During World War I, Many Women Served and Some Got Equal Pay

Remembering the aspirations, struggles and accomplishments of women who served a century ago

:focal(985x580:986x581)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1b/2b/1b2bf299-3630-427e-9167-9aacd6f8d487/4433_p_002.jpg)

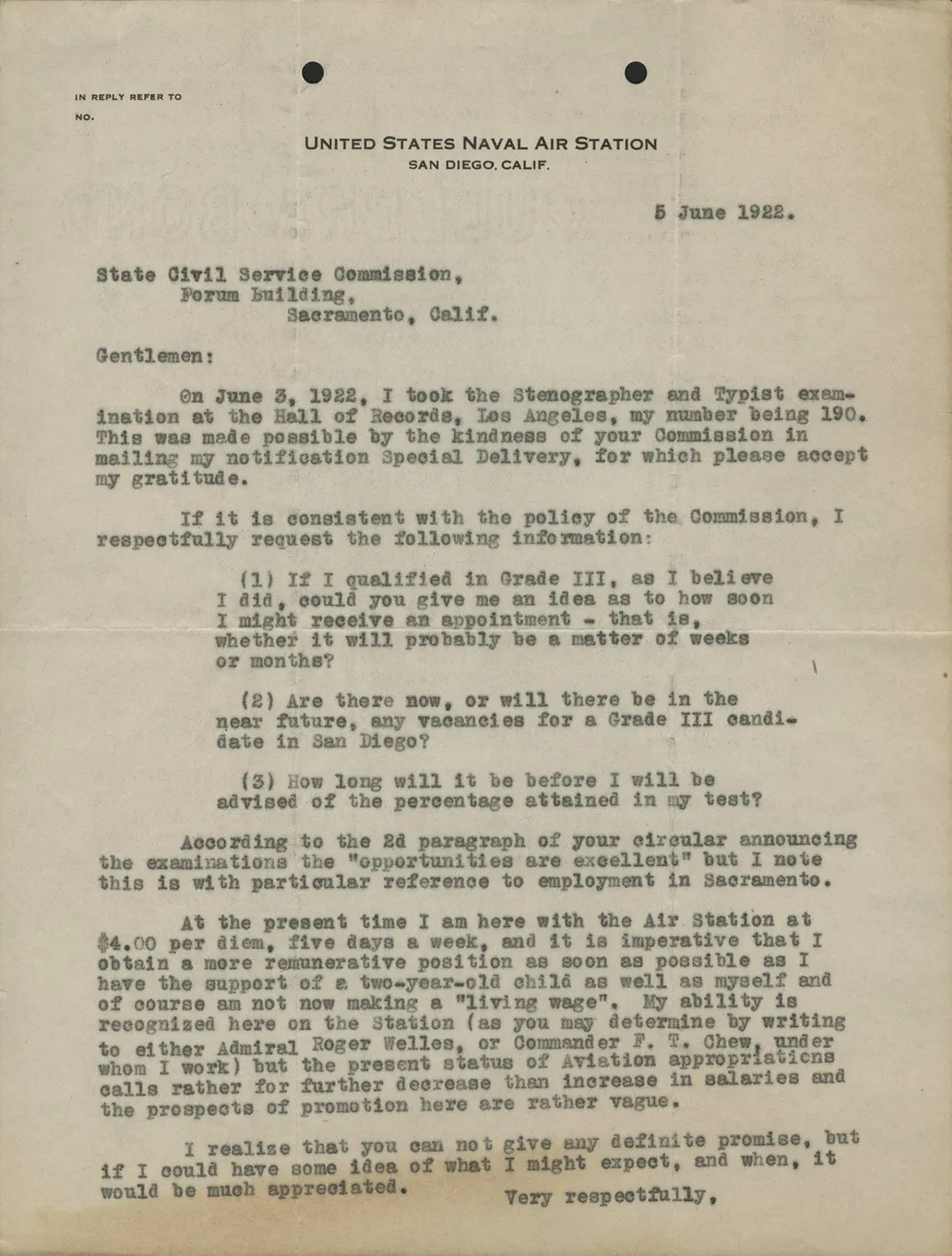

In June, 1922, two years after being honorably discharged from the Navy, single mother Ruth Creveling was struggling to make ends meet.

“It is imperative that I receive a more remunerative position as soon as possible,” Creveling wrote emphatically to her employer, California’s State Civil Service Commission, “as I have the support of a two-year-old child as well as myself and of course am not now making a ‘living wage.’”

Creveling’s bold letter is now displayed as part of the exhibition “In Her Words” at Smithsonian’s National Postal Museum. Her request for a living wage rings familiar–echoing today’s minimum wage debates–but its writer carries the prestige of being one of the first women to enlist in the U.S. military.

