Curator Talk at the American Art Museum on African-American Art Exhibition

Virginia Mecklenburg offers a Wednesday lecture on the artists from “Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era and Beyond”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20120731114010lawrence_bar_and_grill_thumbnail.jpg)

In black and white, she sits reclined between the knees of an older woman. Her hair is half braided, her eyes glance sideways toward the camera. The image, on display at the American Art Museum, is a moment in photographer Tony Gleaton’s Tengo Casi 500 Años (I am nearly 500 years old), but when Renée Ater saw it, she could have sworn she was looking at herself.

Though the young girl in the photograph is sitting in Honduras, curator Virginia Mecklenburg says when Ater, a professor of art history at the University of Maryland, saw her, she said, “It’s like looking in a mirror from when I was that age.” Ater explained to Mecklenburg, “Getting your hair braided was something that involved community, it wasn’t one person who did all your braids. If people’s hands got tired or you got wiggly or something, people would shift off and so it became a way for a girl to be part of the women’s group.”

The idea of an individual encountering community and society animates much of the work in the American Art Museum’s exhibit, “African American Art: Harlem Renaissance, Civil Rights Era, and Beyond,” as is the case with Jacob Lawrence’s Bar and Grill, created after his first trip to the highly segregated South. But Mecklenburg, who will give her curator talk tomorrow says of the show, “In some ways it’s–I don’t know if I should say this out loud–but it’s sort of anti-thematic.” Organized loosely around ideas of spirituality, African diaspora, injustice and labor, the show jumps from artist to artist, medium to medium, year to year. The show features the work of 43 artists and several new acquisitions, including Lawrence’s painting. A huge figure in African-American art, Lawrence’s work can often overshadow artists dealing with divergent concerns.

One such artist was Felrath Hines who served as the head of the conservation lab first at the National Portrait Gallery and later at the Hirshhorn. Hines’ Red Stripe with Green Background sits surrounded by portraits and sculptures of found objects. In contrast to the cubist social realism of Lawrence’s pieces, Hines’ abstract geometric forms are calm and open, devoid of protest. “They are these incredibly pristine, absolutely perfectly calibrated geometric abstractions. There is a mood to each of them,” says Mecklenburg. He is an artist’s artist, having studied at the prestigious Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. And he is a black artist.

Mecklenburg wanted to organize a group of artists under the banner of African-American art to show how incredibly diverse that can be, that there was no one thing on the minds of black artists. “We tend to categorize things to make it easier to understand to help us understand relationships, but when you look at the reality it’s complicated, it’s a little messy.”

“We’re a museum of American art and one of our missions and convictions is that we need to be a museum representative of all American artists, of the broad range of who we are as a country,” says Mecklenburg. It’s an obvious statement now, but when the Metropolitan Museum of Art organized its 1969 exhibit, “Harlem On My Mind,” it decided not to feature any Harlem artists. Black artists, including Hines, protested the lack of representation not just in the exhibit ostensibly about Harlem, but in major permanent collections as well.

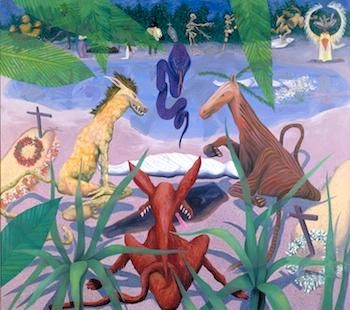

The show also benefits because Mecklenburg knows many of the artists personally. She knows, for instance, that Keith Morrison’s bizarre painting Zombie Jamboree is not just a study of the interwoven religious traditions Morrison grew up with in Jamaica, but a fantastical memory from his childhood. “One of his friends had drowned in a lake when they were boys,” says Mecklenburg, “especially when you’re a young kid, you don’t know where your friend has gone and you don’t know what’s happened to him, but you hear stories. So you have this incredible, vivid imagination–he certainly did.”

Rather than create a chronology of artistic development, Mecklenburg has created a constellation, a cosmic conversation each artist was both a part of and distinct from.

“What I’m hoping is that people will see a universe of ideas that will expand their understanding of African-American culture, there isn’t anything monolithic about African-American culture and art. I’m hoping that they will come away seeing that the work is as diverse, as beautiful, as far-ranging aesthetically and in terms of meaning and concept as art in any other community.”

See a slideshow of images in the exhibit here.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)