When Robert Kennedy Delivered the News of Martin Luther King’s Assassination

Months before his own slaying, Kennedy recalled the loss of JFK as he consoled a crowd of shocked African-Americans in Indianapolis

:focal(1668x2530:1669x2531)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f6/b1/f6b1e0a2-98d7-4c35-a070-e1154d8b2c6e/npg_78_tc503_kennedy_2r.jpg)

Martin Luther King Jr.—murdered.

The news of April 4, 1968, was like a body blow to Senator Robert Kennedy. He “seemed to shrink back,” said John J. Lindsay, a Newsweek reporter traveling with the Democratic presidential candidate. For Kennedy, King’s slaying served as an intersection between past and future. It kindled memories of one of the worst days of his life, November 22, 1963, when J. Edgar Hoover coldly told him that his brother, President John F. Kennedy, had been shot and killed in Dallas. Furthermore, it shook Kennedy’s belief in what lay ahead. He sometimes received death threats and lived in anticipation of gunshots.

Half a century ago, when his campaign plane reached Indianapolis on that night, Kennedy learned of King’s death. The civil rights leader had been gunned down in Memphis, where he led a sanitation workers’ strike. Kennedy had planned to appear in a black Indianapolis neighborhood, an area the city’s mayor considered too dangerous for a rally. City police refused to escort Kennedy. Nevertheless, he proceeded as a messenger of peace in a time soon to become hot with rage. Reaching the neighborhood, Kennedy realized the boisterous crowd was unaware of King’s death.

Climbing onto a flatbed truck and wearing his slain brother’s overcoat, Kennedy looked at the crowd. Through the cold, smoky air, he saw faces upturned optimistically and knew they soon would be frozen in horror.

At first, he struggled to gain his rhetorical feet. Then, one of the most eloquent extemporaneous speeches of the 20th century tumbled from his lips. During the heartfelt speech, Kennedy shared feelings about his brother’s assassination—something he had avoided expressing, even to his staff. The pain was too great.

Clutching scribbled notes made in his car, RFK began simply: “I have bad news for you, for all of our fellow citizens, and people who love peace all over the world, and that is that Martin Luther King was shot and killed tonight.” Gasps and shrieks met his words. “Martin Luther King dedicated his life to love and justice for his fellow human beings, and he died because of that effort. In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in.”

Kennedy knew King’s death would generate bitterness and calls for vengeance: “For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and distrust at the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling,” he said. “I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man. But we have to make an effort in the United States, we have to make an effort to understand, to go beyond these rather difficult times.”

After the initial shock, the audience listened silently except for two moments when they cheered RFK’s peace-loving message.

“It’s a very un-speech speech,” says Harry Rubenstein, a curator in the division of political history at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. “When you watch Kennedy giving the news of King’s assassination you see him carefully and hesitantly stringing his ideas together. Ultimately, what makes the speech so powerful is his ability to share the loss of his own brother to an assassin, as he pleas with his audience not to turn to violence and hate.” Rubenstein concludes.

“It’s the first time he talks publicly about his brother’s death and that he has suffered the angst and anguish of losing someone so important to him, and they were all suffering together . . . . everyone on the stage as well as in the crowd. And there was a real vulnerability in that,” adds curator Aaron Bryant from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

“It was such a risky thing for him to do as well because he was confronting a crowd that was ready to retaliate for the death of Martin Luther King, but he was ready to confront any retaliation or anger that people might have felt over King’s death. That took a certain amount of courage and spiritual power and groundedness,” says Bryant.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/78/58/7858f5e2-c4f4-4ae1-896f-4a56f86cd3ad/nmah-jn2017-00130-000001.jpg)

When Kennedy reached his hotel, he called King’s widow Coretta Scott King in Atlanta. She said she needed a plane to carry her husband’s body from Memphis to Atlanta, and he immediately promised to provide her one.

