Dian Fossey’s Gorilla Skulls Are Scientific Treasures and a Symbol of Her Fight

At a new Smithsonian exhibition, the skulls of “Limbo” and “Green Lady” have a story to tell

:focal(1341x519:1342x520)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e9/5b/e95beb29-90c3-44bd-9cd8-9ca6eee91ce4/_mg_9262.jpg)

At first glance, the two gorilla skulls on display in a new exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History are unremarkable, except for maybe their size. But these skeletal remains are intertwined with the fascinating personal story of one of the nation’s pioneering female anthropologists, Dian Fossey. And they speak to the remarkable scientific achievements she helped bring about—including helping create a skeletal repository of a key Great Ape species—the mountain gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei)—and putting the brakes on the potential extinction of that critically endangered species.

One skull belonged to Limbo, a male mountain gorilla, and the other came from Green Lady, a female from the same species. Fossey shipped both to the Smithsonian Institution in 1979, for further research. The skulls are now on view in the new exhibition, “Objects of Wonder,” that examines the role that museum collections play in the scientific quest for knowledge.

Fossey also gave the gorillas their names, a habit she developed while living in the wild in close quarters with the animals. Like her peer Jane Goodall, who lived and worked with chimpanzees in the jungles of Tanzania, Fossey had become a world-renowned authority for her intimate observations of gorilla behavior.

“She was the first to habituate them and get them accustomed to a human presence, and to individually identify them,” says Tara Stoinski, president and CEO, and chief scientific officer of The Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International.

Like Goodall, Fossey began her study at the behest of the world-renowned paleontologist and anthropologist Louis Leakey. He hoped that study of primates would shed more light on human evolution.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f3/87/f387246e-08b5-4476-82fb-a16780201c63/ewn691web.jpg)

Much of Fossey’s focus—and the bullseye for many of the scientists who go to Karisoke—is gorilla behavior. When Fossey was observing the animals, only 240 or so existed in the forests of the Virunga, which straddle the eastern side of the Democratic Republic of Congo, northwest Rwanda and southwest Uganda. The eastern gorillas were on their way out, and Fossey knew it, says Stoinski.

As the gorillas died—either naturally or after being maimed in traps set by poachers to capture antelopes or other animals—Fossey started burying them, often where they were found, as it’s not exactly easy to move a 400-pound animal. She knew the bones might have a story to tell, but didn’t have the equipment on site to speed up decomposition. “To help the decomposition process, she’d bury them in shallow graves,” says Matt Tocheri, an anthropologist and Canada Research Chair in Human Origins at Lakehead University in Thunder Bay, Ontario, who has studied eastern mountain gorillas extensively.

Once the skeletal remains had decomposed, Fossey decided to ship some of them to the Smithsonian, the nation’s repository for important artifacts. “The fact that she recognized the value of these collections for science was an important innovation,” says McFarlin.

She sent the first skeleton—from “Whinny”—in 1969. It was not easy. The painstaking correspondence and coordination was carried out by letter, taking days and weeks to organize. Rwandan and American authorities had to sign off on every shipment—it was illegal to traffic in endangered animals after the 1973 Endangered Species Act became law.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e4/1b/e41b9510-7006-4a94-83c8-cab2e724347f/1280px-enter_the_silverback_8155790563.jpg)

Still, Fossey was committed to collecting the bones and sharing them with other researchers. But by the late 70s, she had grown tired of the bureaucratic hurdles. Poachers became an increasing obsession. On December 31, 1977, she experienced a severe blow: poachers killed her “beloved Digit,” a young male silverback she had grown especially close to, taking his head and hands. “I have Digit, who died terribly from spear wounds. . . buried outside my house permanently,” Fossey wrote in a January 1978 letter to Elizabeth McCown-Langstroth, an anthropologist and collaborator at University of California at Berkeley.

The letter revealed a woman on the edge. She was also reeling from what she claimed was an accusation leveled by Harold Jefferson Coolidge—a prominent zoologist who went on to help start the International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources—“of having gorillas killed simply to obtain their skeletal specimens.”

“Very few items of European—meaning white people slander—have hit me like this,” Fossey wrote.

She was livid. Fossey declared that she was done sharing gorilla skeletons. “They will not rot in the attic of the Smithsonian without care or study,” Fossey said, in the letter. “I will give up my life for my animals; that is more than that man ever did whilst ‘collecting’ for his studies,” wrote the scientist.

