This Culture, Once Believed Extinct, Is Flourishing

A new exhibition explores the cultural heritage of the Taíno, the indigenous people of the Caribbean

:focal(1088x522:1089x523)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/8d/53/8d534c2e-5911-465d-b0dc-38ccaea186d1/pic_6.jpg)

How does one celebrate a living, even thriving, heritage when the world thinks it disappeared hundreds of years ago? That is one of the questions asked by “Taíno: Native Heritage and Identity in the Caribbean,” a new exhibition co-produced by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and the Smithsonian Latino Center. On view at the museum’s George Gustav Heye Center in New York City, the show explores the legacy of the indigenous peoples of the Caribbean (known as the Taíno people) and how this Native culture, which stems from the Arawak-speaking people of Cuba, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Haiti and the Dominican Republic, has persevered and grown in influence—despite a mistaken belief that it is extinct.

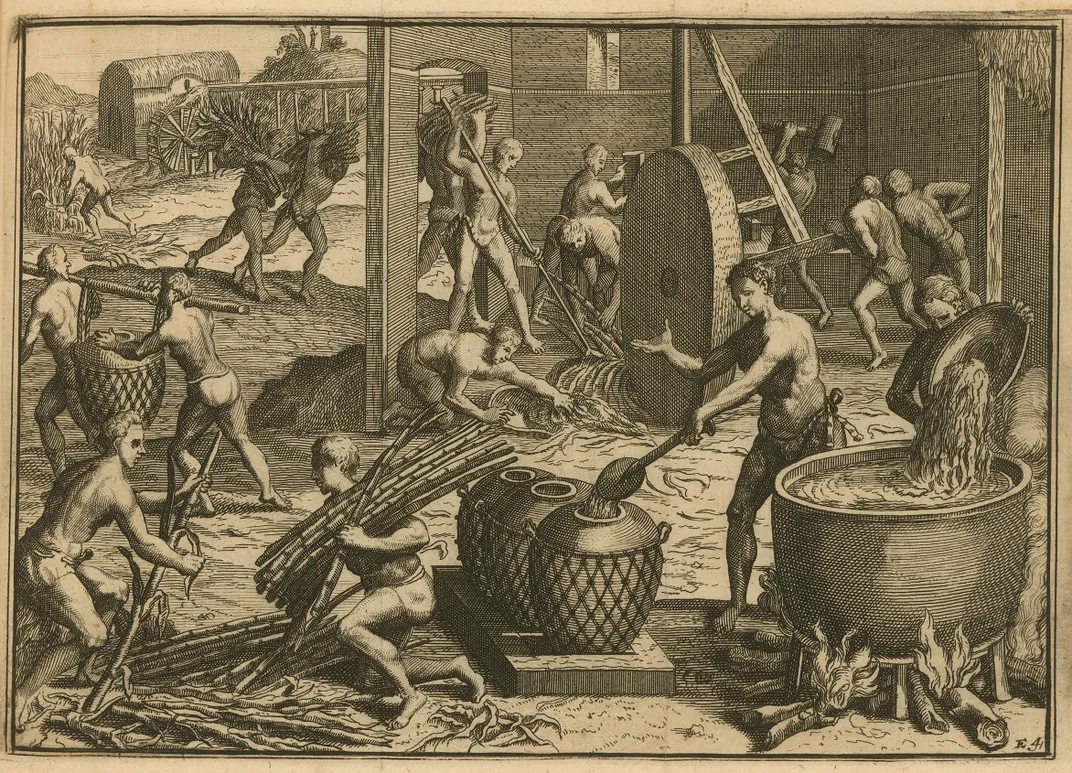

It’s a story of survival in the face of long odds. The arrival of Europeans to the Caribbean, beginning with Christopher Columbus in 1492, brought foreign diseases, enslavement, conquest and disruption to the indigenous people’s agrarian lifestyle. This moment of contact proved devastating, leading to the loss of 90 percent of the Native people.

But while this destruction is the inciting incident of the exhibition, it’s the surviving 10 percent of the people who are its focus. According to curator Ranald Woodaman, the Smithsonian Latino Center's exhibitions and public programs director, the show is about “the living legacy” of Native peoples in the Spanish-speaking Caribbean, in the Greater Antilles and on the U.S. mainland. He says that the show digs deeply into how the surviving 10 percent maintained and adapted their traditions, and how activism and Taíno identity developed into the current Taíno movement. The United Confederation of Taíno Peoples is an active participant of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues.

