Performer and entertainer Celia Light remembers watching the reality competition television show RuPaul’s Drag Race while still a senior in high school. She knew then what she was meant to be. But before Light even put on drag makeup and couture for the first time, she knew she needed a stage name.

“I wanted to name myself after someone I’m connected to, after someone I feel has had a really positive impact on my life,” Light says. That person was the Cuban American singer Celia Cruz, the “Queen of Salsa,” who died in 2003 after an award-winning career that transcended borders and connected with Spanish-speaking and non-Spanish-speaking audiences worldwide.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0e/c7/0ec7ae5a-1482-4093-92a7-fd65d65cf100/gettyimages-85355721horizontal.jpg)

Light, 23, based in Austin, Texas, says she was inspired by Cruz, having grown up listening to her salsa music played at family gatherings and blasted in her home whenever her mother did the house cleaning. Drag names also tend to be a play on words—the Korean side dish kimchi is the inspiration for the name of the famous drag queen Kim Chi—so once she realized Celia Light sounded like “cellulite,” she knew that adapting her childhood idol’s name was destiny.

Light is now part of a community of entertainers and impersonators from cities like Miami, Austin, Chicago and New Orleans reviving the Queen of Salsa’s eye-catching fashion and extravagant stage presence. The Cruz phenomenon “speaks to drag culture,” she says, of the performances she offers at events ranging from private parties to local bars and restaurants. “There is a level of wanting to take femininity to its highest point and wanting to express it loudly and beautifully, and wanting to put it all out there,” she says.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/5c/31/5c314a05-d15f-4c97-95d0-26f87cfe0016/pride-celia-solo-promohorizontal.jpg)

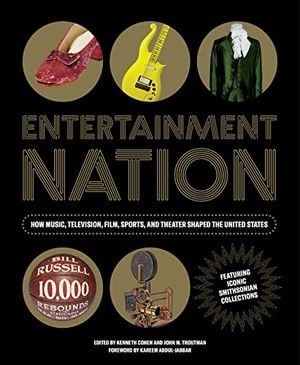

At the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, the Queen of Salsa’s legacy and iconic style are honored as part of the upcoming “Entertainment Nation,” an exhibition that explores how music, theater, television, film and sport have created large national conversations about social and political issues for more than 150 years.

Ashley Mayor, one of the organizers behind the exhibition—which has also been given the Spanish name “Nación del Espectáculo”—says Cruz rose to fame during a time when there was increased immigration from Latin America to the United States, and her story offers an important lens on today’s conversations about the Latino experience.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/e9/48/e948219c-fee6-44c1-a4bb-b85df8f2e01e/gettyimages-104810716.jpg)

“So many of her songs have withstood the test of time, both for the Latinx community as much as in global music,” Mayor says. “She is a phenomenon, so it made a lot of sense when we’re talking about music and its impact on society to include Celia in the show.”

Two of Cruz’s Cuban rumba dresses, known as bata cubana, and a pair of gold shoes are part of the museum’s collections. Cruz wore the orange bata cubana during performances at Carnegie Hall and the Apollo Theater. The gown is a combination of traditional and contemporary styles with undulating sleeves and a layered train. The other bata cubana is adorned with a Cuban flag design, featuring a shimmering star at the center and a mass of red, white and blue ruffles ornamenting the sleeves and skirt. Going on view in the exhibition are a custom-made pair of gold shoes. Crafted by Mexican designer Miguel Nieto using a clever design trick that seemingly defies gravity, the shoes have a high-heeled look without an actual heel.

“Drag queens that imitate Celia will wear that kind of performance apparel, and it’ll immediately signal to everyone to think of Celia,” says Mayor. “Her style really spoke a lot and made a huge impression, and inspired many folks to be more bold in their fashion choices.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/7b/5e/7b5efd9c-fbf0-4bbe-ab5a-4f1d02883bc0/celia-cruz-shoes.jpg)

Entertainment Nation: How Music, Television, Film, Sports, and Theater Shaped the United States

Entertainment Nation is a star-studded and richly illustrated book celebrating the best of 150 years of US pop culture. The book presents nearly 300 breathtaking Smithsonian objects from the first long-term exhibition on popular culture, and features contributors like Billie Jean King, Ali Wong, and Jill Lepore.

Many of Light’s wigs are colorful and dramatic like Cruz’s, including a long, flowing bright turquoise wig and another yellow one with bangs styled in an updo. “I feel that’s why what she does speaks to drag culture so much, especially a lot of Hispanic drag queens, because she wasn’t afraid to be loud and beautiful and colorful,” she says.

Light handmakes most of her drag costumes. “I take [Cruz’s] big colorful silhouette and I mold it to what I want to do,” she says.

An example is an all-white showgirl-inspired bodysuit adorned with arm gauntlets and ostrich feathers, and a gown inspired by the rainbow LGBTQ pride flag with ruffles at the hips and spiky shoulder pads.

Cruz’s songs, mostly popular hits like “La Vida Es un Carnaval” (“Life Is a Carnival”) and “La Negra Tiene Tumbao” (“The Black Woman’s Got Style”) are part of Light’s performances. “Yo Viviré,” the Spanish version of Gloria Gaynor’s famous record “I Will Survive,” always brings the house down, Light says, adding that even if audience members don’t themselves speak Spanish, they recognize the beat of the popular song and cheer and dance along.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/6c/55/6c5542c6-54e7-4f4a-b483-da42703ee049/gettyimages-2236631.jpg)

Cruz’s relationship with the American History Museum began in 1997, when she donated some of her personal items, Mayor says. Shortly after her death, the museum organized its seminal 2005 exhibition “¡Azúcar! The Life and Music of Celia Cruz,” named for her iconic catchphrase and featuring gowns, wigs and personal documents loaned from the Celia Cruz Foundation. In 2016, the foundation donated the items.