As the night proceeded, a restive Kennedy visited several campaign staffers. When he talked to speechwriters Adam Walinsky and Jeff Greenfield, he made a rare reference to Lee Harvey Oswald, saying JFK’s assassin had unleashed a flood of violence. He reportedly told “Kennedy for California” organizer Joan Braden, “it could have been me.”

The next day, he prepared for an appearance in Cleveland, while his staff worried about his safety. When a possible gunman was reported atop a nearby building, an aide closed the blinds, but Kennedy ordered them opened. “If they’re going to shoot, they’ll shoot,” he said. Speaking in Cleveland, he asked, “What has violence ever accomplished? What has it ever created? No martyr’s cause has ever been stilled by his assassin’s bullet.”

Meanwhile, African-American anger erupted in rioting across more than 100 American cities, with deaths totaling 39 and injuries 2,500. After the senator finished his campaign swing, he returned to Washington. From the air, he could see smoke hovering over city neighborhoods. Ignoring his staff’s pleas, he visited riot-ravaged streets. At home, he watched riot footage on TV alongside his 8-year-old daughter, Kerry, and told her that he understood African-American frustration, but the rioters were “bad.”

Both Kennedy and his pregnant wife Ethel attended King’s Atlanta funeral, where they saw the slain leader lay in an open casket. They met privately with his widow. Mrs. King and Ethel Kennedy hugged upon meeting—by the end of the year both would be widows. Perhaps they recognized their shared burden of sorrow, even with RFK still standing among them.

On May 7, Kennedy won the Indiana primary. Three weeks later, he lost Oregon to U.S. Senator Eugene McCarthy of Minnesota, and on June 4, he triumphed again in California and South Dakota. After RFK’s early-morning victory speech in Los Angeles, Sirhan Sirhan, a Palestinian Jordanian who opposed Kennedy’s support for Israel, shot the senator in the head. He lay mortally wounded on an Ambassador Hotel pantry floor while TV cameras rolled. His face wore an expression of resignation. Robert Kennedy died a day later.

His funeral ceremonies began with a Mass in New York’s Saint Patrick’s Cathedral, and his coffin was carried from New York to Washington on a slow-moving train. Mixed gatherings of citizens lined the railroad awaiting an opportunity to demonstrate their sense of loss and to own a piece of history. Members of the Kennedy family took turns standing on the back of the last car, which carried the coffin in full view of the public. When the train reached Washington, an automobile procession passed Resurrection City, an encampment of 3,000-5,000 protesters, on the way to Arlington National Cemetery.

