The Story of Muckraker Upton Sinclair’s Dramatic Campaign for Governor of California

Sinclair was as famous in his day as any movie-star candidate who came later

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/2a/462a0ad5-7ee6-4327-acb4-e5282471a8b8/screen_shot_2017-09-18_at_95410_am.png)

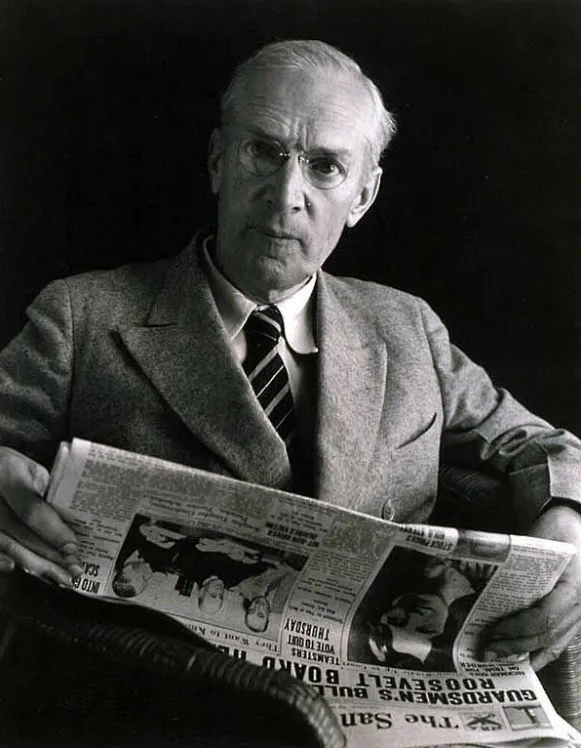

Upton Sinclair, born on this day in 1878, could have been California’s first star governor.

Sinclair was one of early twentieth century America’s biggest figures. The muckraking journalist and novelist made it his mission to expose unfair labor practices and discriminatory politics, earning him both fame and notoriety. Books like Oil!, which was adapted into the 2000s film There Will Be Blood, showed his crusading politics. And books like The Jungle, a fictionalized account of the meatpacking industry, exposed unsanitary practices and health violations and led to food safety reforms.

Like many journalists before and since, Sinclair finally found it hard to simply document injustice, and instead tried to fight it by becoming a politician. But, as in his journalistic career, his approach was unconventional. Sinclair’s 1933-34 run for Governor of California was as history-making as any of his books.

A newsmaking campaign launch

Sinclair’s campaign began in September 1933, when he registered to vote as a Democrat, according to the University of Washington’s Mapping American Social Movements Through the 20th Century blog. Sinclair “had just celebrated his birthday,” the blog writes. “Fifty-five years old, he was one of America’s best-known writers.” A few days later, he said he was running for the Democratic nomination for governor.

“One of the most dramatic and influential contests in California history, it helped change the political landscape of the nation,” writes Mapping America. But it wasn’t Sinclair’s first run for office. Sinclair had run as California's “Socialist candidate for the U.S. Senate in 1922 and as their gubernatorial candidate in 1926 and 1930,” writes historian Donald L. Singer. Even though his political goals were more aligned with the Socialists than mainstream Democrats, Sinclair switched parties because he recognized that he was more likely to win as a Democrat, Singer writes.

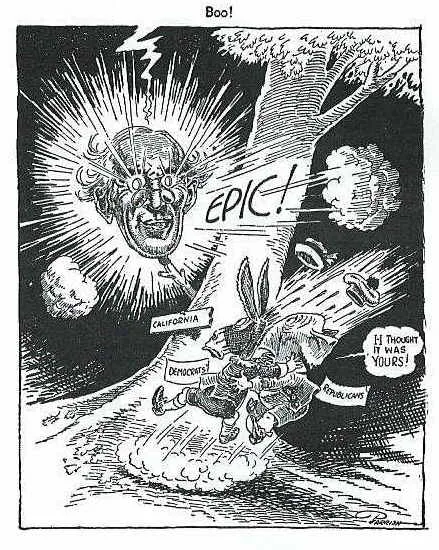

An EPIC platform

Sinclair’s platform was known as EPIC: End Poverty in California. (This was decades before “epic” came to have the popular meaning of “impressive.”) Sinclair articulated his plan by using his authorial skills to produce a book titled I, Governor of California and How I Ended Poverty: A True Story of the Future. This unconventional narrative contained a description of “his nomination, his victory and his triumphant execution of the EPIC program,” Singer writes. His plan featured sweeping changes, including abolishing the sales tax, a near-universal pension plan and a number of public bodies that would oversee everything from appropriating idle land to creating factories where the unemployed could work.

EPIC was a hit. Hundreds of EPIC clubs, aimed at spreading the word about the proposed reforms and getting Sinclair elected, sprang up around the state–more than 800 by the time of the primaries.

An EPIC newspaper

Sinclair also started running EPIC News, a tabloid spreading his messages. “In addition to campaign news, the paper attracted readers with sensationalistic exposés and attractive political cartoons,” Mapping America writes. “In late May [1934] the newspaper became a weekly and a San Francisco edition was added as the campaign caught fire and circulation soared.” EPIC News, which was edited by another journalist, regularly featured several pieces bearing Sinclair’s own byline.

On August 29, 1934, the newspaper ran a special victory issue marking Sinclair being chosen as Democratic nominee for the California governorship. “Personally, I am not the elbowing sort of person, and only in a time of desperate crisis would I have thought of acting as I have,” Sinclair wrote in an editorial.

All seemed poised for success. His politics may not have been too socialist for Californians, but they were too socialist for businesses that had a stake in California, writes Gilbert King for Smithsonian Magazine. “Business interests across the country suddenly began pouring million dollars into a concerted effort to defeat him,” King writes. “The newspapers pounced, too, with an unending barrage of negative coverage.” The first-ever attack ads also appeared in movie theater newsreels. By the time of the election, “millions of viewers simply did not know what to believe anymore,” King writes. Sinclair lost, but the legacy of his campaign and the smear campaign launched against him echoes in politics today.