Don Draper’s Gray Suit and Fedora Are Among “Mad Men Props” Donated to the Smithsonian

Members of the television show’s stellar cast, along with director Matthew Weiner, dropped off some significant “Mad Men” swag

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/06/2e/062e8f3a-9358-4126-9ff6-9f3b993cfacc/draperweb.jpg)

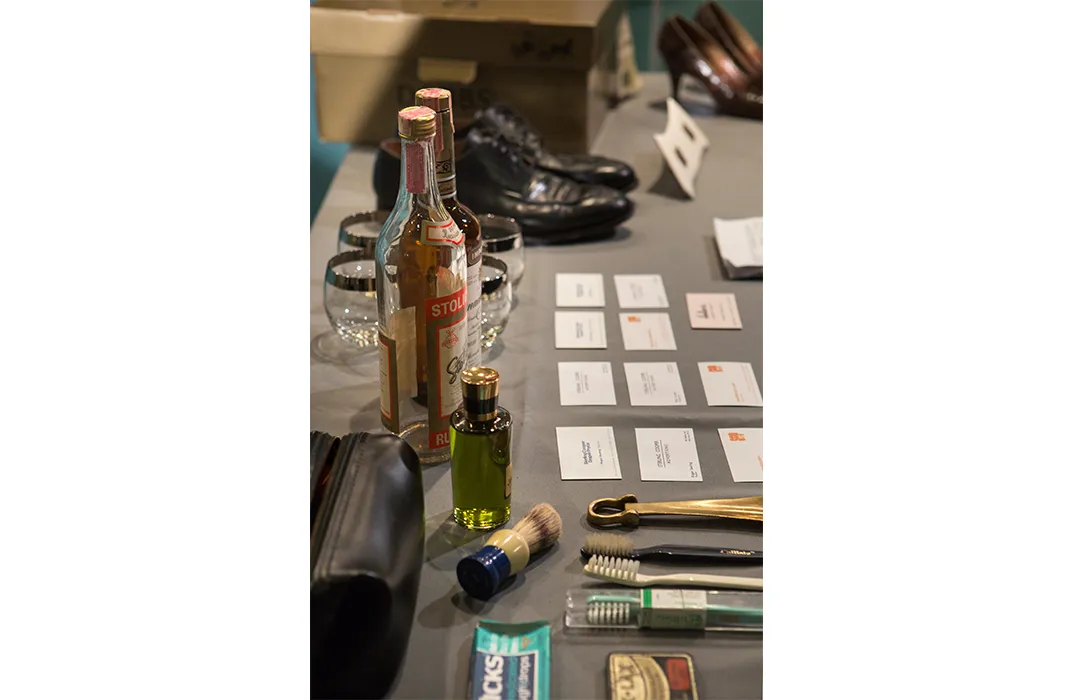

The vintage liquor, tumblers and cigarettes were all out Friday morning, but it wasn’t for another meeting at Sterling Cooper.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History was displaying some of the iconic items from “Mad Men,” the acclaimed series on advertising in the 1960s that is soon ending its run.

“They say all good things come to an end, and all great things come to the Smithsonian,” AMC president Charlie Collier, said at a packed presentation ceremony, attended by show creator Matt Weiner and three of the show's cast members: Jon Hamm, John Slattery and Christina Hendricks. “We really are humbled that this series will live here in perpetuity as a piece of American popular culture,” Collier said.

“Like most of America, I visited the Smithsonian as a child,” said Weiner. “When I heard about this possibility, I said to my wife, ‘Oh my god, we’re going to be on the field trip.'”

But not for a while. The more than 50 artifacts belonging to the fictional ad man Don Draper, his business associates and family, including props, clothing and drawings, won’t be on display to the public until a planned exhibit on American culture in 2018, although some of the items may be seen as new acquisitions, especially to juxtapose with actual advertising items of the 1960s, in the permanent exhibit “American Enterprise” set to open July 1.

