How Radio DJ Hoppy Adams Powered his 50,000-Watt Annapolis Station into a Mighty Influence

In post-war America, as advertisers discovered African American audiences, one local disc jockey drew top recording stars and a huge following

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5d/18/5d18c717-20f7-4bd3-a174-d873d68594b7/p150broadcastsetjn20143596web.jpg)

The plain tan wooden box, covered in wall paper, isn’t the fanciest thing in the expansive, new permanent exhibition, entitled "American Enterprise," opening July 1 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington D.C.

It may not compare to, say, George Washington’s Chinese tea set or William Ramsay’s 18th century ledger and desk, to mention two of the 600-object exhibit in the 8,000 square-foot Mars Hall of Business that anchors the museum’s new Innovation Wing.

But for regional R&B fans of a certain age, the humble carrying case is a veritable Pandora’s Box of memories, harkening back when WANN ruled the airwaves with 50,000 watts of power from 1190 AM in Annapolis, Maryland, identifying and serving the burgeoning African-American audiences well beyond the Eastern Shore.

There, disc jockeys like Charles “Hoppy” Adams were not just beloved personalities, but ambassadors of a culture, dominating not only on the airwaves but in numerous personal appearances and remote broadcasts, enabled by the special phone lines, wires and microphones enclosed in the tan case.

Not only would Hoppy Adams broadcast from local stores eager to serve the growing income of postwar African-Americans, he would host huge weekly events at the beach. Carr’s Beach, a private, segregated stretch of shore south of Annapolis, drew thousands of African Americans from miles around for its hassle-free seaside attractions, rides and slot machines.

Its Sunday afternoon concerts in the pavilion, hosted by Adams, drew the top recording stars of what was then called “race music”—from Lloyd Price to James Brown, Little Richard to Chuck Berry—and the Drifters, Coasters and Shirelles in between.

For Adams, who was a leading voice on WANN for more than 40 years, eventually becoming station manager, the weekly beach broadcasts were a highlight for not just the African-American neighborhoods, where you could effortlessly hear each week’s show, just walking down the street, blasting from stoop to stoop to passing car, but spread beyond to other audiences as well.

Radio signals weren’t hindered by the segregation era Jim Crow laws that affected beaches and rowhouses, so the vibrant sounds of “Bandstand on the Beach” broadcasts spread freely to other neighborhoods as well, helping make soul and R&B an American music beloved by a diverse audience of listeners, including young white kids who’d adapt it into their rock n’ roll.

But that was an unintended consequence of Adams presence in the community, solidifying an audience that previously was widely ignored by businesses and would later be catered to by the likes of BET network. And surely Adams had the look that would have taken him beyond radio, with sharp dressing, a pencil thin mustache and gracious manner that wasn’t just for show (he was a known philanthropist throughout his life).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/e8/ba/e8bace96-2b8b-44bf-b332-7cec986455a1/ac08000000010web.jpg)

Such bigger than life DJs set the tone for the young generations in America’s prosperous postwar era. In Baltimore, it was Fat Daddy who performed such a role, according to John Waters, the filmmaker who based his character in “Hairspray,” Motormouth Maybelle, on him.

“He was a huge musical influence on me,” Waters said of Fat Daddy. But he was quick to add, “You had Hoppy Adams in Annapolis—he was great!”

Born in 1926 to Ruby Loretta Queen Adams and Charles Walter “Happy” Adams Sr., in the small town of Parole, just west of Annapolis, the future radio star earned the nickname Hoppy from a bum leg, according to the Rev. John T. Chambers Sr., who took him under the wing as a young man and taught him how to cut hair.

Adams quickly moved from the barber shop to the taxi cab, though, eventually starting his own cab company. It was Morris Blum, who started WANN after World War II in 1946 as the city’s second radio station, and who hired Adams to spin R&B records five years later. Originally, Blum’s freewheeling radio format was “Bach to bebop,” but when that faltered, he turned to gospel and eventually aimed the station to the large and underserved African-American audiences.

With that he helped fuel what author Andrew W. Kahrl called a perfect storm with a new consumer group, advertisers lining up to serve them, and an array of stars who’d head to Annapolis wanting to get airplay on the influential station who would gladly play the Sunday afternoon shows at Carr’s Beach.

“With his boundless enthusiasm and exuberance, he quickly attracted a large following of listeners and became the face of the station,” Kahrl says of Adams. “Fledging black-owned record labels in Baltimore and other mid-Atlantic cities competed for the chance to have WANN broadcast their latest singles.”

With 50,000 watts of power, the station’s influence was felt from Delaware to D.C., and sometimes as far west to Ohio. And thousands jammed the pavilion at 3 p.m. sharp for the shows from artists like Ray Charles, Dinah Washington, Otis Redding, Ike and Tina Turner, Jackie Wilson and Stevie Wonder. Some 70,000 were logged trying to get to a 1956 Chuck Berry performance there.

