Samantha Mewis, a 6-foot-tall midfielder known for her aggressive dribbling and passing on the pitch, had already played on teams that had won the professional National Women’s Soccer League championships three times. By the time she and a group of female colleagues sued the U.S. Soccer Federation, Mewis had brought home the 2019 World Cup title and secured four Olympic gold medals. The women were seeking equal pay with male players, many of whom lacked the type of dominance or star power that Mewis and her compatriots had demonstrated.

The national team wasn’t governed by the historic civil rights law Title IX that turns 50 this month, but the statute’s very existence makes it possible for those women to be playing soccer at an international and professional level. Before the law was enacted in 1972, elite athletics were more or less out of reach for women.

The female soccer stars who sued were initially rebuffed when a judge dismissed their claims in 2020. But, suddenly, in February 2022, U.S. Soccer agreed to pay the women some $24 million in back pay. It was a tacit admission that pay inequality was indeed an issue. In May, U.S. Soccer announced that going forward, male and female players on the national teams would receive equal pay and bonuses, including for the FIFA World Cup.

On the 50th anniversary of Title IX’s passage—June 23—the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History opens the new exhibit, "We Belong Here," displaying a U.S. National team jersey that Mewis wore for the team's 2019 World Cup win. The exhibit also includes a tennis racquet used by Naomi Osaka to win the U.S. Open in 2020 and a T-shirt worn by transgender, non-binary skateboarder Leo Baker.

Each of those athletes has a story that would not have been possible without Title IX.

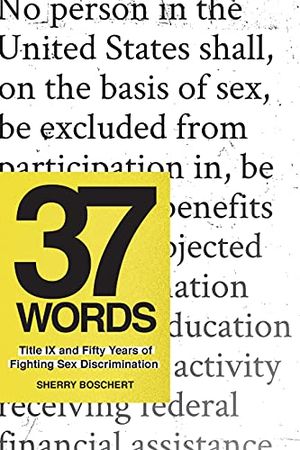

The 1972 legislation declared in its first 37 words that “No person in the United States shall, on the basis of sex, be excluded from participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any educational program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/11/38/1138070f-ebc0-4a57-b72b-187afd4e87d5/gettyimages-1240863607.jpg)

The fight for Title IX got its start when Bernice “Bunny” Sandler was denied the opportunity in 1969 to become a professor at the University of Maryland, despite impeccable credentials. She was told by a male faculty member that she “came on too strong for a woman.” Once she and co-movement leaders like Margaret Dunkle got the ball rolling, they were focused on education and employment opportunities, not sports.

“They had no clue really, that it was going to be this big deal in sports,” says Sherry Boschert, a journalist and author of 37 Words: Title IX and Fifty Years of Fighting Sex Discrimination. “The topic of sports came up exactly three times in all of the discussions leading up to Title IX’s passage,” she says.

Susan K. Cahn, a sports, gender and LGBTQ historian at University at Buffalo College of Arts and Science, agrees. “No one thought about sports when the law was passed,” says Cahn. But when women began using the statute to seek equality in sports, “it was really a shock to the male sports world,” she says. Title IX has “partly been associated with sports because that’s where some of the most dramatic change occurred, and that’s where the battles occurred,” Cahn says.

Many Americans of a certain generation—especially those who were teenagers when the law passed—equate Title IX with the opportunities it gave them to compete.

Girls and women were long shut out of competitive scholastic sports; in part, because female physical education instructors believed that participation was more important than competition, and there was some concern that women would become masculinized, says Cahn.

In the 1960s, a younger generation of PE teachers pushed for more competition and even intercollegiate competition. And some national sports organizations—in swimming, golf and some water sports, for instance—also devoted more resources to coaching and improving performance for female Olympians, largely because the Americans kept getting beaten so resoundingly by Soviet women, says Cahn.

Boschert notes that there were no organized sports for girls when she was in high school in the early 1970s. But by the time she got to college at Amherst in 1976, an enterprising woman—who became the school’s first female coach—recruited Boschert to play on what became Amherst’s first girls’ basketball team.

Today, women make up 44 percent of all National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) athletes, compared to 15 percent before Title IX, when there were fewer than 30,000 female collegiate players, according to the Women’s Sports Foundation.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7b/ea/7beae658-8755-4eb9-b186-346f3fcddc03/jn2022-00337.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e9/7d/e97d9612-c3f1-4318-95a4-4c821a3064e9/untitled-1.jpg)

The report estimates that high school girls have an additional three million opportunities to play now, as compared to before Title IX. Still, there is an imbalance. Three-quarters of boys participate in high school sports, compared to 60 percent of girls. Women make up two-thirds of college enrollment, and yet they have just 43 percent of the college sports opportunities, says the Foundation.

