Deeply Grieving MLK’s Death, Activists Shaped a Campaign of Hurt and Hope

At Resurrection City, an epic 1968 demonstration on the National Mall in Washington D.C., protesters defined the next 50 years of activism

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/85/11/8511f9fd-0dca-4524-bb9e-a650dc7b7fa7/2017_81_10_001.jpg)

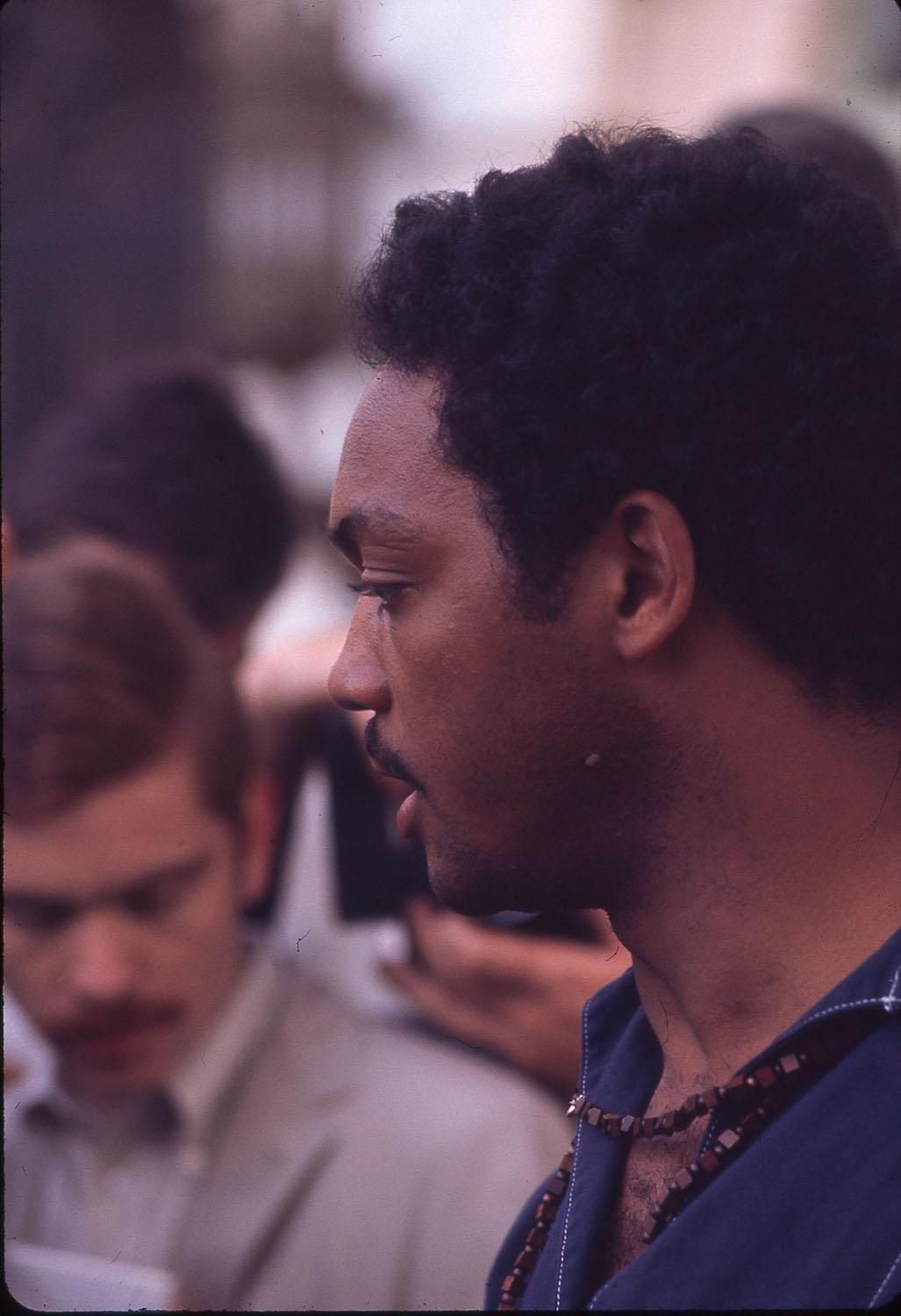

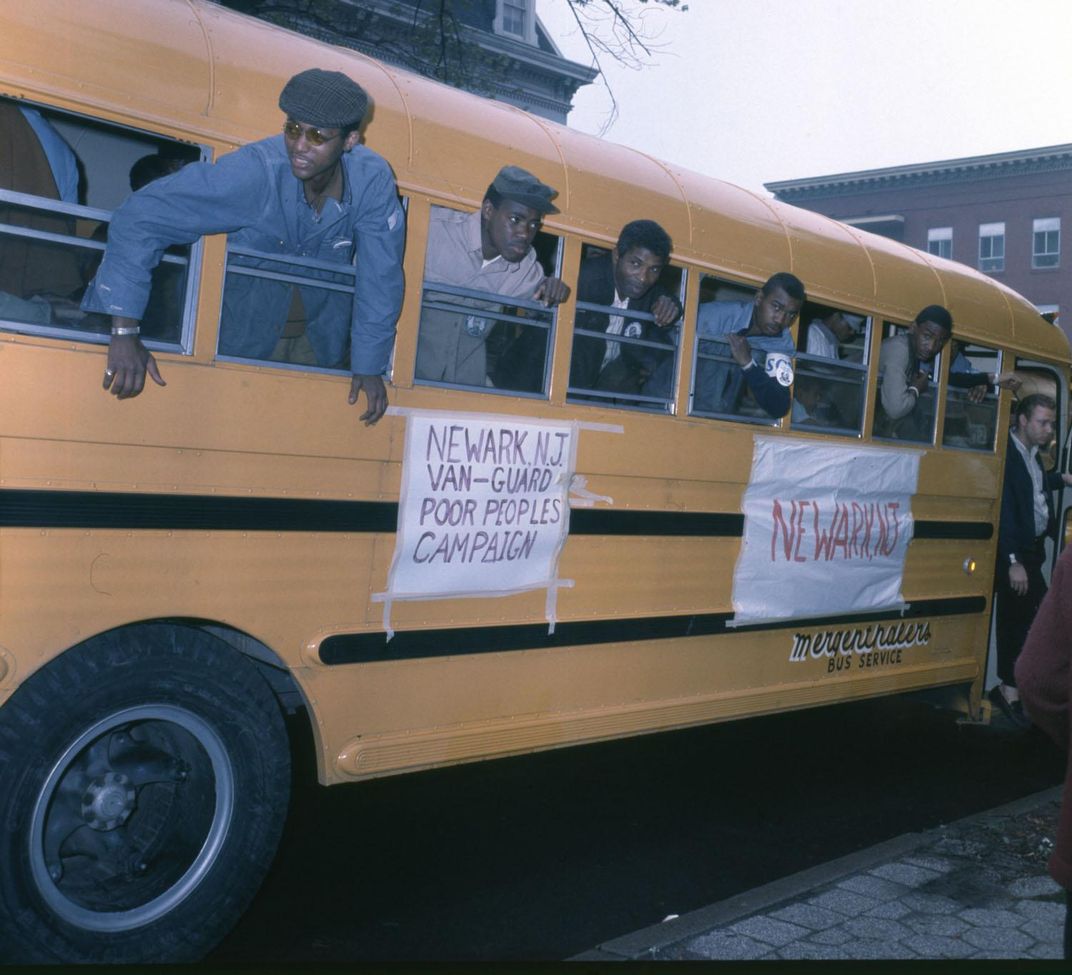

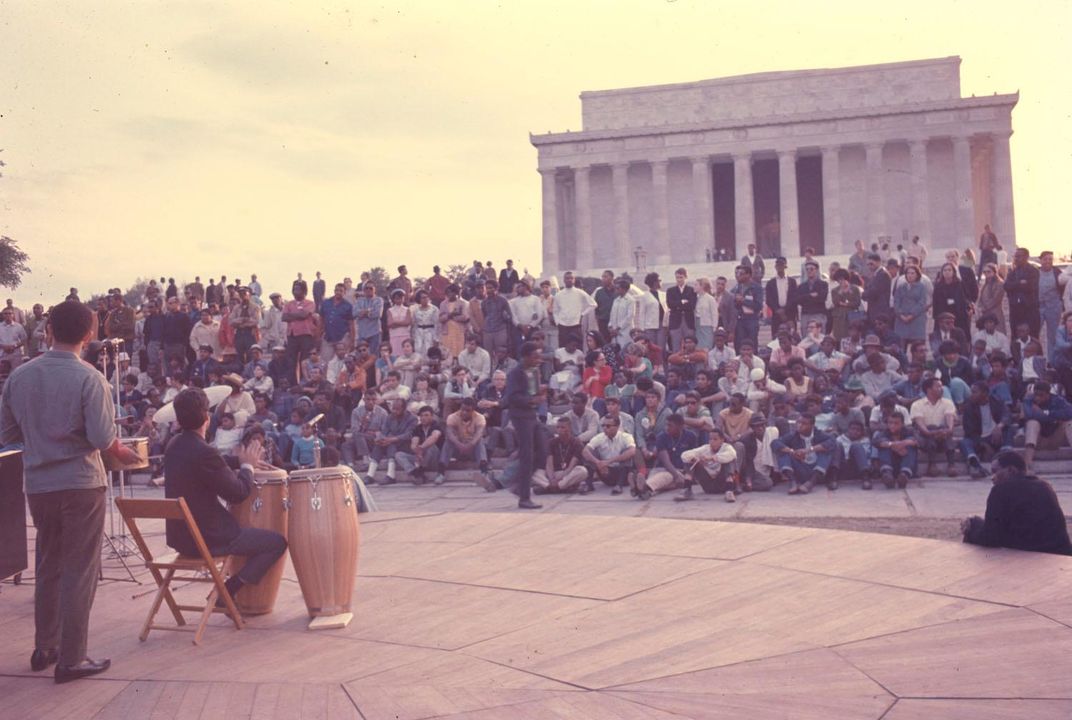

Robert Houston’s eyes mist over as he recalls what it was like when he arrived to photograph the Poor People’s Campaign on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. in May of 1968. The campaign was conceived by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as a multicultural battle for economic justice for the nation’s poor. King had been assassinated the month before on April 4, but organizers carried on and galvanized African, Mexican and Native Americans, Puerto Ricans, Asians and poor whites from Appalachia and rural areas to descend on Washington for an epic demonstration.

“It was a little scary that people were coming from the four corners of the United States. Strangers. People who didn’t know or barely knew each other and really didn’t care for each other. But the one thing they had in common was they had nowhere else to go,” says Houston, who covered the event for Life Magazine. “You were there for a purpose. . . . You had aches and pains just like everyone else. So it sort of made it bearable. But there was little trust between people only because they were strange to each other.”

