How the Heated, Divisive Election of 1800 Was the First Real Test of American Democracy

A banner from the Smithsonian collections lays out the stakes of Jefferson vs. Adams

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/da/ea/daea3814-a92b-4d5b-83b2-0bfc1383a56e/oct2016_a01_nationaltreasurejeffersonbanner.jpg)

On a windy afternoon in February 1959, 14-year-old Craig Wade scooped up what seemed to be a crumpled rag that was blowing, tumbleweed style, across a railroad track in his hometown, Pittsfield, Massachusetts. He later told a local newspaper that he simply “likes to save things.”

Wade had scavenged a one-of-a-kind relic of American political history, identified only when a younger brother, Richard, took the find to his fifth-grade teacher. The victory banner—featuring a crudely drawn cartoon of Thomas Jefferson and an American eagle, inscribed with the motto “T. Jefferson President of the United States of America/John Adams is no more”—turns out to be a precious souvenir from the pivotal 1800 American presidential contest. Designed by an anonymous Jefferson supporter, this piece of political folk art symbolizes a defining test of our fledgling democracy: the ceding of power from one political party to another.

It also speaks loudly to us today because the election demonstrates that partisan rancor was a fact of our national political life from the outset. The founding generation cautioned against the divisiveness of “factions.” But in the absence of fully developed parties, the election of 1800 quickly devolved into a cutthroat contest. The main factions were organized around personalities—John Adams, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr. No small egos here: The stage was set for wide-open war.

Adams had entered the presidency in 1797 professing his “positive passion for the public good.” Yet Adams, who demanded deference to hierarchy and class, was contemptuous of new forms of political democracy. He viewed with alarm Jefferson’s affection for the early ideals of the French Revolution, seeing Jefferson and the growing Democratic-Republican societies around him as a Jacobin menace.

When the French Navy seized American ships carrying British goods, the so-called Quasi-War, which was undeclared, broke out in 1798. Adams became wildly popular. He sponsored the Alien and Sedition Acts, which allowed the president to deport immigrants suspected of disloyalty and to prosecute dissenting political opinion. Adams appeared in public in full military uniform, wearing a sword.

Hamilton, who had been Washington’s confidential aide and secretary of the Treasury, tried to use the crisis to vault himself to supreme power. As inspector general of the Army, Hamilton became the virtual commander in chief and regent of the administration. An immigrant himself, he now moved to deport nearly all immigrants.

Jefferson—who observed that he and Hamilton “were daily pitted in the cabinet like two cocks”—advised his followers that Federalist exploitation of war fever would soon enough prove its undoing. “A little patience,” he wrote, “and we shall see the reign of witches pass over, their spells dissolve, and the people, recovering their true sight, restore their government to its true principles.”

The presidential race between Adams and Jefferson turned on the outcome in New York, controlled by Aaron Burr’s political machine. After the Jeffersonians swept the legislative elections on May 1, 1800, Jefferson took Burr as his running mate. Hamilton—who despised Burr and called him an “embryo Caesar”—urged New York Gov. John Jay to permit the state legislature to choose presidential electors to prevent Jefferson—“an atheist in religion and a fanatic in politics”—from becoming president. Jay refused.

Adams now saw Hamilton’s power grab in his administration and purged his cabinet of Hamilton’s men. Hamilton, today lionized in Ron Chernow’s biography—not to mention on Broadway—was skewered by Adams as “the greatest intrigue[r] in the World—a man devoid of every moral principle—a Bastard....”

Hamilton responded by launching a campaign to destroy Adams, describing a president possessed by “vanity without bounds, and a jealousy capable of discoloring every object... a man destitute of every moral principle.”

Ultimately, the party of Jefferson and Burr—the Democratic-Republicans—prevailed in the election. But the arcane complexities of the Electoral College process at the time resulted in an equal numbers of votes for Jefferson and Burr. Hamilton’s suspicion of Burr overrode his fear of Jefferson. One of Hamilton’s allies cast the ballot that broke the tie and gave the election to Jefferson.

Eventually, Adams and Jefferson would reconcile. As for that bitterly contested election, Jefferson would later write that “The revolution of 1800...was as real a revolution in the principles of our government as that of ’76 was in its form.”

Related Reads

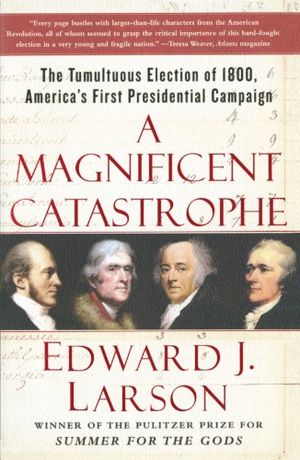

A Magnificent Catastrophe: The Tumultuous Election of 1800