These Dramatic Photos Reveal the Soul Behind the Day of the Dead

New Mexican Photographer Miguel Gandert allows his subjects to narrate their own story

:focal(356x96:357x97)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/14/57/14577d61-806c-4995-9562-47666c99e6e9/dia-del-la-m.jpg)

On the subject of cameras and film, the late art critic John Berger once said: “What makes photography a strange invention—with unforeseeable consequences—is that its primary raw materials are light and time.” Berger was lyrically revisiting the birth of film technology, an occurrence that must have been seen as perplexing magic, perhaps a thieving of souls or some doubtful prefiguring of Einstein theory.

The early inventors had no idea what they were getting us into. They hadn’t a clue the innumerable uses photography would be put to, or the depths of meaning one could apprehend from a single image of a French villager’s cottage, or a Prussian couple standing in a rocky field. A strip of negatives was made of silver halide, and those crystals were irreparably transfigured by the reflected light that struck them and for how long. But the effects of time on a frame of film aren’t limited to the movement of the shutter.

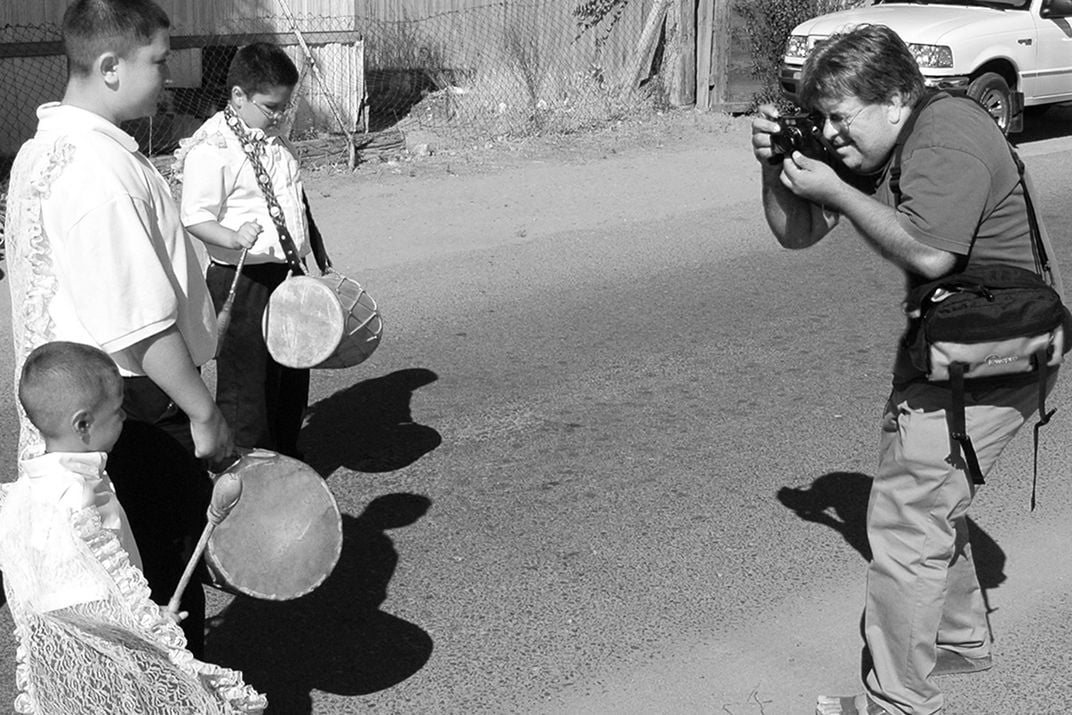

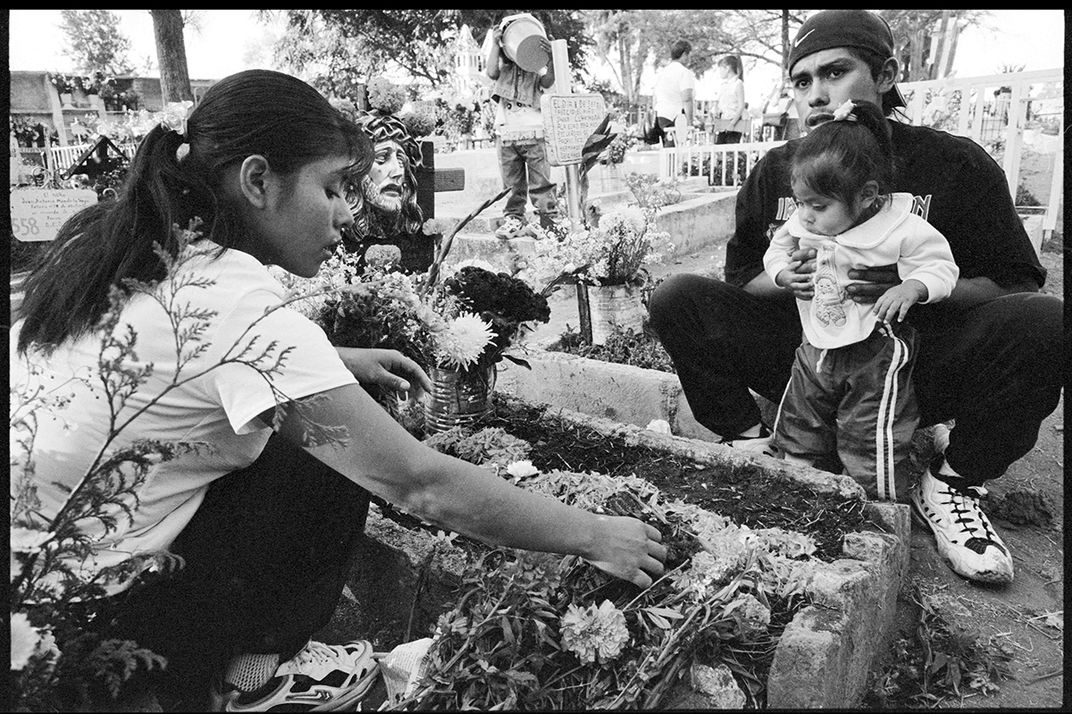

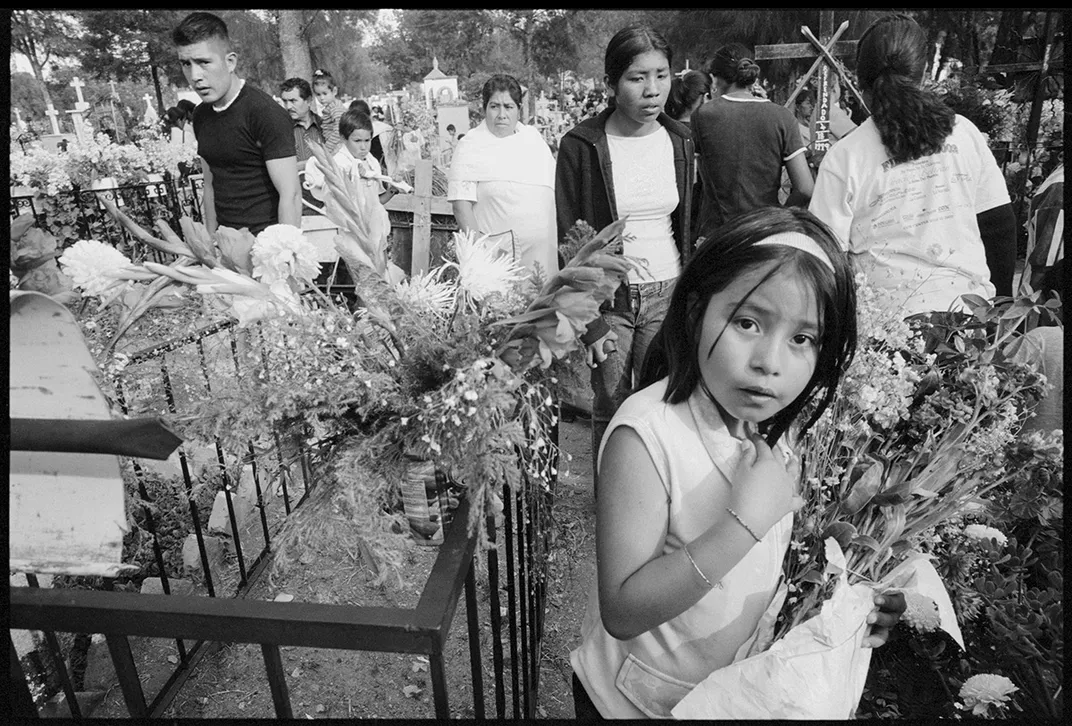

The eye of New Mexican photographer and ethnographer Miguel Gandert’s camera refuses to roam, but engages his subjects directly. He often packs the frame so full of personal and cultural information that the image transcends the time and light it took to make it, becoming instead a visual journey through his subject’s life.