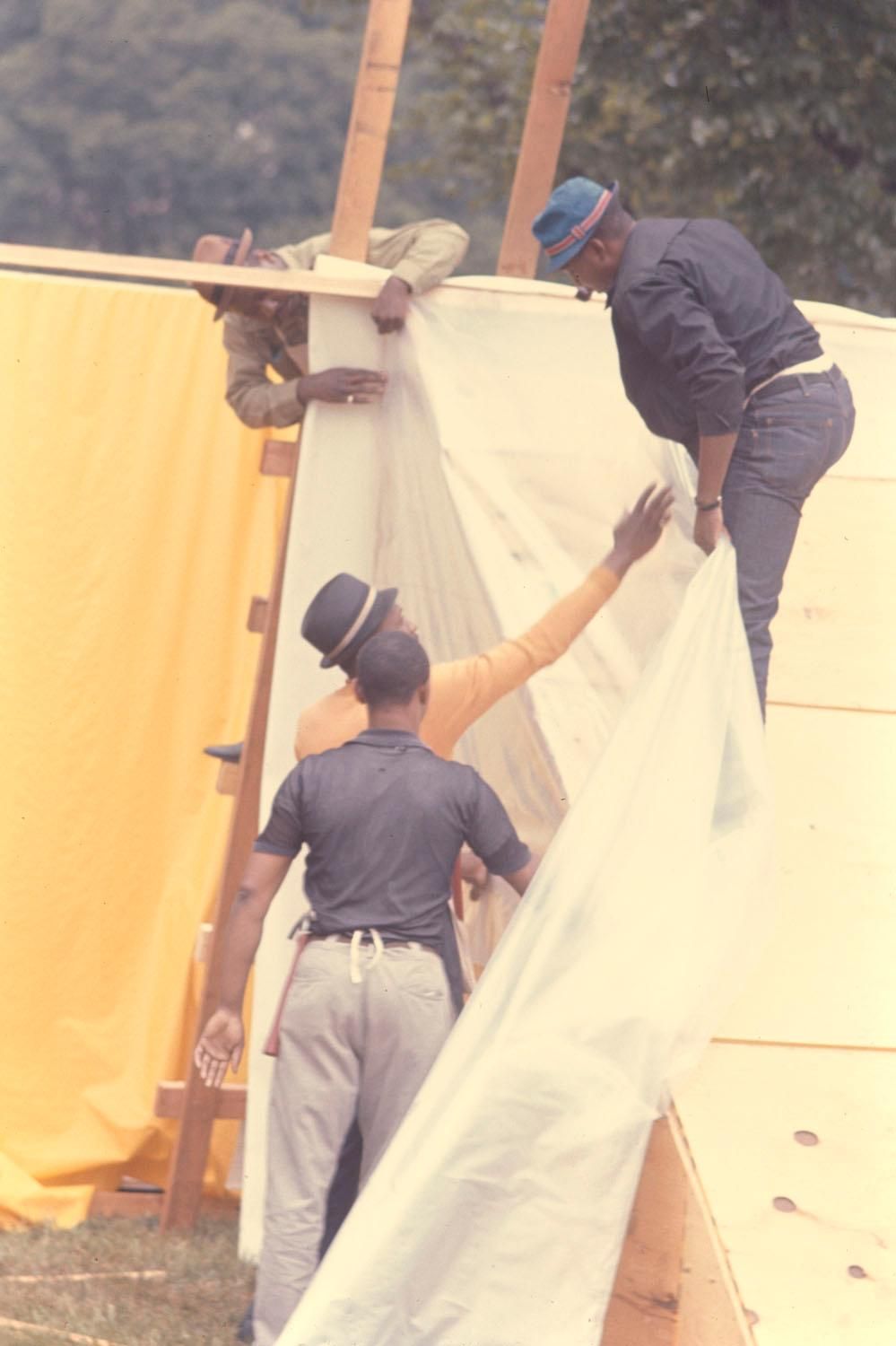

Houston got there two or three days before Resurrection City—a live-in demonstration with a shantytown settlement that existed for six weeks on the National Mall—was even built. But he saw things that made it easier for him to understand the depth of this campaign, and how deeply people were committed to supporting each other. First, Houston met a group of African American teens, holding a newspaper upside down, who wanted to know if he could read it to them. Later, while he continued to take pictures, he saw extraordinary things.

“One white guy threw up the peace sign and said, ‘Good Morning brother.’ . . . It was exciting and scary,” Houston says of the unexpected display of camarderie. Then there was the incident in front of the Department of Justice, where a black man who wasn’t participating in the Resurrection City protest joined a demonstration being watched by police officers lining both sides of the street. “He threw up his right hand, clenched fist, and all he said was ‘Black is beautiful.’ The cops rushed in, took him to the ground. . . . I photographed this and four cops are coming toward me. I started to back up, and I hear people saying ‘tell our story.’ I turn around and look back on hundreds of people. I had no idea.”

Houston’s pictures— some rarely or never seen before— are among those on display in a new exhibition called “City of Hope: Resurrection City & the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign.” The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture is organizing this exhibition, on view at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. The new show complements the exhibition “American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith,” which explores the history of citizen participation.