Hers was a fashion and style that resonated; audiences thrilled to her famous call—¡Azúcar!, or “sugar,” which originated, she always said, in a Miami restaurant when she told a server what she took with her coffee. Curator Stephen Velasquez, another of the exhibition’s organizers, says Cruz’s style allowed the performer to further connect with audiences, particularly when it came to the embellishments on her gowns. “When she’s dancing, [the ruffles] exaggerate the movements, and it makes you want to dance and makes you want to make the same movements,” he says.

“If I look into the audience and see somebody dressed better than me, I feel like I have failed,” Cruz confided in a 1998 interview with the museum. “People pay good money to come hear me sing, but also to see me sing, and I should always look the part.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/70/a2/70a2815d-2d0f-490f-9811-ab440b7ecaf8/cruz_dress.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/ef/9f/ef9f1435-ef5d-46d5-b2bd-73a088938154/cruzflagdress.jpg)

One of four children, Cruz was born Úrsula Hilaria Celia de la Caridad Cruz Alfonso de la Santísima Trinidad in Havana, Cuba, in 1925. Her singing career began in her teen years when her family members would take her to perform at cabarets. Before long, her performances on local radio stations had caught the attention of famous producers and musicians, and by 1950, she had become the first Black lead female singer of one of Cuba’s most popular orchestras, La Sonora Matancera.

But after the Cuban Revolution in1959, the orchestra’s vocal opposition to Fidel Castro’s socialist rule led to the group’s exile, and Castro barred them from ever returning to the island. Cruz would never set foot on Cuban territory again.

Cruz arrived in the U.S. in 1961 with former La Sonora band member Pedro Knight—who soon became her husband, musical director and manager. The couple settled in New Jersey and set out to launch Cruz’s solo career under Knight’s management, in performances celebrating Cuban heritage and the country’s music and traditions.

If I look into the audience and see somebody dressed better than me, I feel like I have failed.

Salsa music—a genre born from Latin dance music combined with Afro-Caribbean sounds—was gaining influence, and Cruz was quickly at the forefront. After joining Fania Records, a label devoted to salsa, in 1974, she collaborated with Johnny Pacheco, a Dominican musician and co-founder of the record label, and became the sole woman in the musical group the Fania All Stars.

With her operatic voice, she seamlessly navigated high and low pitches that defied her age while improvising rhythmic lyrics that added a unique flair. She focused on African elements of her identity during a time when the concept of Blackness wasn’t embraced by mainstream audiences.

In 1974, with artists B.B. King and James Brown, Cruz traveled to Africa as part of the live music festival “Zaire ’74,” where she gave a command performance. Her dress was a sequined, multicolored ruffled gown paired with dangly gold earrings that dropped to her shoulders.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c0/aa/c0aa8923-deee-46c2-a5d0-dc7df1a27048/gettyimages-74259091.jpg)

David Garcia, a music professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, regards the moment as one of the most iconic of her career, as well as an important moment for salsa music. “Given that the music, Cuban culture, so much of it owes its existence to West African and Central African cultures, I always see [the performance] as a return back to where this music, where our cultures, where our people came from,” he says.

Cruz’s music and fashion sense constantly evolved, and her style was timeless, Mayor says. She recorded 188 songs, received 23 gold records and won three Grammy Awards and four Latin Grammy Awards. She found community with multiple Latin American and American artists, collaborating with Gloria Estefan, Wyclef Jean, and Patti LaBelle, among others. She also starred in multiple films, was awarded a star on Hollywood Walk of Fame and was granted the American National Medal of Arts by President Bill Clinton in 1994. One of her last performances took place in the summer of 2002, in front of a large crowd at New York’s Central Park Summerstage, an outdoor performing arts festival. The following year, she died in her New Jersey home at the age of 77 from brain cancer.

“As she aged, she just became more bold and transformed in such a way that she started saying so much with her style,” says Mayor. “She has since become iconic, so much so that Celia imitators will point to iconic outfits from her career.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/38/2f/382f2a76-fb17-484b-875e-95c3951c4484/purple_sparle_solo_celia.jpg)

Light says she feels deeply connected to Cruz when she’s in drag. Knowing that Cruz was a singer who genuinely loved what she did with a passion for her craft down to her final days bolsters Light with the energy she needs for her performances. Drag, she says, can be physically exhausting, requiring hourslong performances in heavy gowns and high heels, but it brings joy to her audiences.

“I am in a rare position where I go to work and I leave happier,” Light says. “I leave in a better place, I leave in a better mindset, I leave just happier. I feel like that’s how [Cruz] was, she loved singing, and it goes to show that your dreams don’t have an end date, they don’t have an expiration.”

“Entertainment Nation” goes on view at the National Museum of American History beginning December 9, 2022.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(800x602:801x603)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/74/f7/74f74bca-6ef7-4be6-98e7-a657e078f226/gettyceliacruz.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jacquelyne_Germain_thumbnail_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Jacquelyne_Germain_thumbnail_1.png)