“You don’t think that this is going on one hundred years ago,” says museum curator Lynn Heidelbaugh, of the surprisingly relatable difficulties and achievements of Creveling and the other women of World War I. “But they are modern women.”

American pop culture has long championed women’s contributions during World War II. The American imagination readily conjures up factories full of “Rosie the Riveters,” with their sleeves rolled up and their hair tamed by patriotic red bandanas. While men fought abroad, women resolutely performed the necessary home front tasks to support the effort. But decades earlier women made essential contributions during the first World War—in factories, certainly, but also as nurses, volunteers for aid groups abroad, and, like Creveling, as the first enlisted women in the United States military.

Creveling was a yeoman (F), a gender distinction used to ensure that women weren’t assigned tasks or locations permitted only to men. While the enlistment itself defied gender roles, the tasks of a yeoman didn’t typically challenge them—the position was primarily a clerical job, and while yeomen (F) occasionally fulfilled the duties of a mechanic or cryptographer, women more often performed administrative tasks.

“Their duties are still very much along feminine lines,” Heidelbaugh says. But they did work alongside men, and surprisingly, they received the same wages, if they were able to rise to the same rank (despite facing greater restrictions)–more than 40 years before the Equal Pay Act of 1963.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/50/4050bf3a-3485-419e-8ded-820b422aa70d/5508_p_027.jpg)

What led to the seemingly radical change that, suddenly and at the height of the war, allowed women to join the U.S. military ranks and make the same salary as men?

Well. . . It was an accident.

Vague language in the Naval Act of 1916 about who should be allowed to enlist in the U.S. Navy reserve force–"all persons who may be capable of performing special useful service for coastal defense”–created a loophole that suddenly opened doors to women.

The act’s lack of clarity ended up being something of a godsend for the Navy, which was eager to recruit women for office tasks to make more men available for the front lines. But women who gained valuable work experience and a rare opportunity at equal pay clearly were the winners.

The assertive tone of Creveling’s letter speaks to her newfound determination to fight for the wages and opportunities she now knew from experience she had earned. That minor ambiguity in the Naval Act of 1916 become a watershed in the history of women’s rights—it was proof and evidence of a woman’s workplace commitment and flew in the face of critiques of the time that women were weak and unable to perform the same duties as men.

The 11,000 Navy “yeomanettes” that eventually enlisted during the war became trusted compatriots. Yeomen (F) worked with classified reports of ship movement in the Atlantic, translated and delivered messages to President Woodrow Wilson, and performed the solemn task of assembling the belongings of fallen men for return to their families. And they were recognized for their efforts: “I do not know how the great increase of work could have been carried out without them,” remarked Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels in his 1922 book Our Navy at War. Their competence and impact was undeniable to their male peers, and their service helped pave the way for the 1920 passing of the 19th amendment giving white women the right to vote.

That’s the point of the Postal Museum’s show, says Heidelbaugh: crafting individual narratives using ordinary personal mementos, especially letters, and using those narratives to illustrate the larger historical point. “We want to do history from the individuals’ perspectives,” Heidelbaugh says, “from the bottom up.”

Although female nurses could not enlist until 1944, they had long been vital contributors to U.S. war efforts. Nurses served in the military beginning with the Revolutionary War, and both the Army and Navy Nurse Corps–exclusively white and female–were established in the early 1900s. Black women were formally excluded from military nursing positions until 1947.

Military nurses, who were typically nursing school graduates, were not afforded the wages or benefits of enlisted soldiers and yeomen (F), despite often believing that enlistment was what they were signing up for, according to Heidelbaugh.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/45/52/4552ef01-0bc5-4de6-b5bc-5cf8da744db3/wwianc_699-001_edtd.jpg)

Pay inequity and lack of rank presented difficulties on the job, too: nurses struggled with how to interact with superior officers and orderlies; confusion reigned because women with deep medical expertise and knowledge lacked status and authority in the military hierarchy.