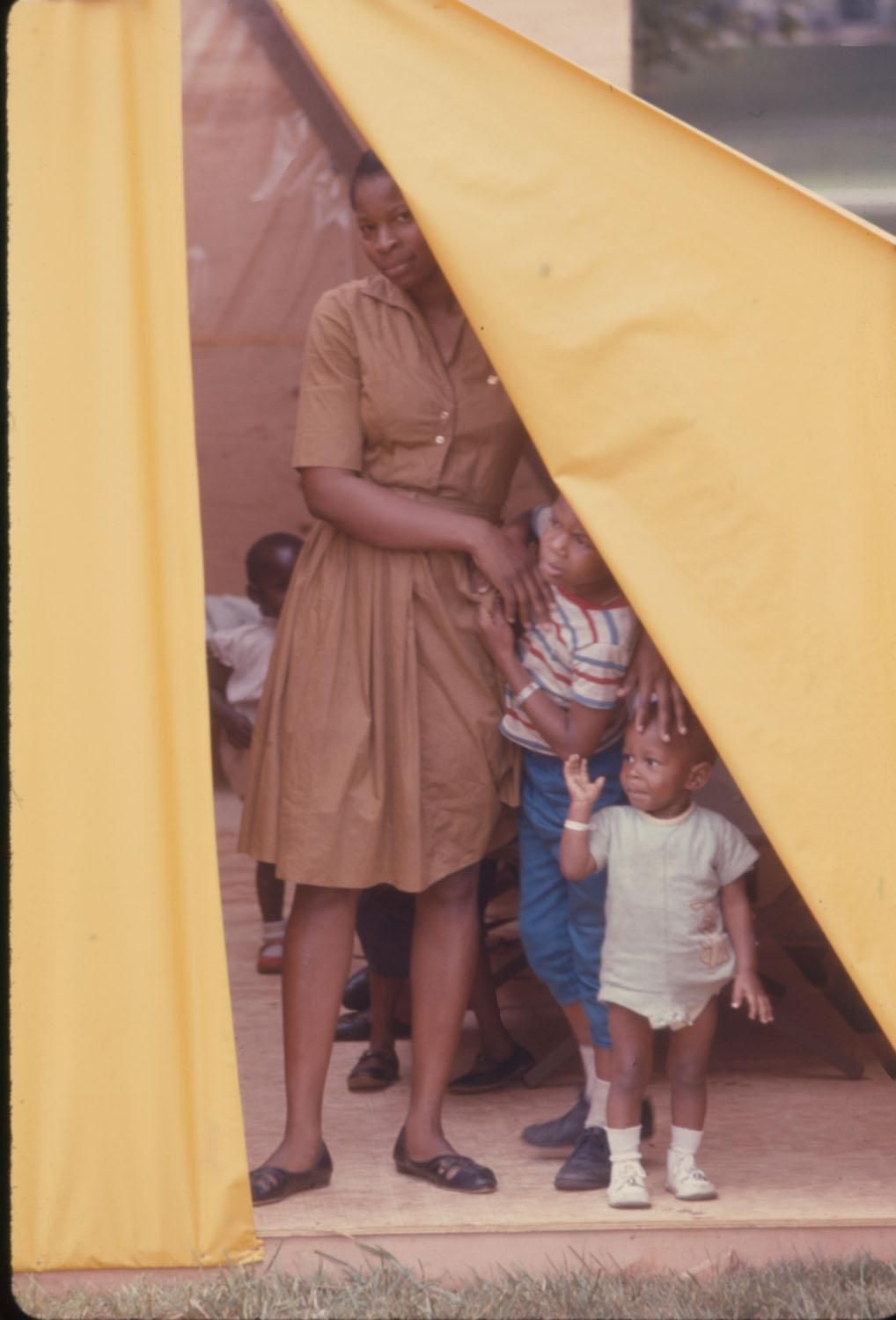

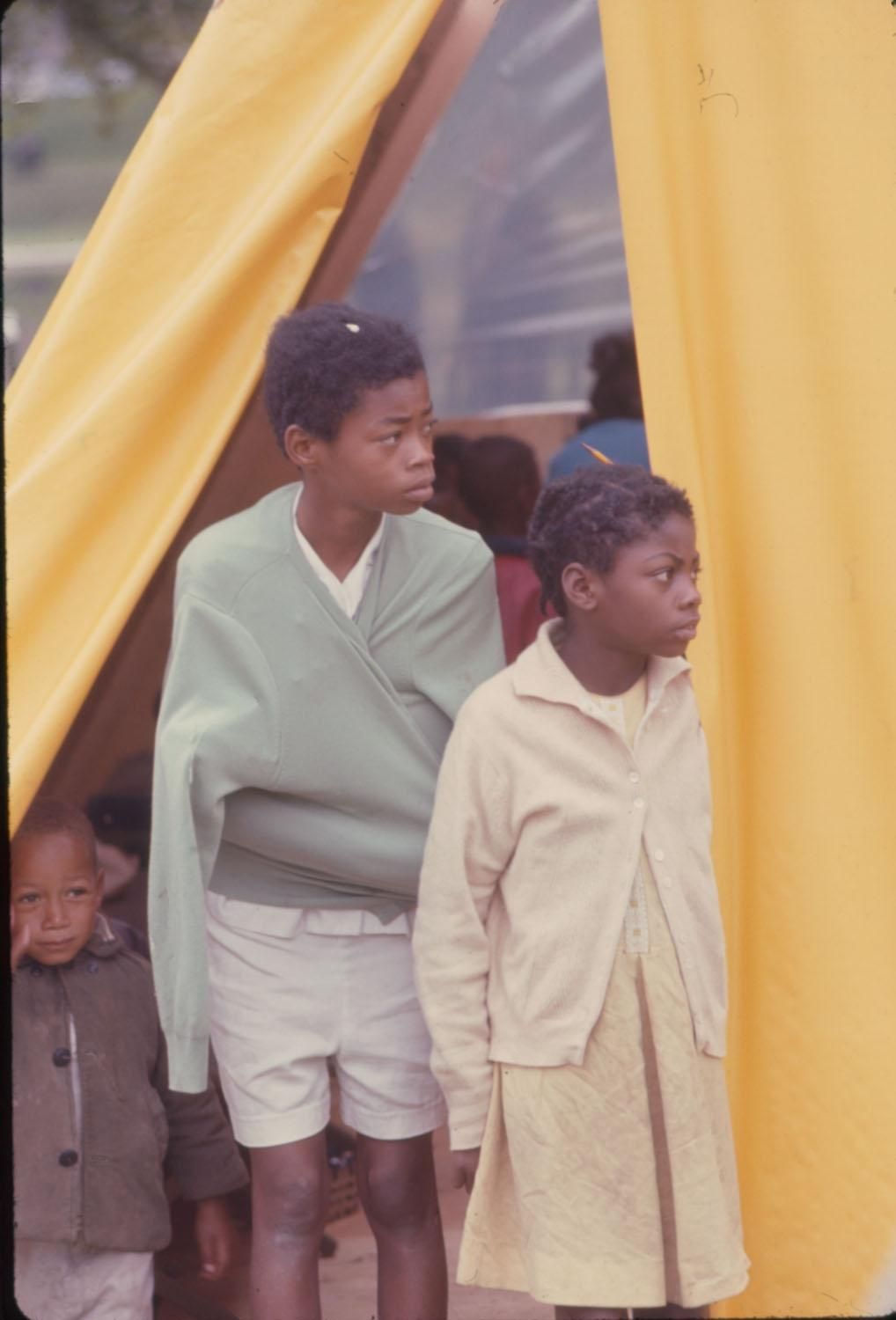

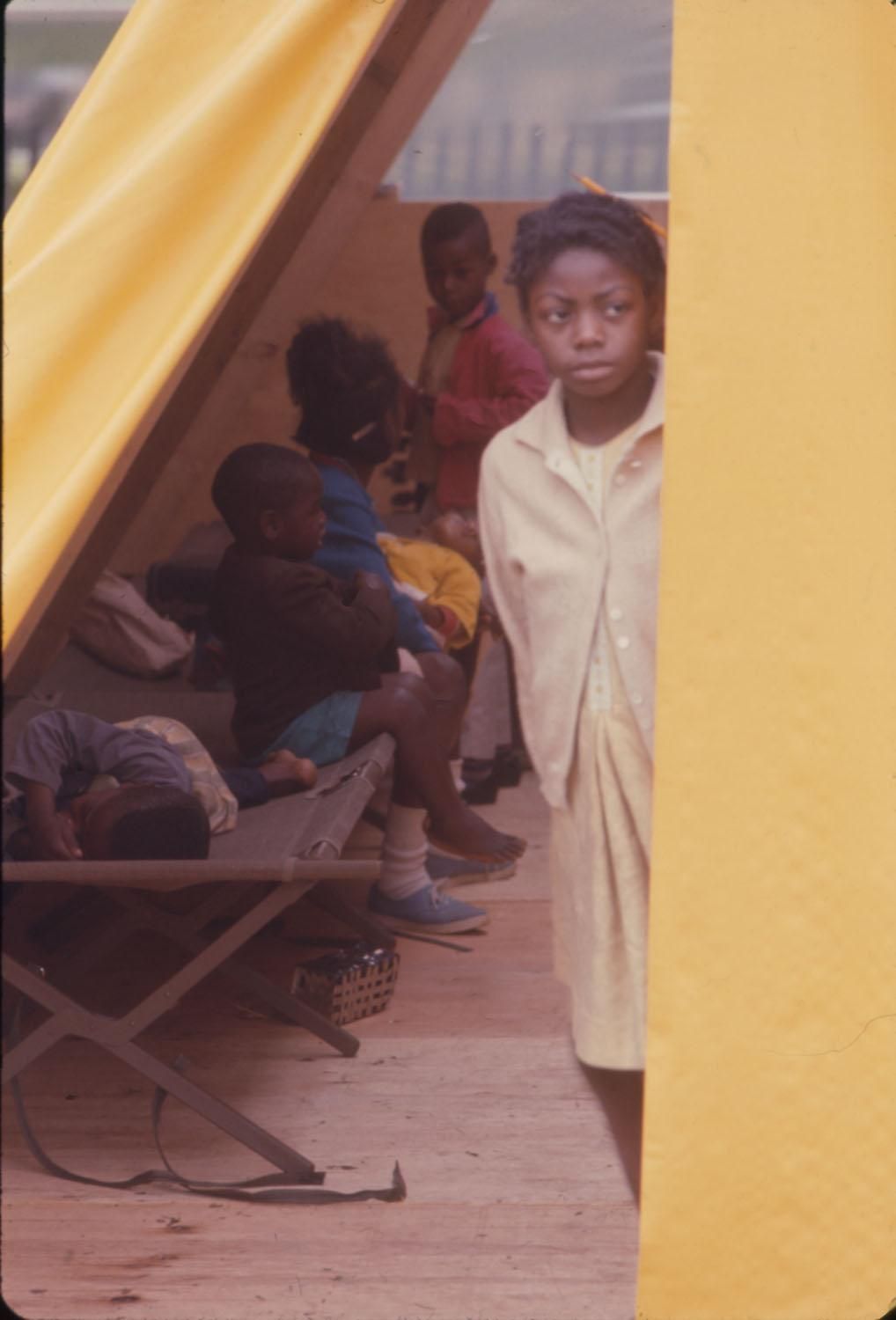

“City of Hope” features film produced by the Hearst Corporation that has never been on public display before, showing how some 3,500 people built and lived in the tent city. It was so large that the U.S. Post Office issued the settlement a zip code. There is footage of a caravan of wagons drawn by mules carrying people from Marks, Mississippi, to Memphis, Tennessee, for King’s memorial service, and then on to Washington, D.C. and Resurrection City.

“We found about two and a half hours of footage. and made some selections to work with the exhibition’s narrative to get it down to about 15 minutes,” explains Aaron Bryant, curator of “City of Hope.” He adds that it was important to the museum’s project team to focus on the fact that protest was a multicultural movement, during a time when the civil rights movement was transitioning towards a human rights agenda.

“You know anything related to labor, or anything related to unemployment benefits, or health care, affects all of us and affects the quality of our lives and it affects our ability to actually live the American dream,” Bryant says. “We’re not just talking about things that are totally race specific, or even if they are, King is saying . . . and all the other organizers of the campaign are saying . . . we’re going to show you how the issues affecting Chicanos and Mexican immigrant farmers affects you as a white person in Mississippi. I think that’s one of the things that made this movement so incredible.”

