Coyotes Poised to Infiltrate South America

The crab-eating fox and the coyote may soon swap territories, initiating the first American cross-continental exchange in more than three million years

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0a/9c/0a9c2a0e-ae01-46e6-9a8b-3bb959abab4c/5711528512_3140ec84ab_o.jpg)

For 10,000 years—and possibly many more—the borders of the coyote’s wild empire more or less stayed put. Penned in by the dense forests where their wolf and cougar predators tended to roam, these cunning canines kept mostly to the dry, open lands of North America’s west, scampering as far north as the alpines of Alberta and as far south as Mexico and bits of the Central American coast.

Then, around the turn of the 20th century, nature’s barriers began to crumble. Forests began to fragment, wolf populations were culled, and coyotes (Canis latrans) began to expand into regions they’d never been before. By the 1920s, they’d found their way into Alaska; by the 1940s, they’d colonized Quebec. Within a few more decades, they’d tumbled across the Eastern seaboard and trickled down into Costa Rica, all the while infiltrating parks, urban alleys and even backyards.

“Coyotes are flexible and adaptive,” says Roland Kays, a zoologist at North Carolina State University, the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences and with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. “They’re such good dispersers, and they’re able to deal with humans. This is one of the few species that’s been a winner in the Anthropocene.”

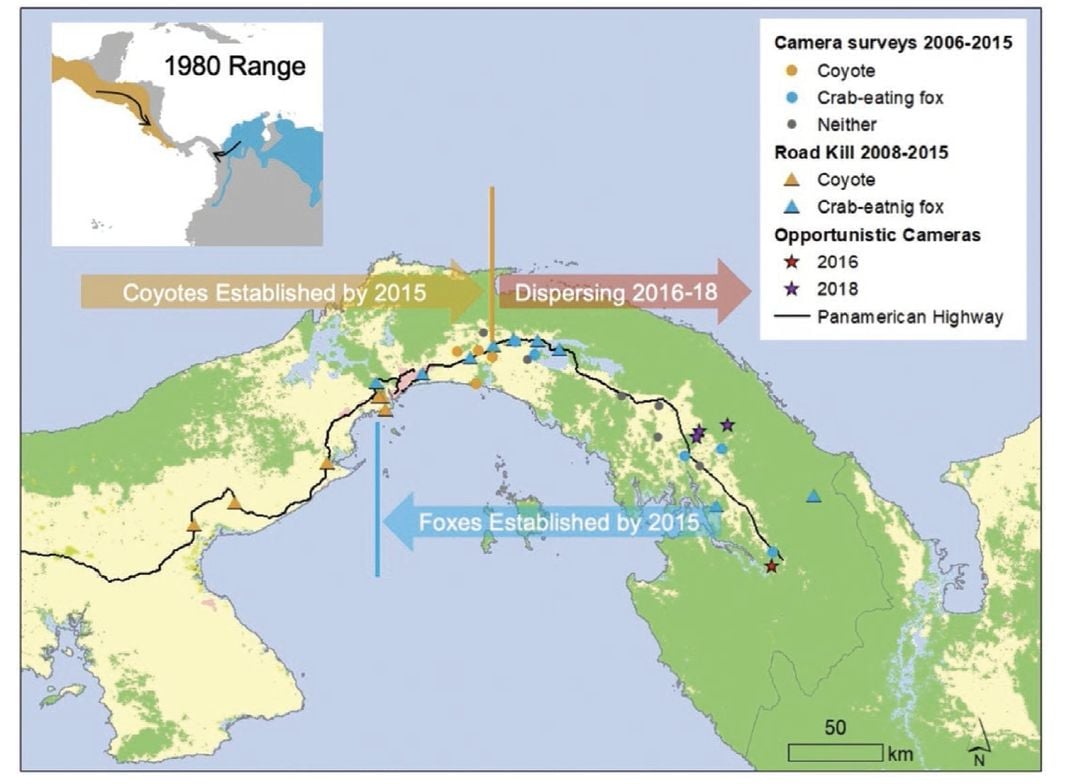

Now, coyotes stand at the doorstep of South America, poised to penetrate an entirely new continent—one they’ve never naturally inhabited before. Kays’ latest study, published recently in the Journal of Mammalogy, shows they’ve made their first forays into Panama’s Darién National Park, a ferociously forested landscape teeming with jungles and jaguars, and the last obstacle standing between the coyotes and Colombia.