Folklife curator and folklorist Olivia Cadaval observes that Gandert’s work is “all about social action.” Since the 1970s, through early fieldwork and the production of his numerous books and exhibitions, he has immersed himself in the lives and communities of many, from AIDS victims along the U.S.-Mexico border, to boxers and wrestlers, to penitentes involved in religious rituals of Indo-Hispano origin.

“Advocacy is the foundation of all his work,” Cadaval says

Gandert’s images are startling for their intentionality and for the connection they evoke between photographer and subject, involving direct eye contact and a healthy amount of personal risk. His work has been shown in many museums including the Whitney, and collections of his work are housed at Yale University and the at the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

“Ever since the beginning, I’ve wanted my pictures to look back at people,” Gandert says. “I make them in collaboration with those I photograph. These are peoples’ lives, and I ask my students—do you want to be a spy or a participant? If I’m close, then I can’t be invisible.”

Gandert still carries a film camera, a Leica Rangefinder M6. He shoots Tri-X Pan, the same black-and-white film he always has. “I was in the museum at Yale looking at old Roman sculptures, and it came to me that like those statues, actual film is an artifact too, present at the moment of a photograph’s creation,” he reflects. “Maybe I’m a romantic, but it’s grains of silver. It’s alchemy. Pixels are just. . . nothing.”

