A Double Header for Béisbol Lovers

Out of the barrios, into the big leagues came Clemente, Abreu and Martínez. Now the unheralded are All-Stars in this expansive show

:focal(685x114:686x115)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/de/63/de638c3d-5f2c-4f06-9e61-12f69ea10e00/clemente.jpg)

Baseball is thought to have been introduced to the Caribbean and later Latin America by the children of wealthy Cubans who were sent to the United States in the 1860s for schooling. Returning home with enthusiasm for the new sport, as well as lugging back equipment, they spread the gospel of baseball across the islands, and then to the Dominicans, Puerto Rico, Venezuela, Mexico, Colombia, Brazil and throughout South America.

More than a century and a half later, fully 30 percent of Major League Baseball rosters are Latino and the game would be very different without their participation.

A new exhibition at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History “¡Pleibol! In the Barrios and the Big Leagues/En los barrios y las grandes ligas” celebrates the big-league successes and renown stars like Roberto Clemente to Fernando Valenzuela to Pedro Martínez and Anthony Rendon.

But the show on view in the museum’s Albert M. Small Documents Gallery also pays heed to women in the sport, from half-remembered stars of the women’s league to the owner of today’s Colorado Rockies, Linda Alvarado, whose quote is written on the walls: “Latinos have changed baseball, period.”

¡Pleibol! En los barrios y las grandes ligas

Stories and objects included in this volume brings our seemingly disparate pasts and present together to reveal how baseball is more than simply a game. The history of Latinos and baseball is this quintessential American story.

Curator Margaret N. Salazar-Porzio says she spent six years on the project. She began not with the biggest names, but in small community meetings where information was shared about individual Latino leagues of baseball enthusiasts. She traveled to Southern California, Florida, rural Colorado, Wyoming and Nebraska where she discovered the stories of players in the Spanish Colony league, who built up their pitching arms by whacking at sugar beets with big knives all day.

“The community-driven aspect of it is what I’m most proud of,” she says. In Puerto Rican communities of New York City, stickball was king, and a bat, cobbled together from a broom handle and a bicycle inner tube is on display alongside the smaller Spalding ball they still use.

