Dave Brubeck’s Son, Darius, Reflects on His Father’s Legacy

As a global citizen and cultural bridge-builder, Dave Brubeck captivated the world with his music, big heart and a vision of unity

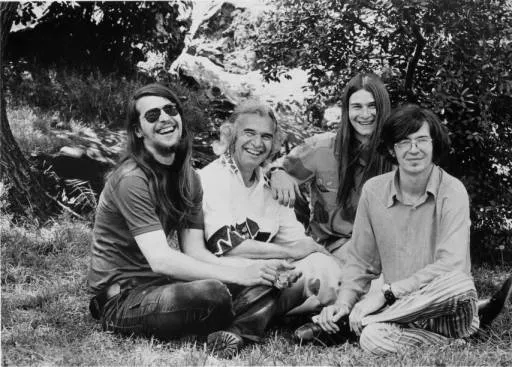

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/20130402094041DBGroup_Thumb.jpg)

Dave Brubeck. The legendary jazz pianist, composer, and cultural diplomat’s name inspires awe and reverence. Call him the “quintessential American.” Reared in the West, born into a tight knit, musical family, by age 14 he was a cowboy working a 45,000 acre cattle ranch at the foothills of the Sierras with his father and brothers. A musical innovator, Brubeck captivated the world over six decades with his love for youth, all humanity, and the cross-cultural musical rhythms that jazz and culture inspire. In 2009, as a Kennedy Center Honoree he was feted by President Barack Obama who said “you can’t understand America without understanding jazz. And you can’t understand jazz without understanding Dave Brubeck.”

In 2012, Dave Brubeck passed away a day before his 92nd birthday, surrounded by his wife of 70 years, Iola , his son Darius and Darius’ wife Cathy. To understand Brubeck’s legacy one must know him as a musician, a son, husband, father and friend. In tribute to Dave Brubeck during the Smithsonian’s 12th Annual Jazz Appreciation Month (JAM) and UNESCO’s International Jazz Day, his eldest son, Darius, offers a birds-eye view into life with his famous father and family and how their influences shaped his personal worldview and career as a jazz pianist, composer, educator, and cultural activist, using music to foster intercultural understanding and social equity. A Fulbright Senior Specialist in Jazz Studies, Darius Brubeck has taught jazz history and composition in Turkey, Romania, and South Africa, among other nations. He has created various ground breaking commissions such as one for Jazz at Lincoln Center that set music he composed with Zim Ngqawana to extracts of speeches from Nelson Mandela and Desmond Tutu, read by actor Morgan Freeman.

What did you learn from your father as a musician and cultural ambassador that guides and inspires you today?

Nearly everything. But here is what I think relates to JAM and this UNESCO celebration. Dave combined being as American as you can get—raised as a cowboy, former GI, always in touch with his rural California roots—with being internationalist in his outlook. People in many countries regard him as one of their own, because he touched their lives as much as their own artists did. If it were possible to explain this with precision, music would be redundant. Of course it isn’t.

He was always curious, interested in people, intrigued rather than repelled by difference, and quick to see what people had in common. I realize, now especially, that I absorbed these attitudes and have lived accordingly, without really thinking about where they came from.

How was it growing up with a famous jazz musician father who had friends like Louis Armstrong, Gerry Mulligan and Miles Davis?

In retrospect, the most important thing was seeing what remarkable human beings these musicians were. They had their individual hang-ups and struggles, but in company they were witty, perceptive, self-aware, informed, and, above all, ‘cool.’ I learned that humor and adaptability help you stay sane and survive the endless oscillation between exaltation and frustration— getting a standing ovation one moment and not being able to find a place to eat the next. Dave and Paul (Desmond) were extremely different people but their very difference worked musically. You learn perspective because your own vantage point is always changing.

For your family music, and jazz in particular, is the family business. How did that shape you as a person and your family as a unit?

It made us a very close family. People in the ‘jazz-life’ really understand that playing the music is the easiest part. The rest of it can be pretty unrewarding. My mother worked constantly throughout my father’s career, and still does. Many people contact her about Dave’s life and music. In addition to writing lyrics, she contributed so much to the overall organization of our lives. We were very fortunate because this created extra special bonds between family members as colleagues, and as relatives.

Performing together as a family is special. It’s also fun. We all know the score, so to speak. We all know that the worst things that happen make the best stories later. And so we never blame or undermine each other. There have been big celebratory events that have involved us all. Dave being honored at the Kennedy Center in 2009 must count as the best. All four musician brothers were surprise guest performers, and both my parents were thrilled.

During the seventies, my brothers Chris and Dan and I toured the world with Dave in “Two Generations of Brubeck” and the “New Brubeck Quartet.” Starting in 2010, the three of us have given performances every year as “Brubecks Play Brubeck.” We lead very different lives in different countries the rest of the time. The professional connection keeps us close.

The Jazz Appreciation Month theme for 2013 is “The Spirit and Rhythms of Jazz.” How does your father’s legacy express this theme?

I know you’re looking for something essential about jazz itself but, first, I’ll answer your question very literally. Dave wrote a large number of ‘spiritual’ works, including a mass commissioned for Pope John Paul’s visit to the U.S. in 1987. His legacy as a composer, of course, includes jazz standards like In Your Own Sweet Way. But there is a large body of liturgical and concert pieces in which he shows people how he felt about social justice, ecology, and his faith.

The ‘spirit of jazz’ in Dave’s music, as he performed it, is an unqualified belief in improvisation as the highest, most inspired , ‘spiritual’ musical process of all.