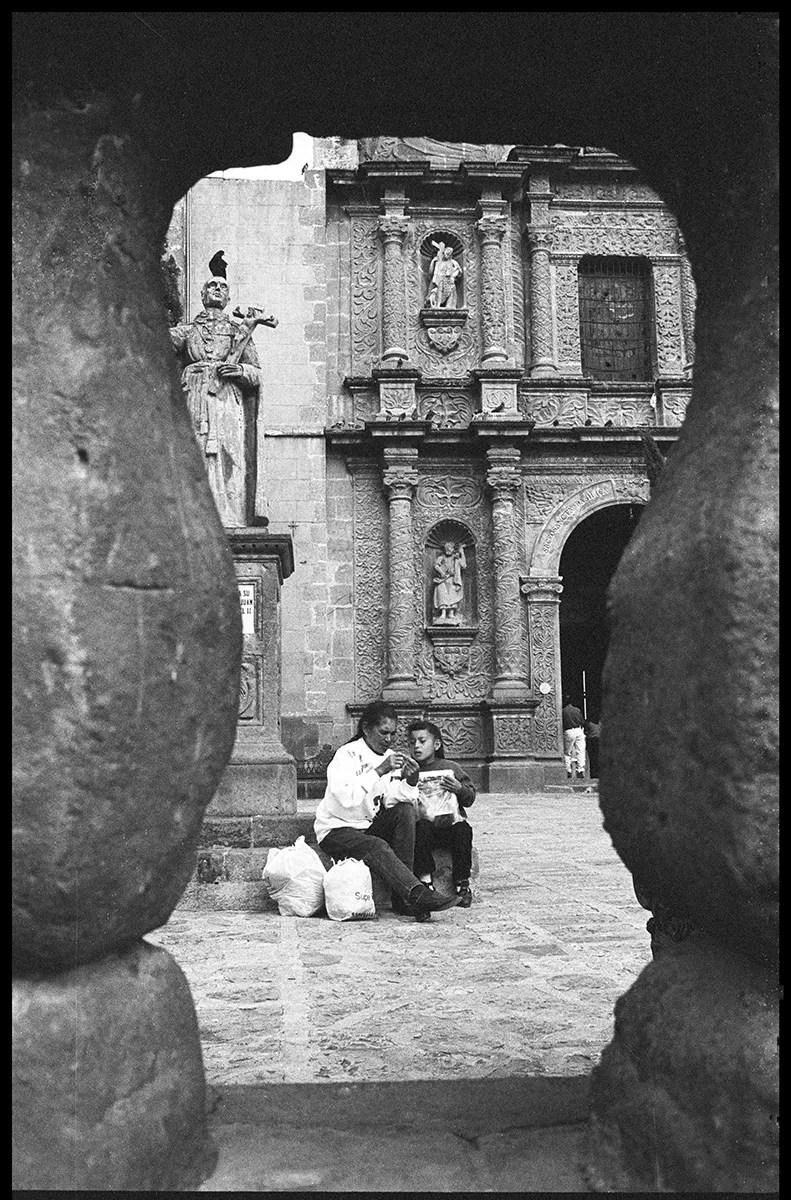

In the fall of 2008, Gandert was teaching a workshop in Valle de Allende, Mexico, the newish name for an old colonial city founded by Franciscans in the mid-1500s.

“Early that morning, I did what I always do when traveling. I pulled out one camera body and one lens—as I get older, my camera bag gets lighter—and I went out in search of a cup of coffee and something interesting going on.”

