From This Desk, 100 Years Ago, U.S. Operations in World War I Were Conceived

Germany’s defeat could be traced to pins in a map now on display at the Smithsonian’s American History Museum

In the 21st century, the military’s central command usually means a buzzing operation of video screens, soldiers, updated data, visual reconnaissance and computer communications.

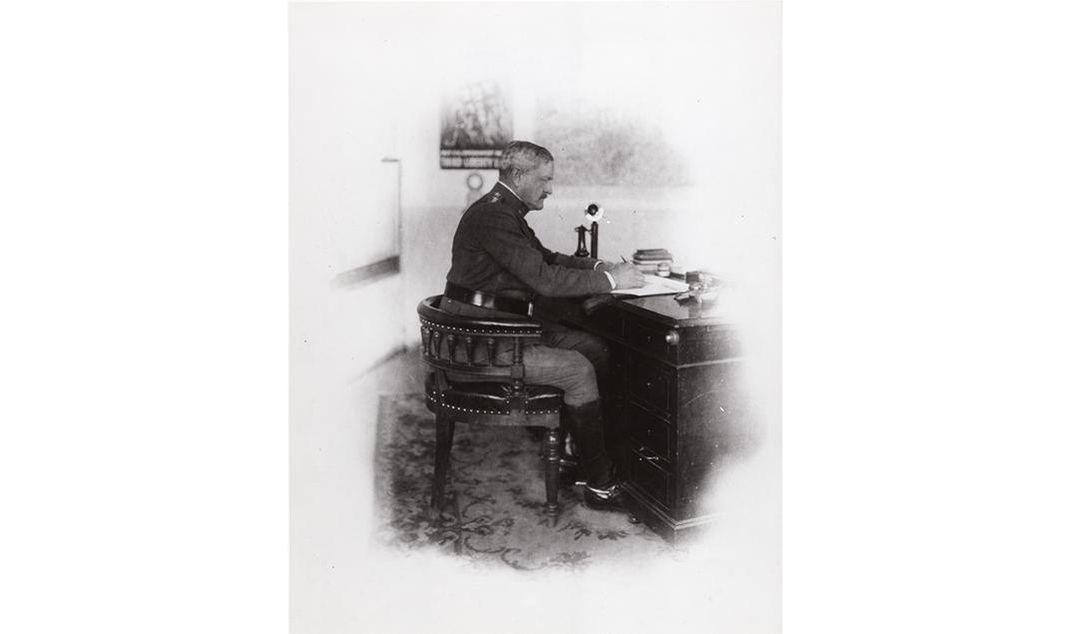

But just a century ago, central command for Gen. John J. Pershing at the height of World War I was a solid chair, a desk and a huge map marked with pins denoting troop movement.

All are currently on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. as part of a compact exhibition, entitled "Gen John J. Pershing and World War I, 1917-1918" that sets the scene of Pershing’s war room in Damrémont Barracks in Chaumont, France.

“That was central command for Pershing,” says Jennifer Locke Jones, the museum’s curator of Armed Forces history. “Pershing directed the American forces in that office. That was his chair, his desk.”

A central command for battle plans “is all the same idea, and the same premise” a century later, whatever the technology, she says. “How it gets done is very different.”

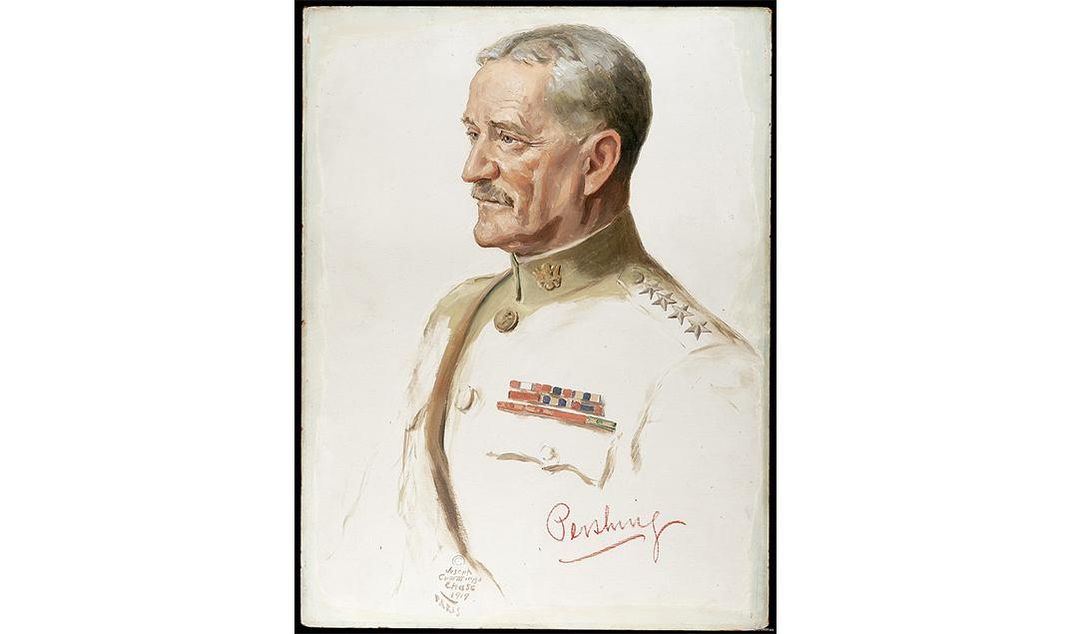

When it came to Pershing, a war hero of the Spanish-American War who later went after Pancho Villa in Mexico before he was named head of the American Expeditionary Forces in World War I, the general was used to following his own path—favoring, for example, frontal assaults over trench warfare.