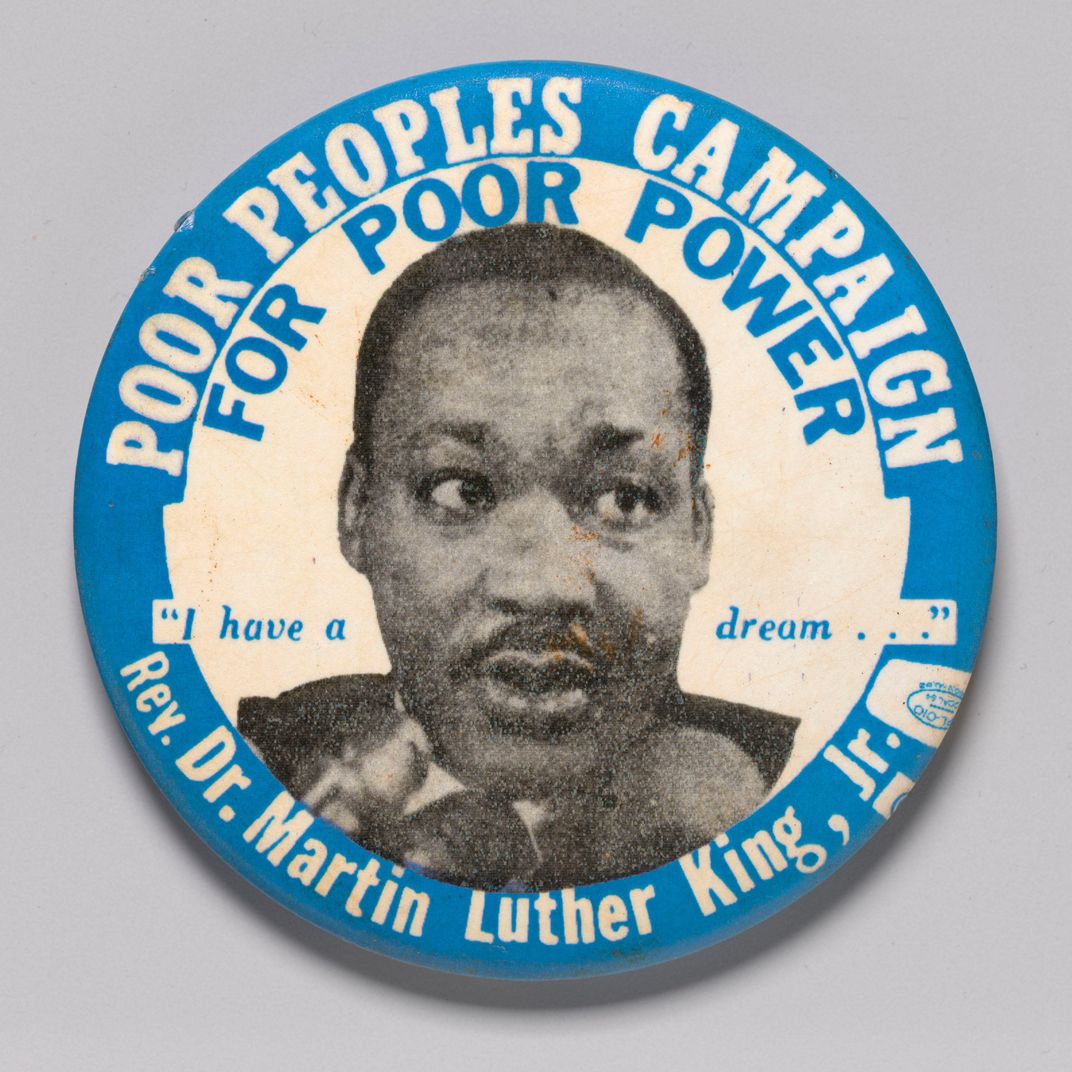

Organized by the Poor People’s Campaign, the shantytown on the National Mall included poor Southerners who traveled from Mississippi in covered wagons. King had planned to lead the demonstration and hoped to build a coalition supporting the poor of all colors. His organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, developed an Economic and Social Bill of Rights and sought $30 billion in spending to end poverty. Loss of a charismatic leader like King created both emotional and organizational obstacles for the SCLC, says Bryant, who has organized a Smithsonian exhibition, entitled “City of Hope: Resurrection City and the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign.”

Though in mourning, the SCLC went ahead with the demonstration because they “wanted to honor what would be King’s final and most ambitious dream,” according to Bryant. King was changing his movement through the Poor People’s Campaign, making a transition from civil rights to human rights. Economic rights were taking center stage. Bryant says that King believed “we should all have access to the American dream.”