“In the last 20 years, a lot of Caribbean folks have said, ‘where’d this movement come from? History books tell me the opposite,’ and yet everybody who is Native has family stories and connections,” says Woodaman. “This is a complicated story because in many ways we are reframing histories like survival and extinction. We’re saying that we can survive through mixture and change.” Many Taínos, today, are ethnically mixed descendants of not only Native peoples, but Africans and Europeans.

The exhibition explores how survival tactics included the surfacing and passing down of Native knowledge. One prominent example is what the show calls the “Native Survival Kit:” The traditional house known as a bohío, constructed with plants or vines or other local materials resistant to weather; and the conuco, the traditional garden plot. In the early 1900s, these traditional practices helped rural Cuban, Dominican and Puerto Rican communities with limited funds to be able to build their own homes and produce their own food.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/19/4b/194b9d0e-0184-4efe-bf4e-a392dbaced3d/pic_4.jpg)

Another example is casabe, a flatbread made from yucca or cassava flour. Certain types of yucca may be poisonous—but when prepared right do not spoil (a valuable trait in the Caribbean heat, where wheat breads made by the Spaniards would quickly go bad). Understanding how to prepare casabe, and even how to use the extracted poison to help catch fish, meant the difference between life and death.

The term Taíno began to be used in the early 1800s, and its meaning shifted over time. Today, it has been embraced by people of Native ancestry as a term that unites a wide range of historic experiences and identities. “It’s an overall term that brings a lot of people of Indian ancestry, Native ancestry, together in the present moment,” says Woodaman.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/87/b48703e2-b8fd-4fa2-9d48-d520382a5cb6/pic_1.jpg)

This sense of a common identity and efforts to preserve or celebrate it became more pronounced starting in the 1970s, as groups around the country sought to “highlight and make this legacy visible, but around different agendas and purposes,” as Woodaman puts it. In Pittsburgh, the Caney Indian Spiritual Circle, focused on spirituality and healing, was established in 1982. In the tristate area of New York, the Arawak Mountain Singers formed in 1991 and grew active in the powwow circuit during that time. More recently, the yukayeke, or village, of Ya’Ya’ Guaili Ara formed in the Bronx, dedicated to preserving, recovering and sharing its members’ Native heritage. Each community focused on different areas of Taíno culture, but had much in common at the same time.

These efforts include language research—trying to reconstruct ancient linguistic traditions or explore the Taíno roots of familiar words (terms such as hurricane, hammock and tobacco have been credited to Taíno)—as well as environmental and public policy efforts.

The exhibition touches on how the growing popularity of DNA testing fits into all of this. “It indicates that there were larger populations of Native people who survived for a longer amount of time in the colonial period, for this genetic material to be so widespread,” says Woodaman. But he discourages using the DNA testing as a way for individuals to attempt to determine exact percentages of ancestry, adding: “That is not what identity is.”

While the exhibition focuses on the centuries-long perseverance of the Taíno people, it also features ancestral objects and artifacts that help to define the culture prior to colonization. Nearly 20 of the artifacts date from A.D. 800 to 1500, before European contact. Items from Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic and Cuba are in the show, such as cemís—stone, wooden or cotton artifacts used in spiritual ceremonies—wooden seats made for a political leader, or conch shells on which the face of a person has been carved.

The origins of this exhibition began in 2008, when researchers identified a small trove of Taíno artifacts in the Smithsonian’s collections that they wanted to bring to light.

“We thought, here we have the components for a really interesting exhibit that goes beyond Columbus and brings it to the present,” says Woodaman. “It took a while to come to terms with how to make the most powerful, timely and relevant exhibit we could.”

“Taíno: Native Heritage and Identity in the Caribbean,” curated by Ranald Woodaman with contributions from José Barreiro and Jorge Estevez, is on view in New York City at the National Museum of the American Indian’s George Gustav Heye Center, One Bowling Green in lower Manhattan through October 2019. On Saturday, September 8, the museum presents: “Taino: A Symposium in Conversation with the Movement ” from 10 to 5:30.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)