Cultural and rhythmic diversity is what he is most famous for because of hits like “Take Five,” “Unsquare Dance” and “Blue Rondo a la Turk.” The cultural diversity of jazz is well illustrated by his adaptation of rhythms common in Asia, but new to jazz. He heard these during his Quartet’s State Department tour in 1958.

You were a Fulbright scholar in jazz studies in Turkey. Your father composed “Blue Rondo” after touring the country. How did Turkey inspire him? What did you learn from your time in Turkey and touring there with your father?

Dave first heard the rhythm that became the basis of “Blue Rondo a la Turk” in Izmir, played by street musicians. I was actually with him in 1958, as an 11-year-old boy. He transcribed the 9/8 rhythm and when he went to do a radio interview, he described what he heard to one of the radio orchestra musicians who spoke English. The musician explained that this rhythm was very natural for them, “like blues is for you.” The juxtaposition of a Turkish folk rhythm with American blues is what became “Blue Rondo.”

The Dave Brubeck Quartet’s music encounter with Indian classical musicians at All-India Radio was also very significant. Dave didn’t perform the music of other cultures, but he saw the creative potential of moving in that direction as a jazz musician, especially when it came to rhythm.

Jazz is open-ended. It always was fusion music, but that doesn’t mean that it is just a nebulous collection of influences.

When I was in Istanbul as a Fulbright Senior Specialist in 2007, my first thought was to encourage what musicologists call hybridity, the mixing of musical traditions. This was met with some resistance from students and I had to re-think my approach. In effect, they were saying, ‘No! We’re not interested in going on a cross-cultural journey with you during your short time here. We want to learn what you know.’

They were right. When, and if, they want to combine jazz and Turkish music, they’ll do it themselves, and vice versa. Jazz is world music. It’s not ‘World Music’ in the sense of ‘Celtic fiddler jams with Flamenco guitarist and tabla player.’ Rather it is a language used everywhere. Anywhere you go you’ll find musicians who play the blues and probably some ‘standards’ like “Take the A-Train” or “All the Things You Are.” The other side of this is that local music becomes international through jazz. Think about the spread of Brazilian, South African and Nordic jazz.

In the eighties in South Africa, you initiated the first degree course in jazz studies offered by an African university. Jazz is known globally as ‘freedom’s music.’ South African was under apartheid when you did this. Why was it important for you to do this on that continent, in that country, at that time?

Before I answer, I have to say that my wife, Catherine, is South African. Her political and music connections led to my going to Durban in 1983 to teach at the University of Natal (now the University of KwaZulu-Natal).

There wasn’t a university degree in jazz studies in the whole of Africa. It is somewhat ironic that the first one should be taught by a white foreigner in apartheid South Africa. The ANC in exile was in favor of my going or we wouldn’t have gone. They knew they would be in government sooner or later and saw that transforming important institutions from the inside was a positive step.

There was already an established jazz scene in South Africa that had produced great artists like Hugh Masakela and Abdullah Ibrahim, but they couldn’t work in their own country. So this was a crucial choice for me at the time and an opportunity to do something that mattered. Local musicians didn’t have the training for the academic world; working in a university certainly isn’t the same as gigging and giving music lessons. A lot of ‘improvisation’ made it work. For example, changing entrance requirements so that African students and players could join the program.

How we progressed is too long a story to go into here, but the new opportunities and, eventually, the especially created Centre for Jazz & Popular Music visibly and joyfully changed the cultural landscape on campus, in Durban, and also had an impact on higher education generally. Today, 30 years later, there are numerous universities and schools that offer jazz.

What are your aspirations as a jazz musician and educator? What impact do you want to have on the world?

I’ve just described the biggest thing I’ve done in my life. It took up almost 25 years and I’m in my sixties now. So that might be it, but who knows? I’m back to playing music full-time because I love doing it, not just the music but the life-long friendships and connections that develop in the jazz world.

Also the travel, the especially strange and wonderful opportunities like playing in Israel and Saudi Arabia within a few months of each other. I secretly hope that in some instances my concerts and compositions help people see beyond the barriers of race, nationalism and ideology. That’s what I try to do, anyway.

I don’t have particular career aspirations, except the desire to continue improving as a musician. When I feel I’ve gone as far as I can, I’ll quit. Meanwhile I enjoy having my own quartet, touring sometimes with my brothers, and also lecturing and teaching when the occasions arise.

What’s on the horizon for the Brubeck Institute and your career that most people don’t know?

I hope the Brubeck Institute will take on an even more international role. While it is historically fitting that the Institute and the Brubeck Collection be located at the University of the Pacific in California where my parents studied and met, the true mission is global.

At the start of this conversation I said my father was instinctively internationalist. I think the Brubeck Institute should carry this spirit of cooperation and ecumenism into the future. I will certainly help where I can.

This year I’m hoping to play in far flung Kathmandu, where they have a jazz festival, also to return to South Africa for some reunion performances. I really appreciate that although I live in London, the university where I taught for 25 years has made me an Honorary Professor.

JAM 2013 explores jazz and world culture with Smithsonian museums and community partners in a series of events. April 9, free onstage discussion/workshop with Horacio “El Negro” Hernandez at American history; free Latin Jazz JAM! concert with Hernandez, Giovanni Hidalgo and Latin jazz stars at GWU Lisner Auditorium; April 10, Randy Weston and African Rhythms in concert w. guest Candido Camero/onstage discussion with Robin Kelley and Wayne Chandler ; April 12 Hugh Masakela at GWU.

Use of historic materials in the Brubeck Collection are granted by permission of the Brubeck Institute at the University of the Pacific.