The Electric Organ That Gave James Brown His Unstoppable Energy

What was it about the Hammond organ that made the ‘Godfather of Soul’ say please, please, please?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/40/47/40475fc5-3689-4564-9d2b-d7637f93f57b/apr2018_a01_prologue.jpg)

James Brown always knew his measure. He thought very highly of his favorite person, James Brown, and was convinced that guy could do just about anything he set his mind to.

Asked how he survived his earliest years, when he was penniless and raised in a brothel, Brown explained, “I made it because I believed I’d make it.” When asked why he still performed into retirement age, he explained to the interviewer, “I don’t do it for the show. I do it for the feeling of humanity.” Humanity needed the Hardest Working Man in Show Business.

Everything about him was big, everything came in multiples: Brown boasted of the Lear jets and furs and radio stations he owned, how in a year he would perform more than 600 hours onstage, play more than 960 songs on at least eight instruments.

And yet, there was one thing that Brown didn’t boast about: playing the Hammond B-3 organ. He loved that thing, maybe because he never could quite own it. Brown traveled on the road with the instrument (today residing in the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture), composed music with it and smiled at the buzz it generated. It sounded raw and tender, damaged and from the heart—a sound embodied in the title he gave to a 1964 album featuring his organ playing: Grits & Soul. He bragged about what he could do on the stage, but he remained revealingly modest about what he was able to achieve on the keys.

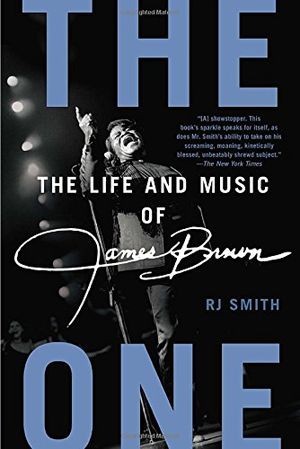

The One: The Life and Music of James Brown

The definitive biography of James Brown, the Godfather of Soul, with fascinating findings on his life as a Civil Rights activist, an entrepreneur, and the most innovative musician of our time.

To a jazz writer he confessed that he was not an organ player, “that’s for sure.” What he tried to do was play from his spirit, he explained, because “that’s about all I can do.” He went for feel, not mastery. “But that’s the way I express me.”

Around the time that Brown was born in the humid backwoods of South Carolina in 1933, an inventor in Evanston, Illinois, named Laurens Hammond was trying to create new sounds of his own. Hammond had already devised the first, now familiar, red and green 3-D glasses for an early experiment in techno-enhanced movies. He followed that up with a bridge table that shuffled four decks of cards at a time. In the early 1930s he was tearing up pianos, pondering how to get the big boom of a church organ while also making the instrument smaller and more affordable. The answer was to replace its reeds and pipes with an electric current.

James Brown couldn’t read music, and neither could Hammond. Both worked by feel, and belief, and both clearly got intense when they sensed they were onto something. Hammond debuted his first electric organ in 1935, and within three years he had sold more than 1,750 units to churches across America. It was perfect for African-American worshipers who were following the Great Migration up from the South, praying in enclaves without the means for a pipe organ.

The Hammond electrified faith, and it electrified the faithful, too, because it had a way of projecting its fervor out onto the streets of America. People took the crazy feelings the Hammond unlocked and blasted them past the church into the rec room, the jazz club, the honky-tonk. A whole bunch of new feelings, mixing sacred spaces and public places.

Note the words on Brown’s instrument: “God-father.” As the announcer at the Howard and the Regal and the Apollo and theaters everywhere else put it, Brown was, of course, “the Godfather of Soul.” But the wording on the black leather that handsomely wraps the instrument frames it a little differently, and meaningfully. This instrument separates, and balances, the god and the father, the sacred and the human. If God was in everyone, and if the Hammond was available to everyone, well, mastering it was...still not easy. The Hammond permitted multiple pedals that multiplied your options, but Brown liked just one. He stayed on the One.

He worshiped the early generations of jazz players who took the organ out of the church and into the chitlins spots and the smoky nightclubs, masters like Jimmy Smith, Jimmy McGriff and Jack McDuff. He knew he wasn’t them. The crowd made James Brown feel holy; the organ humbled him. It made him feel human. Maybe that’s why he kept it close, like a secret.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.