The most striking examples of the "Mad Men" donations are the meticulous period clothing, including the memorable yellow house-dress Betty Draper wore in Season 1, and the blue floral apron she wore with it. But there are also a lot of accessories, including watches, sunglasses, a brass shoehorn, a travel alarm clock and the accessories bag that Don brought on his trip to Hawaii with his second wife, Megan.

There are two bottles of liquor—a Canadian Club and a bottle of Stolichnaya from the period, along with glass tumblers and two packs of cigarettes—Lucky Strike and Salem. “The fuel of ad men,” said Dwight Blocker Bowers, entertainment curator at the museum.

A full script of the season finale from the first season, titled “The Wheel,” features an alternate ending (where Don actually does go to Thanksgiving dinner at Betty’s father’s house instead of staying home). Several of the items donated are already on display at the Museum of the Moving Image in Astoria, New York, including Don’s full office bar cart, which will come to the Smithsonian later.

Because the actors have been on a whirlwind of openings and events in advance of the last set of “Mad Men” episodes (starting April 5), they didn't even say a few words, though they posed with some of the donated drawings of their costumes. Hamm, bearded now in a way that his clean-shaven Madison Avenue character never would have been, stood near his donated grey suit and fedora for photographers.

They had just flown in that morning from New York and were immediately on their way to Los Angeles for another event, Bowers said.

Still, there was enough Hollywood glamor to go around for a morning photo-op, with some museum staff going in for selfies with the stars. The “Mad Men” items will take their place alongside more than 7,000 objects in the entertainment collections at the American History Museum, which includes the original Howdy Doody and Kermit the Frog puppets, Archie Bunker’s armchair, Fonzie’s leather jacket and Jerry Seinfeld’s puffy shirt.

Items on display for the "Mad Men" ceremony Friday included a small bottle of Jade East cologne, a box of Vick’s cough drops and a tin of Ex-Lax.

“What I love about these objects being here is that they are for the most part the actual objects, they are not recreations,” Weiner said. In that way, the show had done a lot of the curatorial work about authentic everyday items of the '60s for them, Bowers said.

But they also created detailed business cards and checkbooks, even when they weren’t featured prominently on the screen. Some of those gave a hint of Draper’s character trajectory, from salesman at Heller’s Furs to his role at various permutations at the firm that began as Sterling Cooper (we also learn from the cards the specific addresses of the fictional companies—405 Madison Avenue and 1271 Avenue of the Americas—as well as the Manhattan addresses of Draper, gleaned from his checkbook: 104 Waverly Place, Apt. 3B and 783 Park Ave., 17B).

“We’re glad we saved these things and recreated these things. So much of it was thrown away that it was fun to try and recreate a check stub,” Weiner said. Bowers said acquiring the works from “Mad Men” had been in the works for about a year. He said it was important to make contact with shows while they’re running because “the minute they wrap, the artifacts go to the winds. So we had the opportunity to pick and choose while everything was still assembled.”

He added that “Mad Men” was a clear choice for securing its props and ephemera at the Smithsonian. “It raised American cultural history, and the particulars they would do to reconstruct the era, right down to the labels on the liquor bottles, that are absolutely authentic to the 1960s.”

The donation wasn’t the first interaction with the show. Several years ago, Smithsonian deputy director Susan Fruchter said, someone from “Mad Men” called with a question: How was a telegram delivered in 1963? “We actually knew that,” Fruchter said. A Western Union pamphlet from the era was produced.

“That particular scene didn’t make it in,” she said, “but it’s an example of how the story lines explored in television intersect with larger themes and issues in American life.”

Likewise, Fruchter said, the “Mad Men” artifacts will create “a bridge between the fictional and the historic.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3a/93/3a9338d5-2362-4053-b0a6-2ec6cb04f22d/et20151888web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/23/94/2394c122-2311-4f4a-aebe-a326131e3476/jn20155642web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9b/d5/9bd592e9-3a6c-46b0-9c16-3fe9261574ef/rws201504792web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)