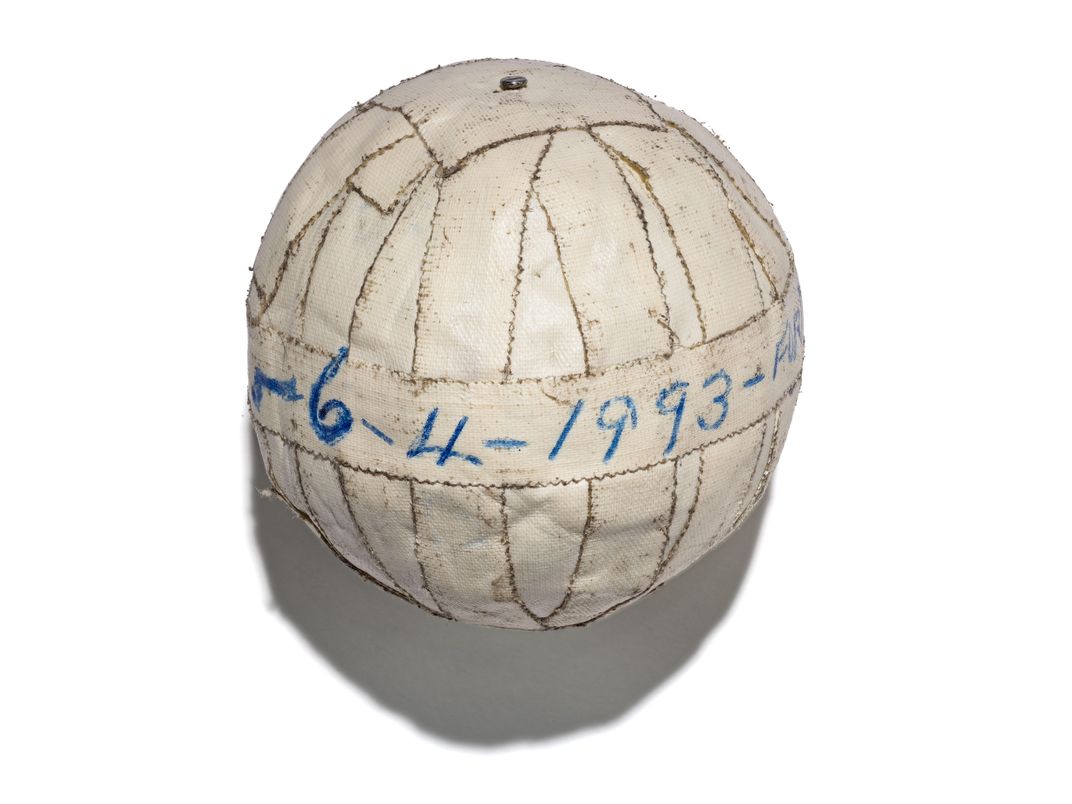

It was tough to find examples of balls or gloves people used because they were so worn out, Salazar-Porzio says. There is a handmade ball from Cuba made from wrapping tape around a solid core. A glove donated by a family from La Puente, California, was stitched and restitched over generations (it came with extra lace and needles just in case). In the 1980s fast-pitch softball player Chris González received a pair of game-worn cleats from the equipment manager of the Kansas City Royals and wore them for the rest of his career even though they were two sizes too small; he gifted them to the museum.

In a film that accompanies the exhibition, a Major League star shows how folded cardboard was commonly used in place of leather gloves in the fields (surviving examples of those, understandably, didn’t survive).

As Salazar-Porzio put together the show after visiting 15 states and Puerto Rico, themes emerged. “Over and over again, I would hear these stories about the love of baseball, people’s memories of the game, how baseball and softball really helps local communities grapple with racism and discrimination,” she says. “It was really trying to figure out with them how to talk about this history.”

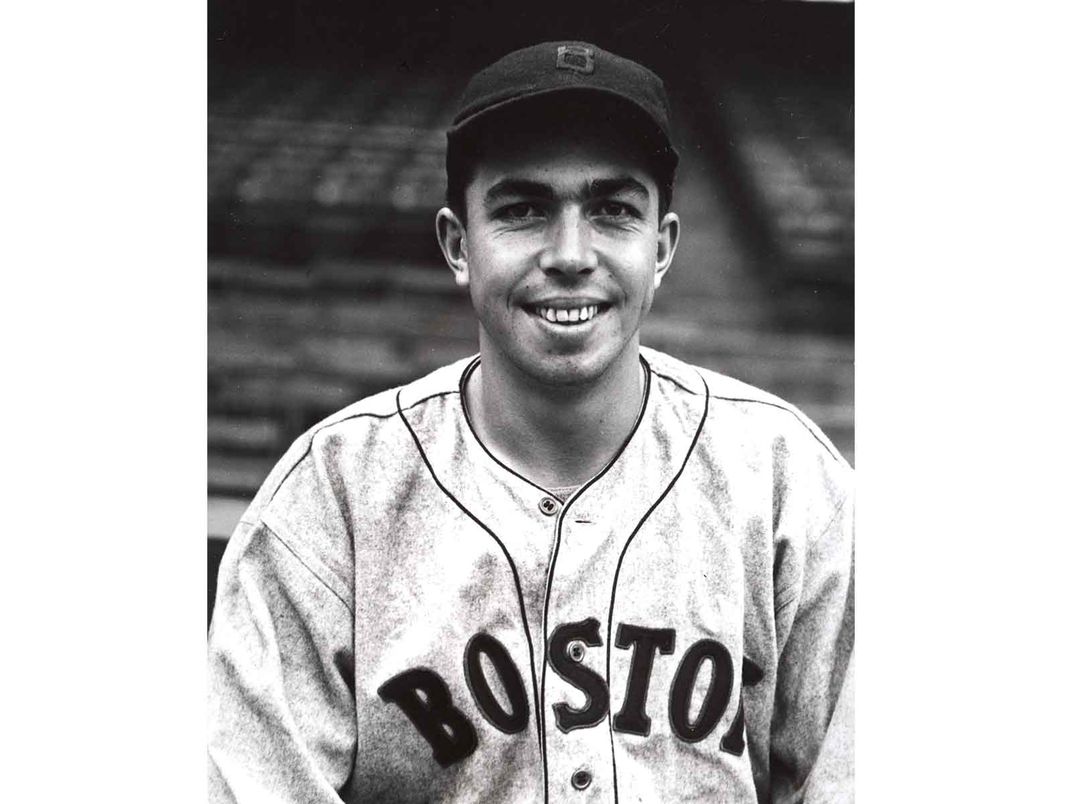

Discrimination kept even the best players like Martín Dihigo, José Méndez and Cristóbal Torriente from playing professional. Baldomero “Mel” Almada was the first Mexican to play in the major leagues. Between 1933 and 1939 he would play center field for the Boston Red Sox, the Washington Senators, the St. Louis Browns and the Brooklyn Dodgers. “We witness how some players like Ted Williams kept their Mexican ancestry hidden,” wrote historian Adrian Burgos Jr in the show’s catalog. “Alamada, a Mexican native who was raised in Los Angeles, did not.”