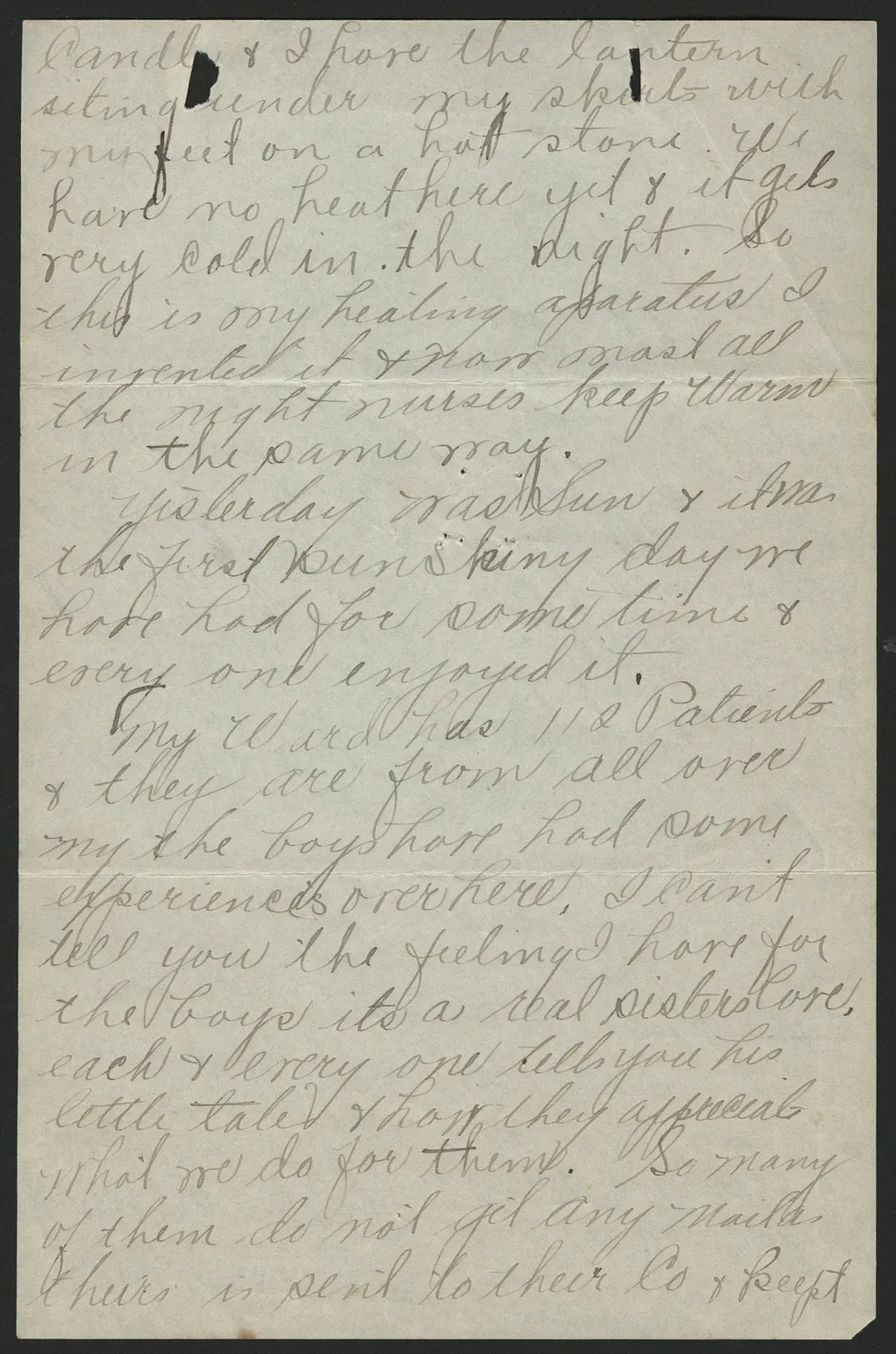

In 1918, Army nurse Greta Wolf describes disobeying orders in a letter to her sister and brother-in-law, a gutsy move given that military censorship of letters meant that a superior was likely to see her message. She had been told not to speak with the ill and injured enlisted men she treated. Her response was hardly insubordination, but rather her professional obligation to give comfort and succor to her patients: “I can’t tell you the feelings I have for the boys,” Wolf writes. “It’s a real sister’s love. Each and every one of them tells you his little tale and how they appreciate what we do for them.”

Heidelbaugh concedes that while the letters in the exhibition offer an intimate understanding of the lives of these historic women, we often unintentionally bring our “modern sensibilities” to their century-old stories. But from the personal journals of another World War I army nurse who optimistically collects the contact information of coworkers so they can keep in touch when they return to the states, to the letter where a YMCA volunteer tells her mother how proud she would be of the doughnuts she managed to make for the soldiers despite having no eggs or milk, it’s difficult to see the women of World War I as anything but the very model of modernity.

“A lot of the letters end with ‘I’ll tell you more when I get home,’” Heidelbaugh says.

We can only imagine what tales they had to tell.

"In Her Words: Women's Duty and Service in World War I," developed in partnership with the Women In Military Service for America Memorial Foundation, is on view at the National Postal Museum in Washington, D.C. through May 8, 2018.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/2018-01-17_07.39.24_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/2018-01-17_07.39.24_2.jpg)