“The thing about Pershing is that he conducted the war in a very different way than the other forces wanted him to,” Jones says. “They wanted us to throw men in the French army and put them in with all the Allies and he refused. He wanted to keep them separate. And because he kept them separate, he ran the war the way he wanted to.”

It was effective—the addition of American troops in the war’s final months helped lead to victory over Germany in November, 1918.

And while a lot of technology for World War I was new, including the use of planes, heavy artillery, and telephone communication, the bulk of Pershing’s strategy was done with a big map and pins.

The original map is in the Smithsonian collection but could not be put on display, because of light sensitivity issues and the length it will be on display—until 2019.

But the original was photographed with the highest resolution photography to make a full scale replica affixed with pins, Jones says.

“It’s supposed to represent the battlefront at the time of the Armistice,” she says of its pin placements. “But the date on it was a week before the Armistice, and of course they didn’t update it. It was a stalemate, so the battle line did not change in that last week.”

As it happens, the portrait of Pershing by Joseph Cummings Chase on display is also a replica. The original was awaiting framing at the time the exhibit opened to commemorate the 100th anniversary of the U.S. declaring war on Germany to enter the war that had been raging for two and a half years.

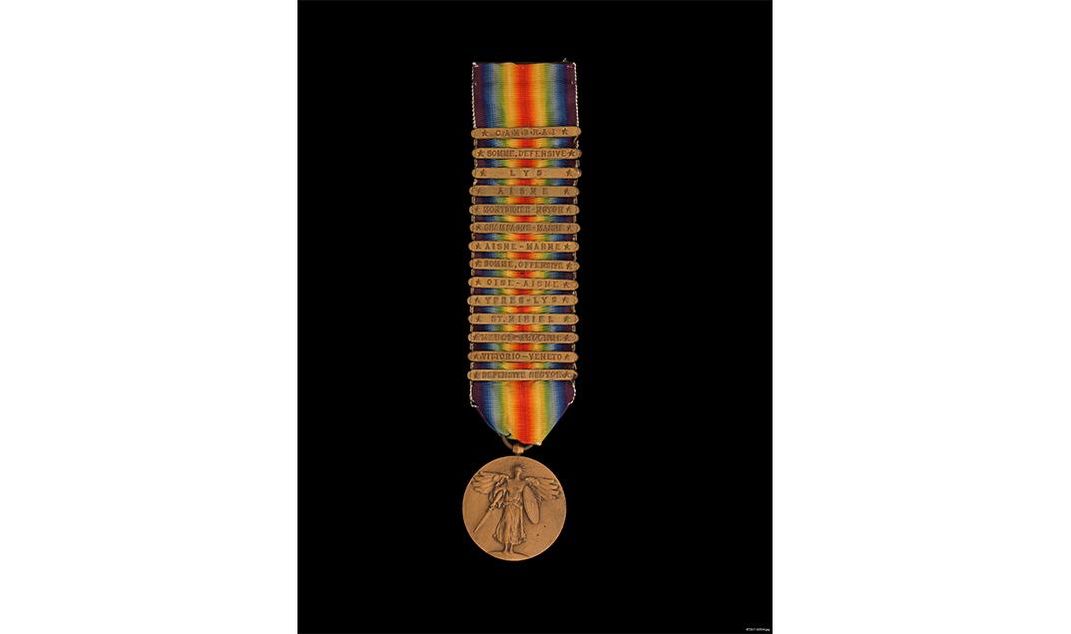

It is Pershing’s actual World War I victory medal that is shown, however, hanging from a long ribbon festooned with a clasps from each major battle for the American troops in the war.

“He’s the only one that received as many battle clasps,” says Jones.

The desk itself is cleaner than depicted in period pictures—or when it was more recently on display as part of the museum's “West Point in the Making of America” exhibition from 2002 to 2004.

Because the desk is seen in open air instead of behind glass, there are none of the plentiful books or papers on the desk.

“Somebody might want to reach over and grab an artifact off the desk, so we didn’t put anything on it,” Jones says. “But we have all of the material that should be on there in the collections.”

There’s nothing particularly special about the desk and chair. “It’s not French Provincial furniture,” the curator says. “We’re assuming it’s American.”

But once the war was won, “they had the wherewithal of taking everything out of that room and putting it in crates and sending it to the United States.”

And when it arrived, “his officers and his team came over, brought the map over and assembled it for the Smithsonian Institution,” Jones says. “This was right after the war, and they put all the pins back and recreated the map.”

It’s one of several displays at the history museum that note the centenary of America’s involvement in the huge conflict that many have forgotten or never knew.

“Most people don’t even know who fought in World War I,” Jones says, though many things that resulted from orders given in that modest office continue to have lingering consequences in the world.

“Gen. John J. Pershing and World War I, 1917-1918” continues through January 2019 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)