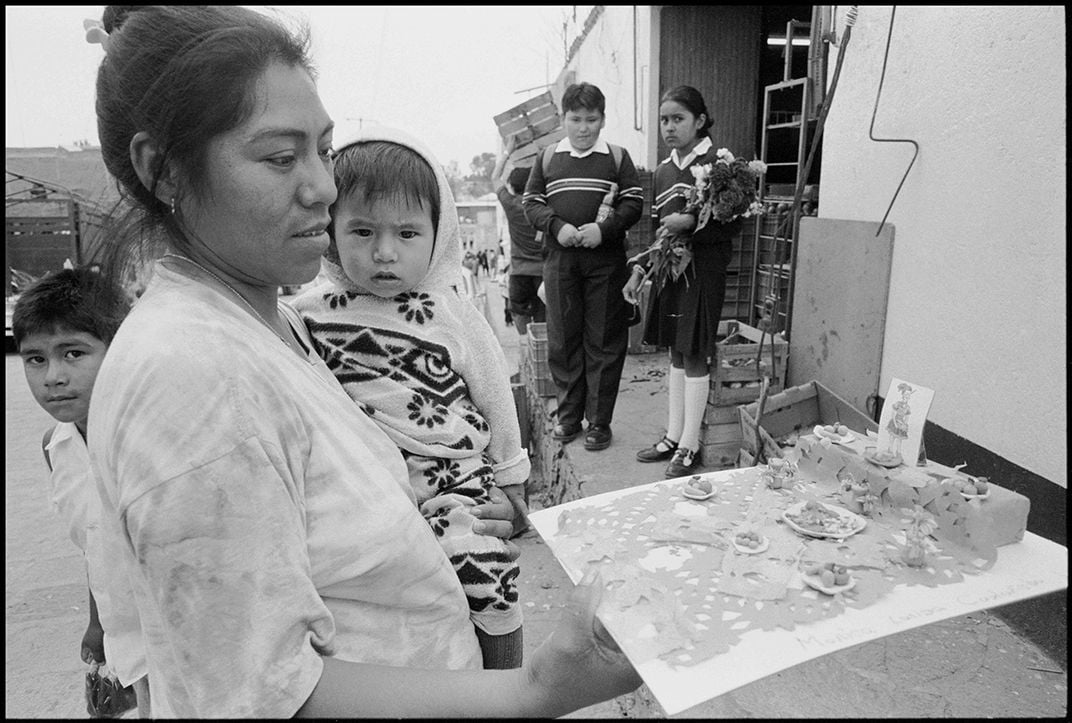

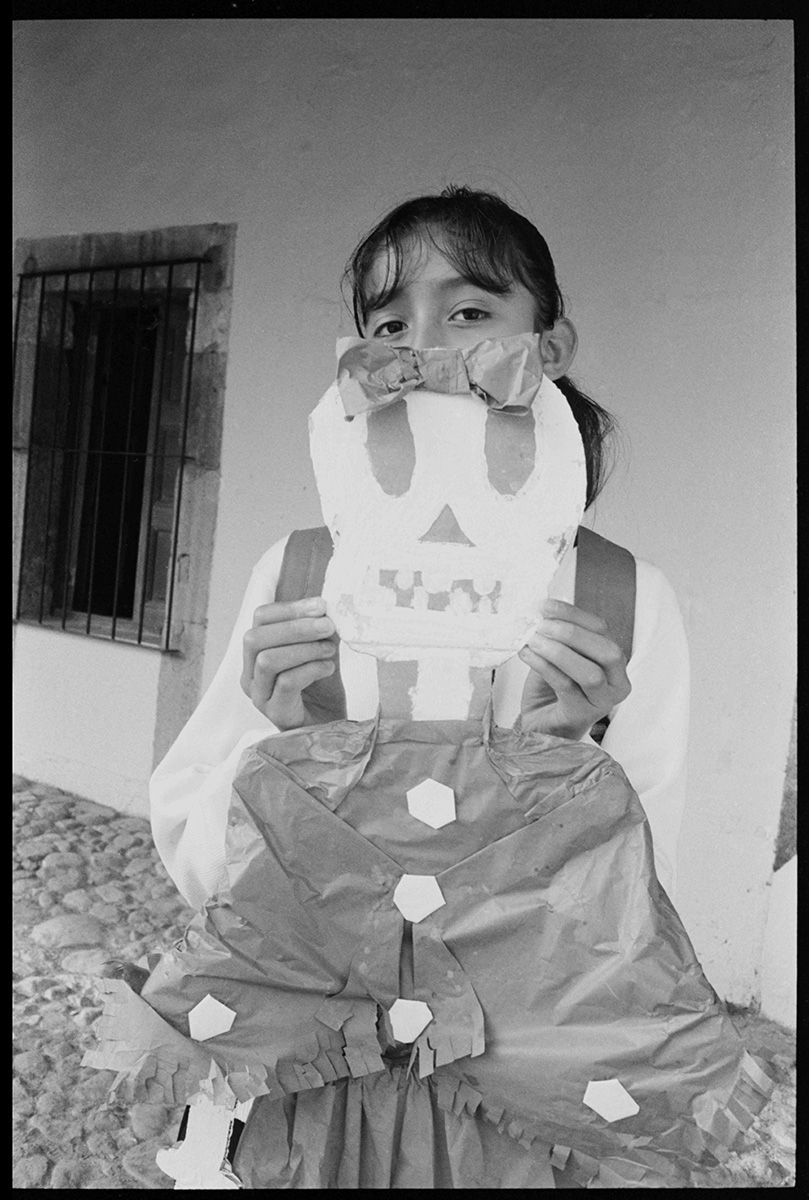

Just off the main street, he found himself amid a bustle of families and school children. The date was October 31, by tradition, Día de los Angelitos, and known in Europe and elsewhere as All Hallows’ Eve. On this day, children make altars to honor those who were taken too soon, children close to them who had died. The Day of the Little Angels is the first of a triad of days best known for the last, Día de los Muertos, or the Day of the Dead.

On that day, families carry offerings to the gravesites of the departed. Marigolds are brought wrapped in paper, along with the favorite food and drink of deceased loved ones, and even sometimes favorite possessions. Across the hours, past and present align as old and new stories are swapped and the dead invited to share in the feast and song.

Gandert was impressed by the assignment teachers had given students: to create altars for Día de los Angelitos. “This was culturally relevant homework—so they won’t forget!”

On the third day in Valle de Allende, he visited a cemetery alongside local people who had come to make altars of the gravesites. Author Jorge R. Gutierrez wrote about the emotional resonance of Día de los Muertos: “as long as we remember those who have passed away, as long as we tell their stories, sing their songs, tell their jokes, cook their favorite meals, THEN they are with us, around us, and in our hearts.”

Many say Gandert’s work strikes the same chord, that his close collaborations in the lens free his subjects to narrate their own story and reveal their lives on their own terms. Through the creation of his photographic artifacts, he invokes living history.

“Over time I’ve come to see myself as the guardian of the pictures, not necessarily the creator,” Gandert says. “It’s my responsibility to get the images out into the world because I believe people have given me a gift that I want to share. The meaning of the pictures sometimes changes as I share them with scholars and the subjects. New scholarship emerges. New information comes available. I’m always to trying to understand their narrative, their meaning. It’s my responsibility.”

A version of this story appeared on the online magazine of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife & Cultural Heritage.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/endnotes-gallery-19.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/endnotes-gallery-19.jpg)