The Epic Failure of Thomas Edison’s Talking Doll

Expensive, heavy, non-functioning and a little scary looking, the doll created by America’s hero-inventor was a commercial flop

:focal(520x127:521x128)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/66/6466ada1-09b2-4973-8e1c-145970bbf962/edisontalkingbabydolljn20143598web.jpg)

Editor’s Note, December 18, 2020: A new Smithsonian Sidedoor podcast revisits the peculiar story of Thomas Edison’s failed attempt to invent a talking doll, this time with an imaginary holiday twist, so we’re recycling our legacy article from 2015 when Edison’s doll first went on view in the exhibition “American Enterprise” at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History.

Spilled milk did not interest Thomas Edison. “I have spilled lots of it,” the prolific American hero-inventor wrote in 1911, “and while I have felt it for days, it is quickly forgotten.”

Almost a century after his death, little about Edison is in danger of being forgotten—including his moments of metaphorically spilled milk. The archives at Thomas Edison National Historical Park in New Jersey contain approximately 5 million pages of original documents of Edison’s epic successes in the realms of sound recording, motion pictures and electric power—and his failures—ventures into ore mines, cement houses, electric pens and talking toys.

When the new permanent exhibition “American Enterprise,” opens July 1 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., Edison’s 1879 incandescent bulb, the popular emblem of his 69-year career as an inventor, will be presented alongside one of his most intriguing failures—his 1890 talking doll. With 600 artifacts on display, the exhibition explores the history of business and innovation from the mid-1700s to the present, and in that chronicle the Edison doll, a commercial flop, testifies to the failures that attend and often outnumber the successes. According to Peter Liebhold, one of the show's curators, “The doll represents failure by one of the deities of invention.” When all was said and done, Edison called the dolls his “little monsters.” Liebhold, for whom they tell an essential story of the complexities and difficulties that lurk behind invention and innovation, calls the doll a “glorious failure.”

In this episode of Sidedoor, we’ll hear a short story that imagines what happens when two little girls receive one of Edison’s talking dolls as a holiday gift.

"Our lives, today, are saturated with sounds that have been previously recorded. It’s everywhere," says the museum's Carlene Stephens, who specializes in technology. “It is almost impossible for a 21st-century person to imagine a time when there was no such thing as recorded sound.” But there was. And in 1877 and at the age of 30, Edison, with his tin-foil phonograph, broke that particular “sound barrier,” producing for the first time—ever—sound that had been recorded and then played back.

Then, as now, extensions and applications of the new technology held the promise of social benefit and profit but posed problems. Although Edison identified toys as one way to exploit his phonograph’s entertainment potential, the unstable tin-foil recording surface was not commercially viable. It took both the development of wax cylinder sound recording by, among others, Alexander Graham Bell and Edison’s own improvements to the technology before the innovation narrowed into a commercial focus: he and his associates would manufacture talking dolls.

