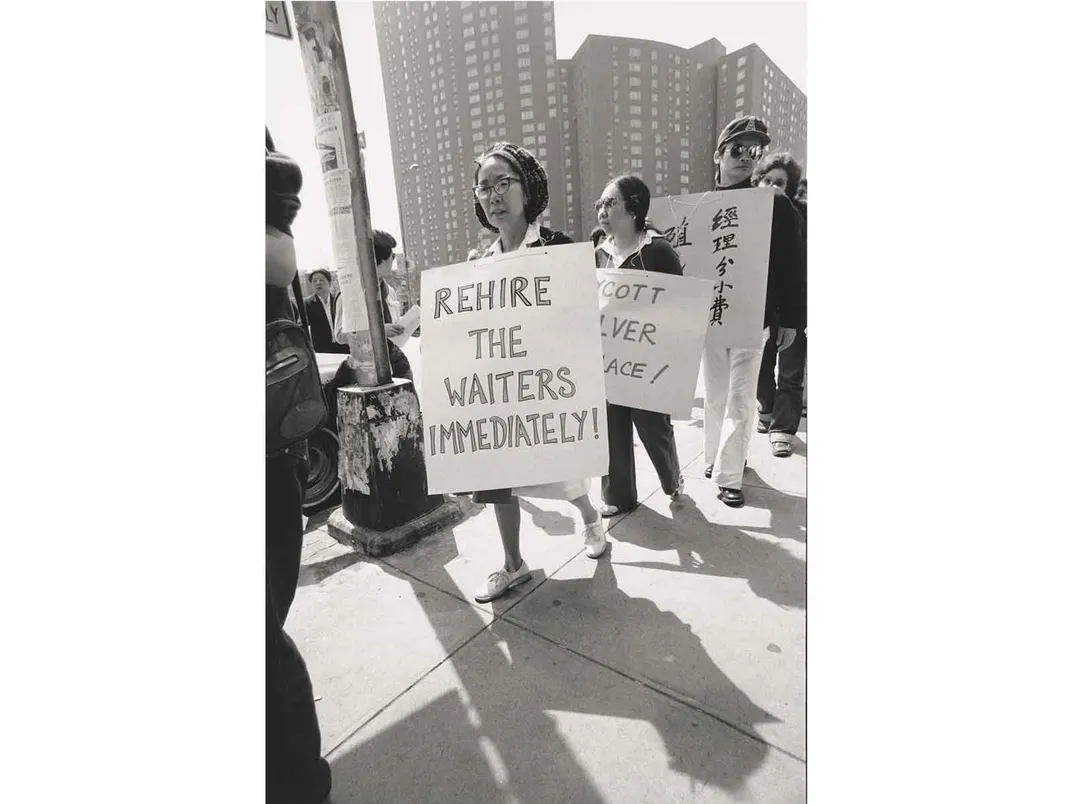

The Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery holds another meaningful photograph of Kochiyama marching in the streets of New York City’s Chinatown neighborhood to defend the rights of Silver Palace restaurant workers who had lost their jobs after refusing to share a higher percentage of their tips with the restaurant’s owners. With Kochiyama’s help, the staff won their fight and regained their jobs. Photographer Corky Lee, who worked throughout his life to capture important moments in the lives of Asian Americans, took the photo in 1980, when Kochiyama was in her late 50s.

“It’s that perfect combination of subject and artist. You have someone behind the camera who cares passionately about documenting the Asian American experience and giving presence to a community that was so often either overlooked or maligned. And you have an activist subject with Yuri Kochiyama, who did not limit her activism to causes related to her Asian American experience, but also connected with Malcolm X and with the Young Lords organization, the Latinx activist group in New York. It’s the perfect visual document for the museum’s collection,” says Smithsonian senior curator Ann Shumard.

Kochiyama grew up in California. After the 1941 Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, which drew the United States into World War II, her ill father was arrested and held for several weeks. He died the day after his release. As a young Japanese-American woman, she spent years in what the U.S. government called “an internment camp,” but what she called “a concentration camp.” Most of her incarceration occurred at the Jerome Relocation Center in Arkansas. There, she met her husband, Bill, a member of the U.S. military fighting in the all-Japanese-American 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

They married shortly after the end of the war and moved to New York City. During their marriage, the pair pushed for federal legislation that offered reparations to those incarcerated during the war. The Civil Liberties Act, a part of which offered a formal apology to Japanese Americans and Japanese nationals, granted $20,000 to each internee; the bill was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan in 1988. At one point in their lives, the Kochiyamas revisited the site of the camp, and that trip into the past served as a chapter in My America . . . or Honk If You Love Buddha, the 1997 documentary produced by Renee Tajima-Peña, creator of last year’s popular PBS show “Asian Americans.”