Fossey wrangled with her emotions and her benefactors and collaborators for the next few years, finally agreeing to one last shipment in 1979, which included Limbo and Green Lady. Those were the last skeletons Fossey sent to anyone.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9d/65/9d65e3fa-e2d4-4a14-a3f7-a6451539aed7/ticklish_gorilla_in_rwanda_at_the_volcanoes_national_park_290811211.jpg)

Fossey, born in San Francisco, was an animal lover who had no formal scientific training. Armed with an occupational therapy degree earned in 1954, but also a yearning to work with animals, she had explored Africa essentially as a tourist in the early 1960s, including a stopover to see Leakey at Tanzania’s Olduvai Gorge, and another to Uganda to see the gorillas that gamboled among the peaks of the Virunga mountains. By the time she encountered Leakey again at a lecture in America a few years later, she was already convinced that being with the gorillas was where she needed and wanted to be. Leakey secured funding for her, and in 1967, the 35-year-old Fossey established the Karisoke Research Center on the Rwandan side of the Virunga mountains.

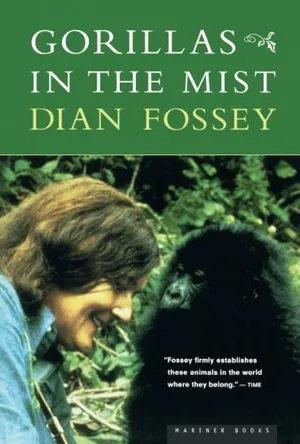

Eighteen years later, when she was found murdered in her cabin at Karisoke, Fossey had become a household name thanks to National Geographic, which supported and publicized her work. Her still-unsolved murder inspired Vanity Fair to send a reporter to Rwanda in 1986, resulting in a lengthy feature that offered theories—including that angry poachers had done her in—but no firm conclusions. In 1988, Fossey was the subject of a Hollywood biopic—adapted from her book, Gorillas in the Mist—with Sigourney Weaver in the award-winning role.

Fossey was a polarizing figure, who had driven away scientific collaborators and offended African helpers, but who also inspired a conservation and study movement that lasts to this day at that camp in Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park.

Her contribution to anthropology and the knowledge base about gorilla behavior is not a matter of dispute. “Her legacy is still very much present,” says Shannon McFarlin, a biological anthropologist at George Washington University who regularly visits Karisoke to conduct research. “It’s quite remarkable that the monitoring of these gorillas has been nearly continuous,” says McFarlin, noting that 2017 marks the 50-year anniversary of the establishment of Karisoke.

Having the remains from Fossey’s gorillas—a total of 15 complete skeletons and another 10 skulls—was invaluable to anthropologists, says Tocheri, who frequently made use of the collection during the near decade he worked at the Smithsonian.

Scientists seeking to understand human origins usually study the fossil record. But one can’t glean much about behavior from a fossil, or the relationship between bones and anatomy and behavior, says Tocheri. Hence, anthropologists look to our closest living relatives—primates, and Great Apes like gorillas and orangutans—to study those relationships and draw inferences on how it relates to human evolution.

Fossey was one of the first scientists whose collection offered a platform for researchers to put together the bones, the anatomy and the behavior. The collection, says Tocheri, “didn’t provide that information all at once, but it was the watershed moment that has led to what we now have.”

Fossey was more interested in behavior—she didn’t have the time or interest to study the bones. But years later, thanks to her efforts, scientists could now understand the context for why a bone might show a certain wear pattern, for instance.

“Adding that level of contextual knowledge is extremely important,” says Tocheri. He built on Fossey’s work to determine that eastern gorillas had a rare skeletal trait that was found to have no impact on how much time they spent in trees, as originally hypothesized, but it did allow scientists to further differentiate the species from western gorillas.

Context has also been critical for McFarlin’s work. She went to Rwanda in 2007, connecting with Tony Mudakikwa, the chief veterinarian for the Rwanda Development Board/Tourism and Conservation, who had an interest in recovering the mountain gorilla skeletons that had been buried after Fossey's death.

The Mountain Gorilla Veterinary Project—begun under a different name in 1986 as a result of Fossey's efforts—had been doing necropsies on gorillas that died, and would then bury them. This work, along with the gorilla observations and study by Karisoke researchers, continued after Fossey’s death, with little hiatus, even during the Rwandan civil war that led to the 1994 genocide and the instability that followed, according to Stoinksi of the Fossey Gorilla Fund.