Before Jackie Robinson broke the color line, a few franchises sought out Latino players, “as long as the individual player,” wrote Burgos, “was not clearly black.”

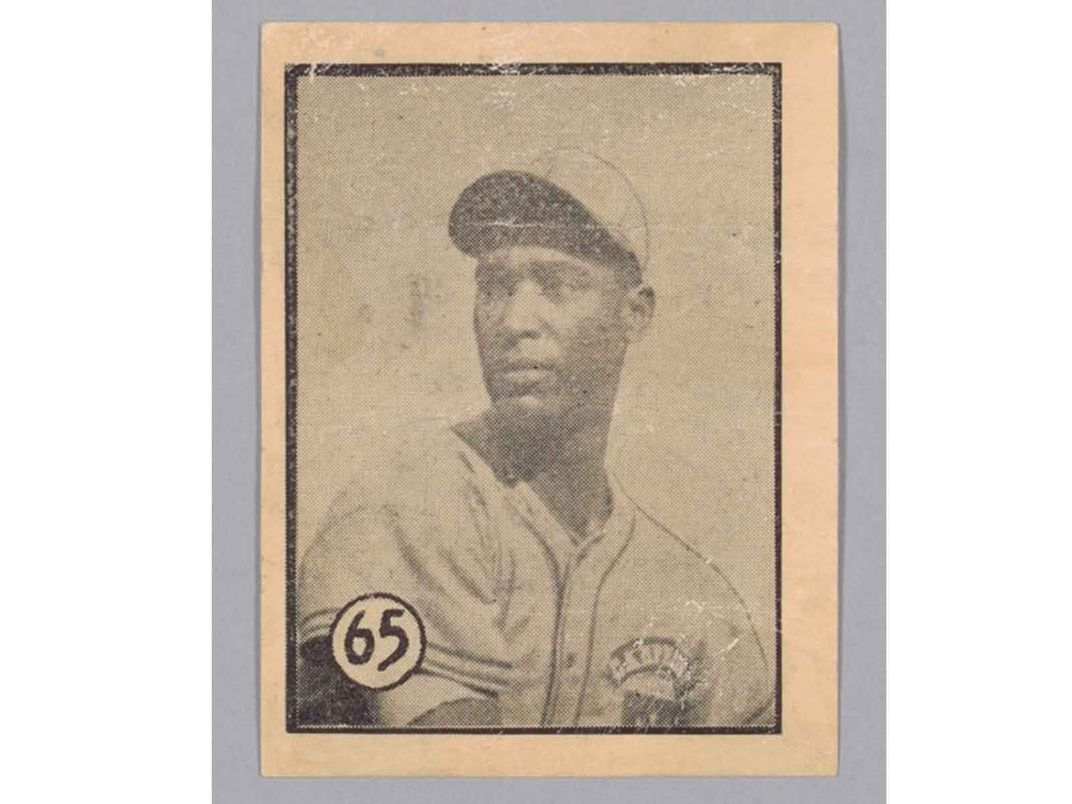

The Negro Leagues welcomed Latinos regardless, looking only for the talent needed to fill their ranks. The Cuban Stars of the Negro Leagues hired second baseman Dihigo, who could play any position, including pitcher; he would be enshrined in the National Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown. Renowned throughout Latin America (he’s also in the halls of fame of Cuba, Mexico, Venezuela and the Dominican Republic), he’s not as well remembered as players in the majors whose stellar stats were similar.

The acceptance was reciprocal, Salazar-Porzio says, as some U.S. players in the Negro League also found a home playing in international leagues, such as the former Homestead Grays star Buck Leonard, who played in the Mexican League from 1951 to 1955, when he was in his 40s. The 1951 bilingual contract (for $6,390) is on display.

Latino teams also played in leagues alongside Japanese players, similarly exiled from the majors, as exhibited in some saved scorecards on display from the 1954 Eagles of Mitchell, Nebraska. The mixing of cultures is celebrated in a series of vivid paintings on display from Ben Sakoguchi, depicting teams in the colorful tones of orange crate art common in the rural West.