The fight for equality has extended beyond just female—and mostly white—athletes to female athletes of color and transgender and non-binary competitors.

At the Smithsonian exhibition, Osaka represents an intersection of Title IX-related issues. As a biracial woman, she had a rockier path to the top of the tennis pyramid than many white competitors. In 2020, Osaka threw her support behind the racial justice movement, wearing masks with the names of Black individuals who had been victims of police violence. A half-year later, she withdrew from the French Open after she was fined for skipping a press conference. Osaka soon spoke out about her struggles with anxiety and depression and became a leading advocate for better mental health support for athletes.

37 Words: Title IX and Fifty Years of Fighting Sex Discrimination

A sweeping history of the federal legislation that prohibits sex discrimination in education, published on the 50th anniversary of Title IX

Title IX, because it funds programs for students and student-athletes, is supposed to help address some of these issues, notes Smithsonian curator Jane Rogers, who organized the show.

Rogers chose to include Baker, the skateboarder, in part to prompt the question of “what happens in sports if gender isn’t an issue,” she says. On exhibit is a white T-shirt with “they/them” in black lettering on the front. Baker wore the shirt as declaration in a 2019 video with Miley Cyrus. It was the first time they had come out as non-binary.

Before transitioning, Baker was selected to the first-ever U.S. Women’s National Skateboarding Team and was set to go to the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. But Baker decided to resign from the team rather than compete as a woman. Formerly known as Lacey, they changed their name to Leo at the same time.

Baker's story, say Rogers, is “meant to be thought-provoking and generate discussions among the visitors.”

That’s especially true as the international swimming federation, FINA, announced on June 19 that it would prohibit transgender women from competition unless they had initiated testosterone suppression treatments by the age of 12 and prior to puberty. In the U.S., a growing number of states are seeking to prohibit transgender athletes from participating in sports. At least 18 states have passed laws that ban transgender athletes in public schools from playing in a sport that is not consistent with their birth gender. Many of the laws bar participation in club sports as well as competitive sports.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/53/8f/538f1b8f-55d6-4e1a-92a7-a9b0efb2ae05/screen_shot_2022-06-16_at_115753_am.png)

The federal government has clarified that Title IX prohibits discrimination against transgender athletes. Cahn says it’s not clear whether the state laws barring participation are on solid legal ground.

To Boschert, the arguments against trans athletes echoes the line of attack that has been taken against lesbian and gay people, who endured insults, humiliation and other public acts of abuse. All of these same tactics are being employed against transgender individuals, she says. Proponents of the state laws “primarily are about exclusion,” she says.

However, Boschert adds, “there are a surprising number of women’s advocates who also do not want to see trans women in competitive sports because of this long history of women not getting their fair share.”

That’s also an argument against eliminating separately-gendered sports, says Cahn. Most feminists do not support that because it would ultimately reduce or eliminate the increased opportunities for women that were created by Title IX, she says. For instance, if there was just one basketball team at a college, few women would likely make the team, Cahn says.

Gender-separate teams may be eliminated in some sports like riflery or dressage, where height and strength and power and speed do not confer specific advantages, says Cahn.

While the fight over transgender athletes is the highest-profile Title IX-related battle, others continue to simmer. Male high school and collegiate teams frequently challenge the law on multiple fronts and violations that never make it to court occur with regularity, Cahn says.

While most people today would never think to bar their daughters from playing sports, “there’s still a belief that girls and women aren’t as interested as boys and men,” she says.

That belief has been leveraged by schools to cut funding for or not offer women’s sports. In addition, many schools eliminate a men’s sports program and then claim it was because the money was required to go to fund a women’s activity. Boschert says that following the intent of the law would mean it would be two separate pots of money—it would not pit men’s against women’s sports. Much of the cutbacks come because of the outsize nature of football and basketball programs, she says.

At most universities, operating budgets for male sports and male coaches’ salaries far outstrip those for women’s sports and coaches, and women also have fewer scholarship opportunities than men, notes Cahn. Even though there “really has been almost revolutionary change,” since the 1970s, “we don’t have gender equity yet,” she says.

Boschert says Title IX is not just a tool for gender equity, but for addressing many injustices. “All those gains in athletics, they primarily went to white women,” she says. “We need to deal with racial and ethnic discrimination, we need to deal with socioeconomic discrimination,” and think about disability-related issues also, says Boschert.

“If we don’t do that, Title IX will never fully be a success,” Boschert says.

“We Belong Here” opens June 23, 2022, on the 50th anniversary of the Title IX civil rights statue, at the National Museum of American History.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(1500x1000:1501x1001)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f7/0f/f70fbd46-05a5-4c98-9113-3dca447e48eb/gettyimages-1160702323.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)