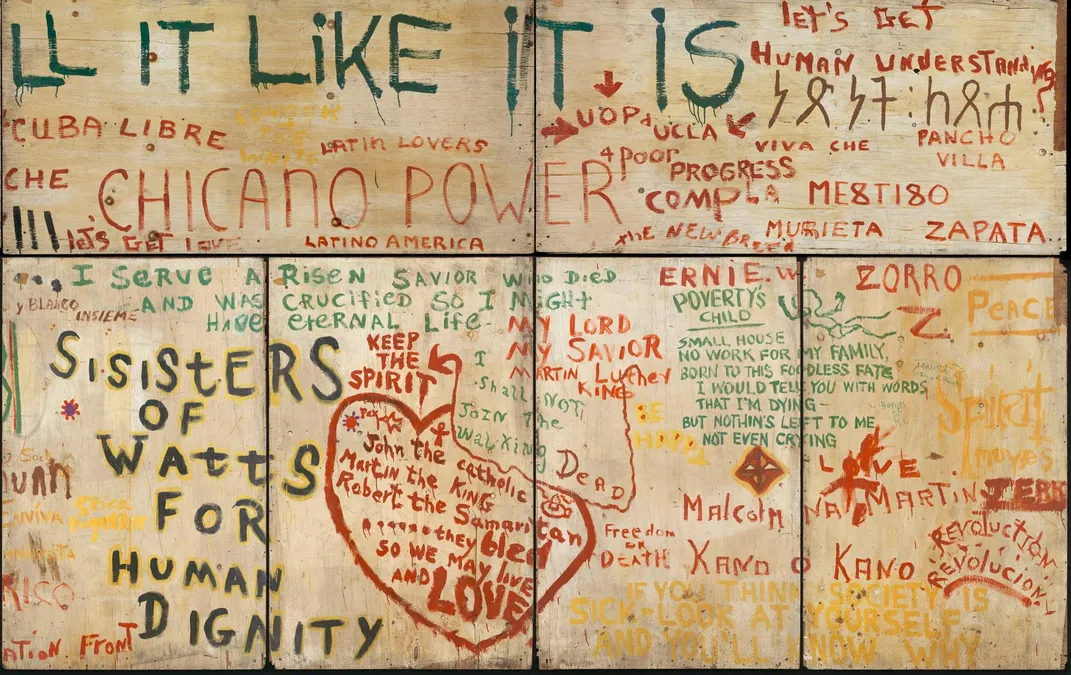

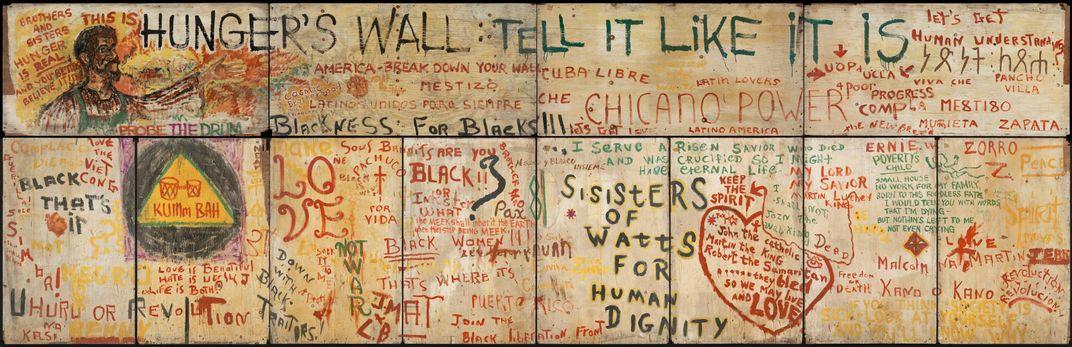

As Kennedy’s funeral procession passed, “people were really moved, of course, because he was a very important part of how the campaign happened,” explains Bryant. Some raised their fists in a “black power” salute; others sang the Battle Hymn of the Republic. Among the remains of Resurrection City after its temporary permit expired June 20 was a piece of plywood with a simple message of loss and hope:

John the Catholic

Martin the King

Robert the Samaritan

They bled so we may live and LOVE.

This piece of wood was one of 12 panels in the Hunger Wall, a mural rescued from Resurrection City. Two panels are on display in the Poor People’s Campaign exhibition, which is currently on view at the National Museum of American History. The show also includes a clip of Kennedy’s speech. Four more of the mural panels are on display at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

After a two-month manhunt, James Earl Ray, a white man, was arrested in London for King’s slaying. He confessed and although he later recanted, he served a life sentence until his death in 1998. Sirhan, now 73, remains in a California prison.

The “City of Hope: Resurrection City & the 1968 Poor People’s Campaign,” organized by the National Museum of African American History and Culture, is on view at the National Museum of American History.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alice_George_final_web_thumbnail.png)