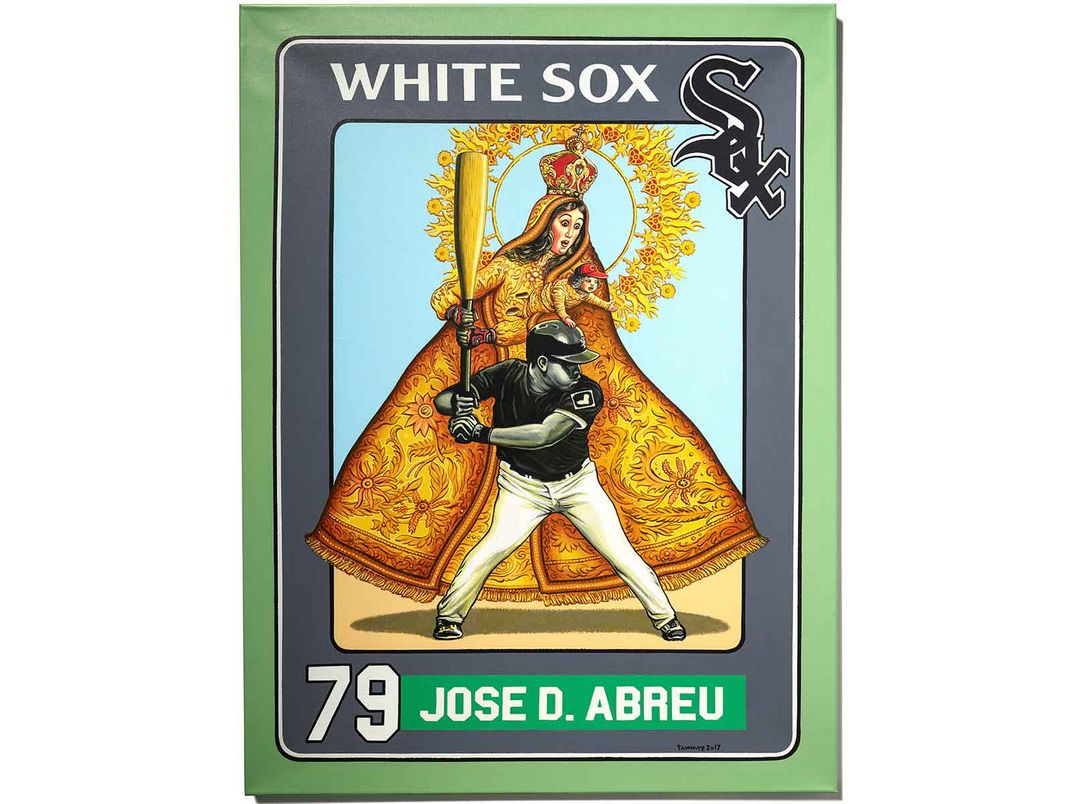

Other art in the show includes a painting by Reynerio Tamayo in the style of a baseball card for Jose Abreu of the Chicago White Sox but protected by the Cuban patron saint. “Oh my gosh, it’s such a great painting,” Salazar-Porzio says. “It depicts how religion, and immigration and baseball are intertwined in Cuba in particular, through the story of Jose Abreu, who had to leave his 2-year-old son at the time to play in the major leagues.”

The decline of Cuban players in the majors due to political concerns opened the door for Dominican stars who have proliferated in recent years, including the trio of Red Sox stars Manny Ramirez, David Ortiz and Pedro Martínez.

To be sure, some of the art in the exhibition is homemade by players or their family members, leading to some unusual and singular artifacts, such as the Life magazine scrapbook assembled by Leopoldo “Polín” Martinez with posted articles about his baseball career in Mexico, California and Texas. While many stars maintained scrapbooks, pasting it in a magazine provided them with the illusion of mass publication fame that eluded so many.

Women played an unsung story behind the scenes, as well, Salazar-Porzio says. “They’ve given their time, they’ve given their talent, they’ve given their treasure in support of communities, from players to fans, mothers, daughters, they made their own teams, they sewed patches, they made the uniforms, they cared for kids while their husbands or brothers or fathers could play, and they were entrepreneurs—they sold concessions and food and fed the players.”

Some also rose to prominence, from Colorado Rockies owner Linda Alvarado to Jessica Mendoza, part of the Gold Medal winning Team USA softball team in 2004, who became the first woman sportscaster to call a Major League game on ESPN in 2015.

Of the big-name players, Clemente, who Salazar-Porzio calls the “most well-known and revered Latino baseball player in all of U.S. history,” spent 18 years with the Pittsburgh Pirates, who was revered for often returning to Puerto Rico to mentor young players and died in the act of philanthropy, in a plane crash carrying supplies to Nicaraguan earthquake victims on Dec. 31, 1972.