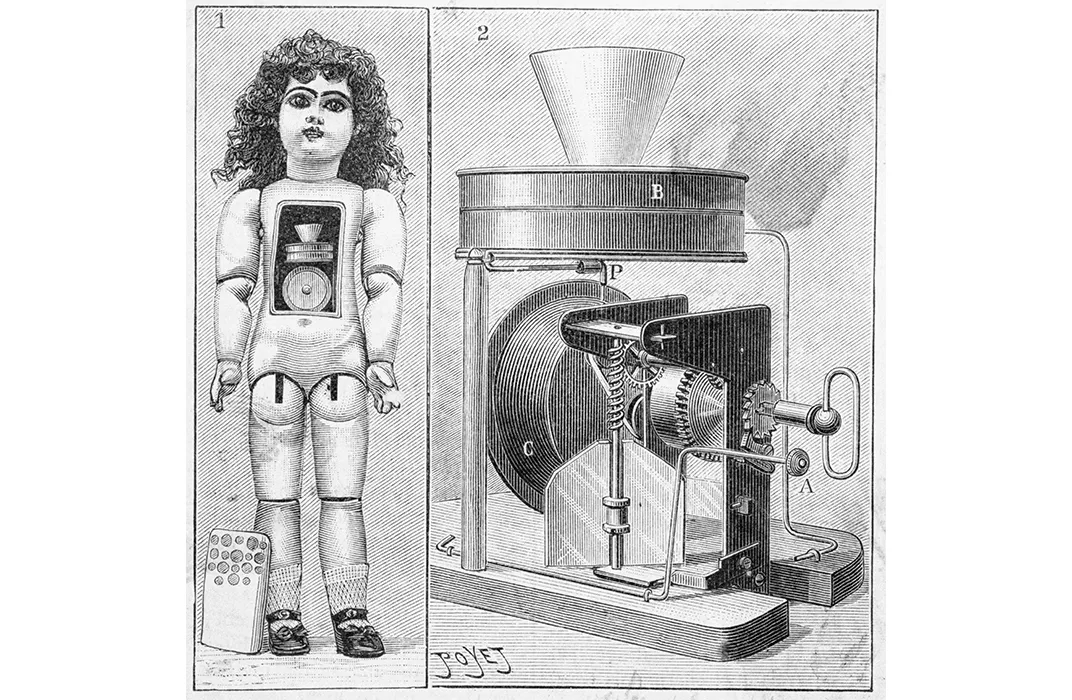

In early April 1890, each doll that emerged from Edison’s vast West Orange, New Jersey, site stood 22’ inches tall, weighed a heavy four pounds, and sported a porcelain head and jointed wooden limbs. Embedded in each doll’s tin torso was a miniaturized model of his phonograph, its conical horn trained toward a series of perforations in the doll’s chest, its wax recording surface etched with a 20-second rendition of one of a dozen rhymes, among them “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” “Jack and Jill” and “Hickory Dickory Dock.” With the steady rotation of a hand crank located on the doll’s back, a child could summon from the doll a single nursery rhyme.

It was a milestone: Edison’s talking doll marked the first attempt to reproduce sound for commercial and entertainment purposes. It is also the first known instance of individuals employed as recording artists—possibly as many as 18 young women working in factory cubicles, loudly reciting into machines, producing for each doll a single separate recording.

And it fell flat.

As quickly as the dolls left the West Orange site, complaints returned: the crank was easily misplaced, the stylus easily dislodged from its carriage, the wax record prone to breakage, and the sound fidelity poor. “We are having quite a number of your dolls returned to us and should think something was wrong,” a representative from Horace Partridge & Co. a Boston toy purveyor, wrote to Edison’s toy venture, in April 1890. “We have had five or six recently sent back some on account of the works being loose inside, and others won't talk and one party from Salem sent one back stating that after using it for an hour it kept growing fainter until finally it could not be understood.”

By May, mere weeks after the dolls’ launch, Edison withdrew it from the market. Precisely how many dolls were sold remains a mystery. By one estimate, as many as 2,560 dolls may have been shipped from the West Orange facility during that short period; conservative estimates suggest fewer than 500 actually sold to customers; today, an Edison Doll is a rare treasure. Little is known about the one held in the museum's collections, except that it was donated in 1937 by Mrs. Mary Mead Sturges of Washington, D.C.

Edison’ business records indicate that 7,500 fully assembled dolls remained on hand, stored in a packing room on the West Orange compound, with several hundred cases of imported doll parts at the ready. What had been optimistically heralded in one 1888 newspaper headline as “The Wonderful Toys Which Mr. Edison is Making For Nice Little Girls" was condemned two years later, in another newspaper, for the “flat, uninflected whine” of the recorded words. A Washington Post headline announced, “Dolls That Talk: They Would Be More Entertaining if You Could Understand What They Say.”

Edison, passionate about solving technical problems, promptly resolved to produce an improved version of the doll. But the force of his skills and determination were not enough to overcome a basic oversight: The marketplace. The doll’s price—ranging from $10 for an undressed doll to $20 for a dressed one—was too high. (By comparison, the 2015 equivalent of those prices would be $237 and $574.) “Fundamentally, I don’t think Edison understood consumer markets all that well,” says Paul Israel, director and general editor of The Edison Papers at Rutgers University and author of Edison: A Life of Invention. “He was much better at producing technology marketed by either others or for other producers.”

The doll was the first of Edison’s phonograph technologies to be developed for the consumer market—and it was an area he had little aptitude or appreciation for. “From his experimental failures Edison sees ways to learn, to gain knowledge,” Israel says. “But commercial failures, of which the toy doll was clearly one, sometimes they don’t really go anywhere. One doesn’t get the sense that Edison, other than for a brief period, comes away from that venture thinking, ‘Why did this fail? Marketing? Economics?’ He just never pursues those kinds of investigations.”

By the fall of 1890, despite Edison’s resolve to redesign the doll, the Edison Phonograph Toy Manufacturing Company, more than $50,000 in debt, was unable to secure a loan to manufacture an improved second-generation doll. Edison, characteristically optimistic, moved on.

"The doll had a brief moment of being a brilliant idea and it failed commercially,” Stephens says. Edison’s doll was an experiment that needed refinement, but in the commercial world, timing is essential. “Sometimes the saying ‘first in, wins’ holds true, and sometimes ‘first in’ means that you show all your flaws and somebody else comes along later and makes the improvements.”

Stephens points to Apple’s smartwatch as a contemporary example of Edison’s effort to integrate a new technology—his phonograph—with an old one—the doll. “Sometimes it works,” she says, ”and sometimes it doesn’t.”

The new permanent exhibition “American Enterprise,” opened July 1 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. and traces the development of the United States from a small dependent agricultural nation to one of the world's largest economies.

American Enterprise: A History of Business in America