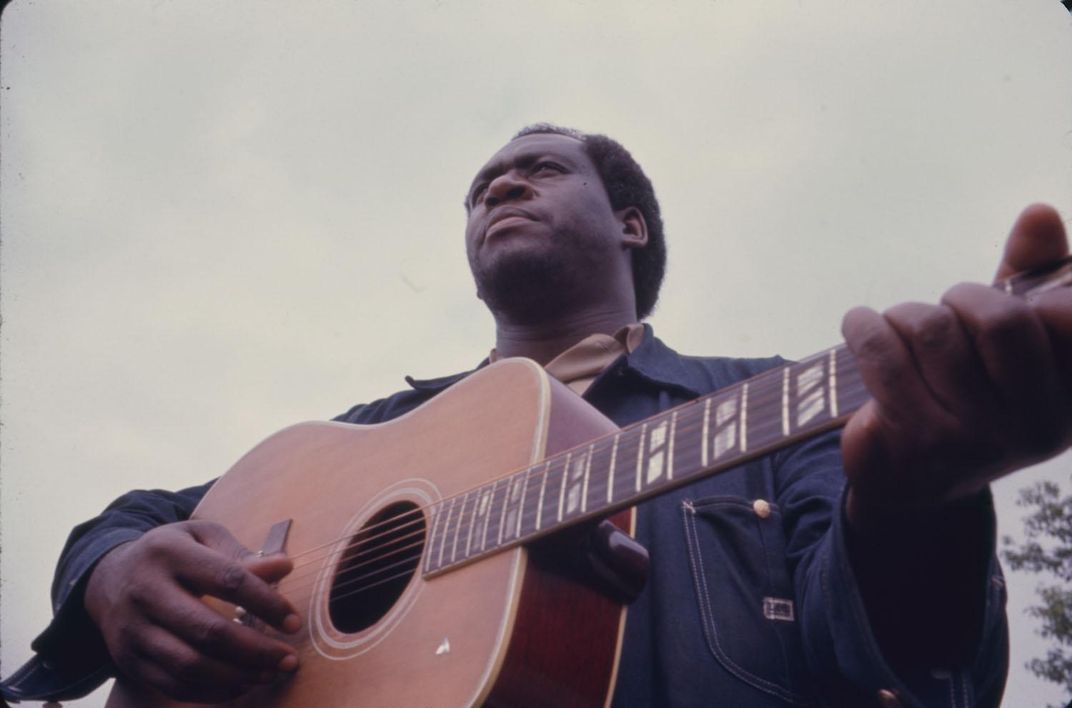

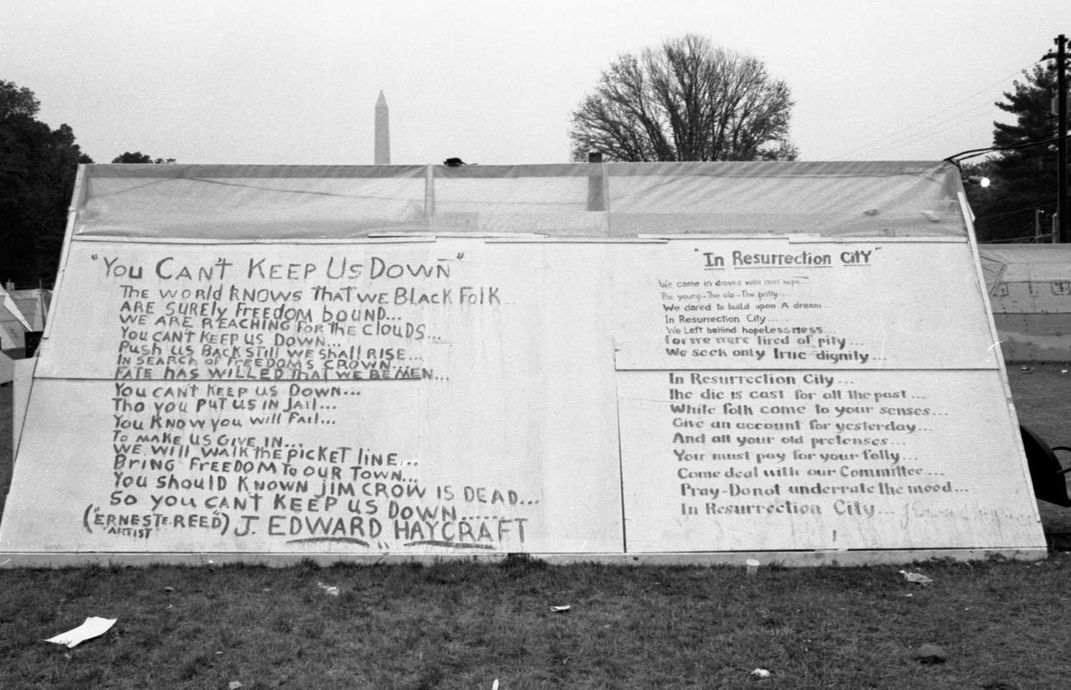

Bryant says “City of Hope” intentionally brings different objects from different Smithsonian museum collections from the Poor People’s Campaign into one exhibition—multicultural, across regions and cultures as a metaphor for the movement. There’s a huge panel from the inside of an actual tent from Resurrection City, with a large painted red Peace Sign filled in with yellow, next to a blue-green symbol reminiscent of an Asian dragon. There’s a plethora of lapel buttons and placards and pieces of murals. There is sheet music and lyrics from Jimmy Collier and Rev. Frederick Douglass Kirkpatrick, who were, Bryant says, responsible for the cultural programming in Resurrection City. There are also actual recordings of that music collected by Ralph Rinzler and the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage.

There’s even surveillance video of Resurrection City taken by the U.S. Army Signal Corps. When you first look at the aerial video taken of the encampment, it looks like the same picture. But then, you begin to see some differences.

“The Signal Corps went to the top of the Washington Monument and periodically during the day, would turn on a video recorder and just videotape Resurrection City,” Bryant says, gesturing at three blocs of video projected on a wall at the exhibition. “The first bloc is Resurrection City early in the course of six weeks. You can still see grass and it is moderately dry. The one in the middle is Resurrection City after the infamous rains and floods—you don’t see grass anymore it’s all just brown and mud. Then the last square is Resurrection City after it’s been demolished and people had been evacuated.”

But before the evacuation, there was a huge demonstration on June 19, 1968, as a sea of 50,000 rolled out from the Lincoln Memorial on what was known as Solidarity Day.

As impressive as the 1968 protest was, scholars such as Bryant, and more than a few activists, believe the battle against poverty and its effects must continue.

“One of the things this exhibition is about is that you know just because these protest movements happened in the 1960s doesn’t mean that the fight is over,” Bryant says. “The rights and gains we were able to make during the 1960s came because people really had to commit to something and they had to fight. Today, . . you have a lot of people who consider themselves activists because they’re activists on social media. . . . That’s very different from Marion Wright, being a 27-year-old, a year out of Yale Law School, and deciding to move to Mississippi . . . and fight for the rights of poor black people.”

Marion Wright Edelman was among the organizers of the Poor People’s Campaign, along with fellow civil rights activists Ambassador Andrew Young and Ralph Abernathy. Her husband, activist, lawyer and policy maker Peter Edelman, says as the nation celebrates King’s birthday and the 50th anniversary of the Poor People’s campaign, there is much work yet to be done.