A Mexican hero credited with growing the Latino audience at Dodger Stadium from 10 percent to more than half, is pitcher Fernando Valenzuela. But also credited with growing the Latino audience was Spanish-language sportscaster Jaime Jarrín, who began calling games for the Dodgers since their first season in 1959 and at 85, is still doing so, now alongside his son Jorge Jarrín. As such, he’s the longest tenured active broadcaster in baseball.

“He gets overlooked because he’s a broadcaster, but has made such an impact in Spanish language broadcasting and baseball broadcasting,” Salazar-Porzio says of Jarrín.

Dodgers Stadium had to do a lot to mend relations with the Latino community since it was their community Chavez Ravine that was razed to build the stadium that opened in 1962.

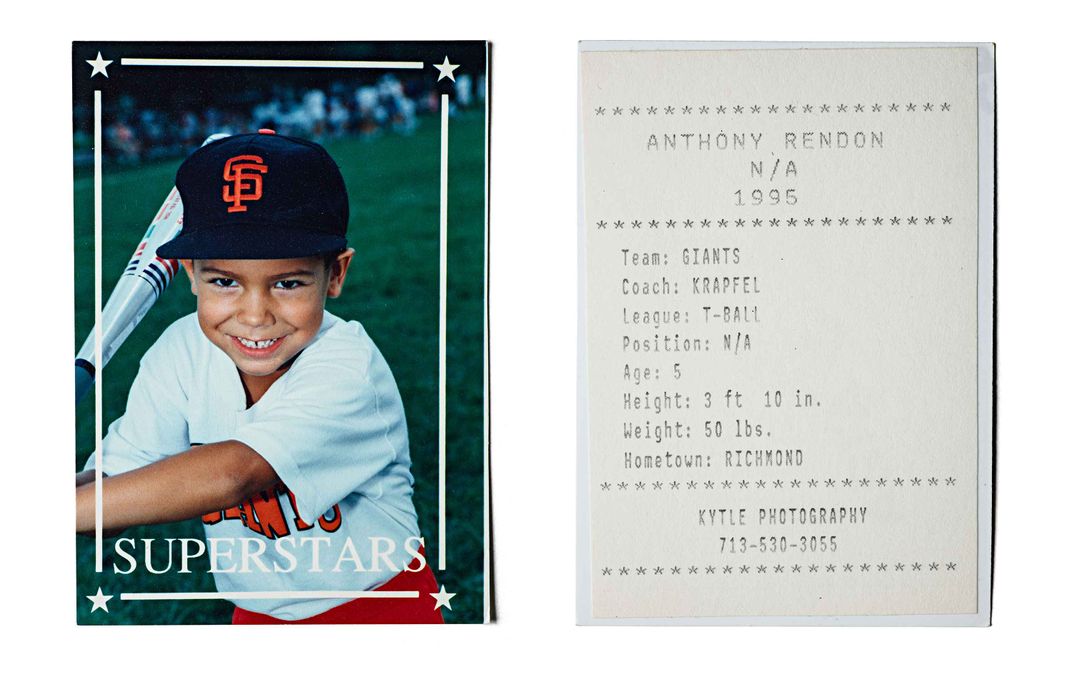

Locals in Washington will relish the representation of one of its 2019 World Series heroes, Anthony Rendon, whose Houston YMCA baseball card from 1995, when he was only 5, is included—as is his Nationals World Series bobblehead, earned when he was 25.

Rendon was no longer with the Nationals when “¡Pleibol!” was originally scheduled to open last year. A free agent, he had signed with the Los Angeles Angels a few months earlier. The original date for the exhibition opening—April 2020, has been delayed twice by the pandemic, Salazar-Porzio says. Rescheduled to open during baseball’s postseason last October, it had to be delayed again as museums closed up again.

But she’s happy with the new date, July 2, 2021. “It’s a good day,” she says. “It’s right around the time of Independence Day, it’s baseball season, it’s close to the All-Star Game. I feel like we’re in good company now. I feel like this one will stick, for sure.”

“¡Pleibol! In the Barrios and the Big Leagues/En los barrios y las grandes ligas” opens July 2 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. Admission is free, but reserved time-entry passes are required and can be obtained online. A live streamed virtual opening is scheduled for July 9. A traveling version of the show is currently on display at the El Pueblo History Museum in Colorado through August 1, one of 15 cities it will visit through 2025.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)