If and when coyotes cross over, “I wouldn’t be surprised if they colonize all of South America,” Kays says. Should they spread this far, the canids could become one of the most widespread land animals in the western hemisphere, exposing a whole host of species to a new and unfamiliar predator. The Darién is “one more barrier that could slow coyotes down,” Kays adds. “But it probably won’t.”

In just under a century, the coyote conquered the North American continent. The species can now be found in every U.S. state except Hawaii, and can be found prowling habitats from parks and playgrounds to urban alleys and fenced backyards, where they’ll feast on just about any food they scrounge up. There’s little doubt that this wayfaring feat has been helped along by human hands: Surges in deforestation and the killing of wolves, cougars and jaguars have effective cleared the way for the canids to roam farther and wider than they ever have before. But in large part, coyotes have expanded on their own, says Megan Draheim, a conservation biologist at Virginia Tech and founder of The District Coyote Project who wasn’t involved in the study. Rather than hitching rides on ships or planes like some other species, these plucky pilgrims have simply “taken advantage of the changes to the landscape people have made,” she says.

Camera traps set by Kays and his colleagues show that history is now repeating itself in Panama, where deforestation and development continue to trim the region’s tree cover. Combined with the region’s species records, thousands of camera-trap images captured in the last 15 years show that, with each passing year, coyotes are pushing their way into territory they’ve never trod through before. In the three years following 2015, they expanded their range by at least 120 miles—a faster pace than the average rates they’ve clocked in up north.

And our southern continental neighbor is already sending another species back our way: the crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous), another hardy, opportunistic canid that Kays calls the “coyote of South America.” Native to the continent’s savannas and woodlands, this dog-sized carnivore scampered into Panama for the first time in the late 1990s, and has continued its northerly campaign ever since.

Converging on the Central America corridor from opposite directions, the coyote and the crab-eating fox now share habitat for the first time in recorded history. Should both press on at their current rates, the two species will soon trickle into each other’s original territories, executing a cross-continental predator swap that hasn’t happened in the Americas in at least three million years.

Exchange in and of itself isn’t a bad thing, Kays says. The world’s species are constantly growing, evolving and migrating. But he points out that the troubling part of this trend isn’t necessarily the switcheroo itself, but the circumstances surrounding it.

A big part of what’s kept the coyotes and the crab-eating foxes in their respective ranges has been the robustness of Central American tropical forests and their rich menagerie of species, including jaguars and cougars that like to nosh on mid-size canids. As these arboreal habitats disappear, the creatures that call them home are blipping out alongside them—and inadvertently paving a path for new, foreign predators to take their place. In a way, the expansion of coyotes and crab-eating foxes has become a symptom of the western hemisphere’s faltering biodiversity.

Forecasting what will happen next is difficult. Much of the Darién and its wildlife remain intact, and conservationists are working hard to ensure it stays that way. Even if the forest is an imperfect barrier, Kays says, perhaps it can still be an excellent filter: Camera traps have so far only noted two coyotes in the region, including one injured, perhaps by a rough-and-tumble rendezvous with a jaguar.

Several more years may pass before coyotes enter Colombia—and even when they do, a few stray interlopers does not a stable population make. “If one coyote shows up, they’re not going to have anything to breed with,” Kays says. (Though he also notes that coyotes can couple up with other canids like wolves and dogs, which may already be happening in Panama.)

But in all likelihood, where the coyote can go, it will, says Eugenia Bragina, a wildlife conservationist at the Wildlife Conservation Society. And the consequences could go either way. While some South American prey species, both wild and domestic, may not take kindly to tussling with a new predator, visits from coyotes aren’t always unwelcome, and the canids can even help keep pest populations in check.

And in this human-dominated era, which has been largely unkind to the world’s bigger-bodied mammals, “it’s nice to see a carnivore success story,” says Julie Young, a carnivore ecologist at the USDA who wasn’t involved in the study. Despite a multitude of human efforts to curb their numbers, including lethal control, the coyotes haven’t just held their ground. They’ve thrived.

In a way, the coyote trajectory runs parallel to our own, Kays says. Like humans, coyotes are wily and versatile, out to explore the edges of their map. “So let’s see what we can learn from them,” he says. “Maybe the fast adaptability of the coyote gives us hope that other species, with a little more protection, can find ways to survive on this planet as well.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/10172852_10152012979290896_320129237_n.jpg)