“We don’t have the good jobs that were there after World War II into the 1970s. The de-industrialization of our country has left us . . . we are a low-wage nation and nobody in our leadership . . . is really addressing that,” Edelman said last week at a press conference announcing the opening of the “City of Hope” exhibition. “There’s a long list of things we need to do. We need to end mass incarceration. We need to improve our education. We need to have affordable housing. There’s a long list of things, but the absolute heart of it is jobs, just as it was in 1963, just as it was in 1968.”

The African American History Museum’s Founding director Lonnie Bunch visited Resurrection City at the tender age of 14, and was struck with the level of sacrifice people were willing to endure to change the country. As a historian looking at what many scholars consider to be King’s final human rights crusade, Bunch says part of the thinking behind “City of Hope” was to return the notion of poverty to the national discourse. It also reminds the nation that a group a multicultural, multi-racial people shaped a campaign of hurt and hope out of a tumultuous year including the war in Vietnam, and the assassinations of King and then Robert F. Kennedy.

“We tend to view those who protest in a certain box. What that movement did was say, you have a responsibility regardless of race because you’ve all been touched by the pain and the power of poverty,” says Bunch. “I think the challenge is that 50 years ago the notion was that on one hand you had to stimulate the economy. . . . On the other hand you had to create programs whether to feed the hungry or even Headstart. So the notion was you had to use both hands—you couldn’t just use the hand of economic opportunity.”

Bunch says the difference today is that instead of there being a safety net; there is the notion that simply creating economic opportunity is enough.

“Ultimately, this exhibition posits that average citizens can help make America better,” Bunch says. “The best way to honor the ultimate sacrifice of Dr. King is to cross those boundaries that divide, boundaries of race, gender, ethnicity, to demand a fair and free America.”

A group of faith leaders, including the Rev. Dr. William Barber II and Rev. Liz Theoharis, have launched an updated version of the battle, called “Poor People’s Campaign: A National Call for Moral Revival.” It has been organizing for months, and a series of mobilizations and some acts of civil disobedience are planned for this spring.

The “City of Hope: Resurrection City & the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign,” organized by the National Museum of African American History and Culture, is on view at the National Museum of American History.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)