The skeletons buried by Fossey and others, however, continued to lay at rest underground. The Smithsonian was home to the largest collection of mountain gorilla skeletons for scientific study until McFarlin, the RDB, the Mountain Gorilla Veterinary Project, and the Fossey Gorilla Fund recovered some 72 gorillas in 2008. Most were known to those who had buried them.

“We worked to establish protocols for what happens when new gorillas die in the forest and are buried, so we can more reliably recover all the bones and pieces,” says McFarlin. And because the animals are so closely observed, “when a gorilla dies, you usually know within 24 hours,” she says.

Bringing the skeletons to light marked a return to the promise that had been initially offered by Fossey’s shipments to the Smithsonian.

The skeleton collection—now representing more than 140 gorillas housed at Karisoke and managed in partnership with the RDB, the George Washington University, and the Mountain Gorilla Veterinary Project—has helped McFarlin and colleagues establish baseline data about the growth and development of mountain gorillas. That’s huge, because in the past, those milestones had been established by using data from chimpanzees kept in captivity—a far cry from the real world.

The collection has also “catalyzed new research on living gorillas,” says McFarlin. In 2013, she and her collaborators began taking pictures of living gorillas to compile a photographic record of body size, tooth development and other physical characteristics. The photographs will help “get a better picture of what normal development looks like,” she says.

Data from the skeleton collection, though enormously useful, could be skewed. For instance, a gorilla that dies young may have had a disease. Its measurements would not necessarily reflect a normal growth curve.

Not every scientist can go to Rwanda, however. For many, the Fossey collection at the Smithsonian is still the most accessible resource. Darrin Lunde, the collections manager for the mammal collection at the Natural History Museum, says 59 scientists visited the primate collection in 2016. About half came to see the Great Ape specimens, which includes Fossey’s gorillas.

Though static, the Fossey collection at the Smithsonian will play a dynamic role going forward, says McFarlin. Scientists will be able to compare skeletons collected by Fossey in the 1960s and 1970s to skeletons of gorillas that have died in the decades since, looking for differences over time. The Virunga gorillas have undergone significant change—with more animals occupying the same space, and an increase in human encroachment. Very little buffer exists between human and gorilla habitat. “You’re in someone’s farm one second, and in the park the next,” says Stoinski.

How will the skeletons of animals reflect these changes?

“The Smithsonian collection can be used in new ways to ask questions that haven’t been possible to ask in the past,” says McFarlin. Those questions will include delving into how environmental change or growth in human encroachment may have impacted gorilla developmental curves or whether they have certain diseases or not.

Stoinski says the Virunga gorilla population has rebounded to 480, doubling in the three decades since Fossey’s death. Another 400 eastern gorillas live in Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in Uganda. It’s not clear yet whether these gorilla populations—still considered critically endangered, which is one step above extinction in the wild—are actually growing, or staying stable, according to the IUCN.

Another group of eastern gorillas—Grauer’s gorillas (Gorilla beringei graueri), which live nearby in the Democratic Republic of Congo—are rapidly dying off. Poaching and “widespread insecurity in the region,” have pummeled the animals, the IUCN says. Recent surveys show that the population has declined from 16,900 to 3,800—“a 77 percent reduction in just one generation,” says the IUCN.

Karisoke researchers are replicating the Fossey model with that population, but it’s an uphill battle, says Stoinski. “If our protection of them isn’t improved, then we’re going to lose them.”

The work at Karisoke encompasses five generations of gorillas. People often say, “you’ve been there 50 years, how come you haven’t answered every question,” says Stoinski. But gorillas, like humans, are ever-changing, she says. “It’s literally like every day they do something different.”

“Objects of Wonder: From the Collections of the National Museum of Natural History” is on view March 10, 2017 through 2019.

EDITOR'S NOTE 3/21/2016: This article now clarifies that eastern gorillas include two subspecies—mountain and Grauer's. Fossey's studies focused on mountain gorillas. It also now correctly states that Tony Mudakikwa wanted to excavate gorillas buried after Fossey's death, and that, previously, the Smithsonian housed the largest, but not the only collection of mountain gorilla skeletons in the world. We regret the errors.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)