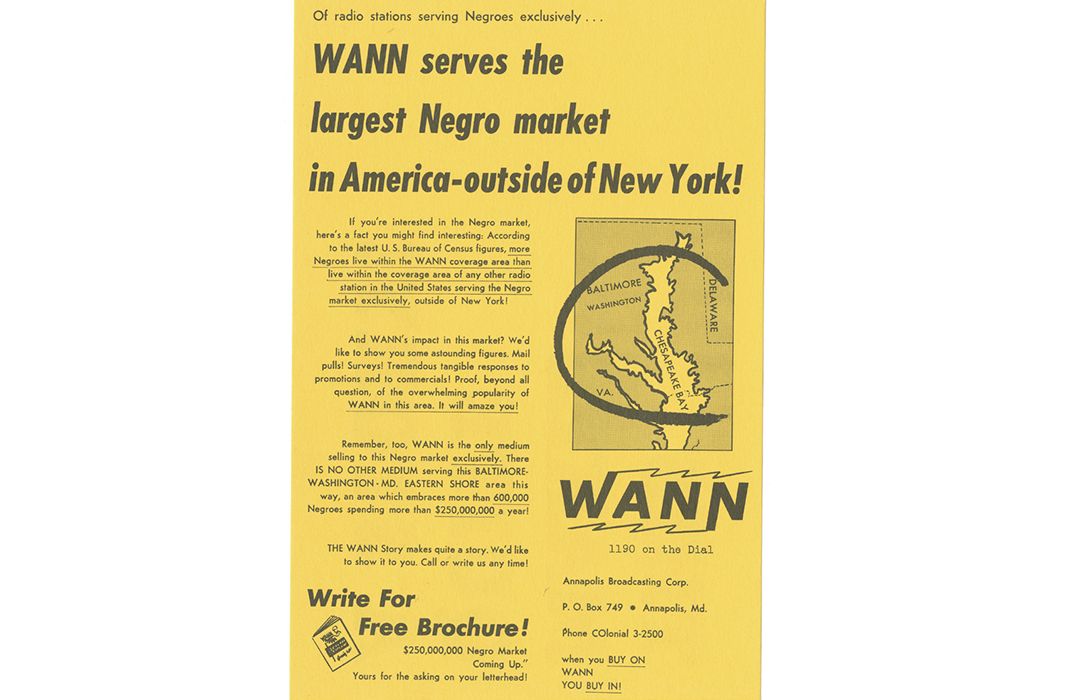

The station took note of this huge audience and the influence it had in attracting it.

A flier from around 1950 boasts, “More Negroes live within WANN coverage area than live within the coverage area of any other radio station in the United States serving the Negro market exclusively, outside of New York.”

Driving the point home, it shifted to capital letters: “There IS NO OTHER MEDIUM serving this BALTIMORE-WASHINGTON-MD. EASTERN SHORE area this way, an area which embraces more than 600,000 Negroes spending more than $250,000,000 a year!”

The flier is part of the cache of items from the WANN heyday donated to the Smithsonian after 1190 AM abruptly switched to a country music format in 1992.

Kathleen Franz, associate professor and director of public history at American University and one of four curators to work on the “American Enterprise” exhibition, said the WANN collection includes boxes and boxes of 45s and albums, several photographs including performers like Sarah Vaughan and Frankie Lymon appearing before packed beach audiences, and several station banners.

There is also a gold record on display that was sent from the Stax label, thanking the station for its part in making the Staple Singers’ “If You’re Ready (Come Go With Me)” a hit in 1973 (“Thank you for Going with Us,” the plaque says). Also on display are a couple of identifying pins from other WANN DJs, The Deacon and Pitt.

Franz, a co-author of the American Enterprise catalog, said it was important to show the artifacts of the Annapolis station alongside bigger, better known national companies, to show the vitality of African-American broadcasting serving its audience in that era (She makes a similar point in the exhibition regarding Spanish-language broadcasting and Latino market advertising).

“Although there was a growing awareness of African Americans as a market force in the early 20th century, and even a handful of market surveys on black consumer preferences, it wasn’t until World War II that national businesses began to take seriously the buying power of African Americans,” she writes in catalog.

Radio was a good way to reach specific audiences at a better price than magazines or then-new television, she said. While the first black radio station started in Chicago in 1929, by 1955 there were 600 radio stations catering to African Americans.

The key to their success in many cases were individual personalities such as Adams, whom she says “embodied the complex threads of black-oriented radio with his respect for the community, its commerce, its music and its burgeoning teen culture, all of which defined the music at WANN.”

Adams, for his part, eventually became executive vice president of WANN and was elected to the Maryland D.C. Delaware Broadcasting Association board of directors in 1976.

He died in 2005 at the age of 79. Carr’s beach has long since closed and become a private development. A legacy of the period continues, however, not only in the exhibition, but through the work of the Hoppy Adams Foundation in Annapolis which just began its annual fundraising efforts for its scholarship drive, “to fulfill the vision of Hoppy Adams, which is to ensure that a positive atmosphere is created where students experience a sense of belonging, positive self-esteem and inspiring them to see the positive impact they can have in their community with our assistance.”

“American Enterprise” opens at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington D.C. July 1, 2015.

American Enterprise: A History of Business in America

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)