Over the years, Kochiyama became involved in a wide variety of social movements, always in an effort to help oppressed individuals and groups. When she died in 2014 at 93, Adriel Luis, the curator of digital and emerging media at the Smithsonian’s Asian Pacific American Center, created "Folk Hero: Remembering Yuri Kochiyama through Grassroots Art," an online exhibition to celebrate her life.

“A folk hero is somebody whose legacy is carried on from a grounded community level, even in the absence of institutional recognition,” says Luis, who was surprised that he had so much difficulty finding representations of Kochiyama from larger media and official sources. He gathered most of the artwork in the exhibition through personal outreach to members of the Asian American community.

He recalls that years before, as an Asian American studies student at University of California, Davis, he considered Kochiyama “as a civil rights icon who was just always someone who has been present in my understanding of the world, in my understanding of community and culture—up there with Martin Luther King Jr and Malcolm X.”

“Asian American activism, as we know it,” he says, “is something that took some time to catch up to who Kochiyama was and the kind of leadership that she exhibited.”

Given the unrest of the last year, Luis argues that “a lot more institutions and companies are feeling ready to speak out in favor of social issues that they may not have touched on before. And people like Yuri and Malcolm are being revisited and being appreciated in new ways.” Kochiyama conveyed a sense of the connections between different groups who faced systems intended to suppress and abuse them. Her causes were both national and international, and she played a significant role in the fight for African American civil rights. Luis notes that Kochiyama’s connection to Malcolm X at the time of his assassination unfortunately was erased in Spike Lee’s Malcolm X, which depicts Malcolm dying in his wife’s arms.

Though her name may not carry the recognition given to Martin Luther King Jr., Kochiyama is not unknown. “The notion of a Folk Hero often emerges from the blurring of fact and fiction; America is full of these figures,” writes Luis in the exhibition. “Their lives are kept alive through stories and songs, performance and art, on the tongues of those who believe in the richness of preserving their legacies.”

And just like other folk heroes, Kochiyama is remembered in diverse parts of popular culture. She is the subject of a play, Yuri and Malcolm X, written by Japanese-American playwright Tim Toyama, who said, “The Malcolm X Movement was probably the last thing you would imagine a Japanese American person, especially a woman, to be involved in.” The two radicals met after Kochiyama and her eldest son were arrested with hundreds of Black protesters during an October 1963 demonstration in Brooklyn. Malcolm X entered the courthouse and was immediately surrounded by African American activists. Initially hesitant to press for attention from an African American leader, Kochiyama caught his attention and asked to shake his hand. The friendship that followed included exchanges of postcards. The two shared a birthday, though Kochiyama was four years older.

Furthermore, she is featured in “Yuri,” a hip-hop song recorded by the Blue Scholars. One of the Seattle-based band’s vocalists, Prometheus Brown, is a Filipino-American and activist. The group’s 2011 album, Cinemetropolis, aimed to celebrate those who have led Asian Americans and drawn connections among them. The song repeats this message: “When I grow up, I want to be just like Yuri Kochiyama.”

Corky Lee was also a role model in Asian American communities. He “was determined both to restore the contributions of Asian Americans to the historical record and to document their present-day lives and struggles, especially those living in New York,” wrote Neil Genzlinger of the New York Times when Lee died January 27, 2021, from Covid-19. The son of Chinese immigrants, Lee also tried to capture evidence of unfair treatment of Asians. “For over four decades, Lee ensured that Asian American resistance to the Vietnam War in the ’70s, Vincent Chin’s murder in the ’80s, anti-Indian American violence in the ’90s, Islamophobia post 9/11, and the racism that surged with the COVID-19 pandemic would be embedded in public memory,” Luis wrote in an appreciation, following Lee’s death.

Lee’s body of work, says Luis, “gives us clarity of what we mean when we talk about this multitude of people that encompass Asian Americans.” He sees the photographer as “a connective tissue for our community and his photos are living proof of the fact that this coalition that we know as Asian Americans has been something in the works for decades.”

One of his most memorable projects was a response to the well-known photograph taken in 1869 that showed the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad. Lee noticed that not one of the estimated 15,000 Chinese workers who helped to build the nation’s railroad lines is seen in the photograph. Consequently, he gathered Chinese Americans, including descendants of the workers who built the railroad, and recreated the scene, correcting perceptions of a moment in history.

Luis believes that it is important to remember both Kochiyama and Lee for what they accomplished in the public sphere, but also to recall the little things that colored their individual lives outside the spotlight, such as Kochiyama’s love of teddy bears and Lee’s often lovably curmudgeon-like behavior.

The National Portrait Gallery recently reopened Wednesday through Sunday, 11:30 to 7 p.m., following a six-month closure due to Covid-19. The Smithsonian’s Asian Pacific American Center’s exhibition “Folk Hero: Remembering Yuri Kochiyama through Grassroots Art” is available online. Smithsonian visitors must acquire free, timed-entry passes in advance.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)