Esperanza Spalding: Jazz Musician, Grammy Award Winner and Now Museum Curator

The title of her latest album “D + Evolution” is also the theme of a new exhibition at the Smithsonian’s Cooper Hewitt

:focal(1076x1360:1077x1361)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f5/b4/f5b45838-8dcb-4357-83fd-88b63516fbb2/8920162.jpg)

Esperanza Spalding resists categorization. She is an accomplished jazz bassist and composer with an omnivorous interest in musical experimentation: Her five solo albums and numerous collaborations incorporate funk, soul and other genres.

The 32-year-old, four-time Grammy winner is comfortable performing alongside both Top 40 pop stars and grizzled jazz pros. She also seems equally at home in a hole-in-the-wall club as she is at the White House. Spalding’s approach has led her to embrace a wide range of styles on her own terms, and she has a deep appreciation of the capacity of one genre to feed off another and create something new.

When it comes to music and art, Spalding believes that evolution in one direction grows out of the devolution of another form, and vice versa. Progress and regress are not mutually exclusive, but they are essential to one another. All Spalding needed was a way to explain it.

“I was trying to come up with a phrase to describe what I was experiencing and observing,” she says. “Maybe devolution is a necessary function of evolution—one doesn’t have to diminish the other. They can coexist.”

The term Spalding settled on was “d+evolution” (pronounced “d plus evolution”). It’s a concept that pervades much of her music—even before she had a name for it—and provided both the title of her latest album and the theme of a new exhibition she curated at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f8/1d/f81d4be4-11fa-4cbd-881e-ecf3fd07a44a/14_esperanza-054.jpg)

“Esperanza Spalding Selects” enabled the singer to explore the museum’s vast collections and choose a handful of pieces for the show. Through the almost 40 objects Spalding selected, and several that she helped to create, the artist explored how a person, object or idea can simultaneously evolve and devolve.

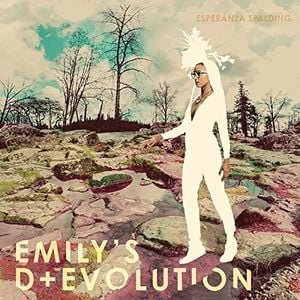

It’s hardly a surprise that Spalding focused on this concept for the show. When she began the early planning stages of the “Selects” exhibition, Spalding was on tour promoting her latest album, Emily’s D+Evolution. Its 12 tracks are performed from the perspective of Emily, an extroverted alter ego (the artist’s middle name serves as her moniker) who provides the singer with a distinctly separate persona. Spalding’s penchant for experimentation was apparent throughout the tour, with acts incorporating both theatrical and jazz segments.

“I was like, ‘I can’t do any other project. I’m too immersed in this,’ so I said, ‘What do you think about d+evolution?’” she says. “As it turns out, that theme does live in other types of creation, and there is a real history of d+evolution in these objects.”

Spalding found that in almost every design tradition, the same state of flux is present. As she writes in the exhibition’s brochure, “design does not progress in a straight line. Design grows in response to the same essential forces of breaking down and building up that inform all innovation. All of these objects reflect a juncture in design where previously held values, forms, and relationships broke down as their new iterations emerged.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/59/8d/598d745c-7fcc-4bc8-a957-d3853231c918/img_0043.jpg)

The singer joined museum curators on a visit to the Cooper Hewitt’s storage facility in Newark, New Jersey. There, curators pointed out potential objects or categories of objects that might express Spalding’s vision.

“We were hunting for objects that had a story that would support this theme,” Spalding says. “The curators were much more intimate with the stories of these objects, so they presented tons of things, most of which did not really do it for what d+evolution means for me.”

But in the hours-long process of searching, the group came across an item that captured Spalding’s vision perfectly—a handmade purse. Floral-patterned leather wall paneling in Holland had been repurposed as decorative shipping boxes that were sent to Japan, which were further modified to create the purse.

“That’s a very concise example of one entity getting deconstructed and along the way evolving, even as it’s literally devolving from its original use and function,” Spalding explains. “And in value, too, it’s garbage [as discarded wall paneling] becoming a new object as a box, [and] then the discarded box becomes a whole new object as the purse.”

Some objects express the exhibition’s theme when viewed alongside other artifacts. This is the case with a series of sheet music cover designs that represent shifting characterizations of African-American and indigenous individuals, as well as musical traditions (Spalding’s father is African-American, and her mother is of Native American and Hispanic descent.). A 1931 cover for Fox-Trot’s song “Quit Cryin’ the Blues” shows a racist caricature of an African-American man, while a 1934 cover for Duke Ellington’s “Solitude” presents an elegant depiction of the African-American musician just three years later.

“It’s cultural stereotyping devolving over time,” Spalding says. “It’s a testament to the fact that our cultural expectations have evolved, and in the process [the early depictions] have devolved.”

The singer took her idea a step further by “d+evolving” one of the songs included in the show. She performed it straight through, created an improvised version and made a vocal interpretation of that improvisation. Jazz keyboardist and composer Leo Genovese, a frequent collaborator, reconstructed the tracks into an entirely new song with added piano elements. All of these versions are played on a continuous loop in the show.

“We proactively did some d+evolution,” Spalding says.

Emily's D+Evolution

Esperanza Spalding presents her latest project Emily's D+Evolution a rekindling of her childhood interest in theater, poetry and movement, which delves into a broader concept of performance. Taking a new approach to her on-stage persona, the remarkable Spalding taps into new creative energy, delivering musical vignettes inspired during a "sleepless night of full moon inspiration." As she puts it, "Emily is my middle name, and I'm using this fresh persona as my inner navigator. This project is about going back and reclaiming un-cultivated curiosity, and using it as a compass to move forward and expand. My hope for this group is to create a world around each song, there are a lot of juicy themes and stories in the music. We will be staging the songs as much as we play them, using characters, video, and the movement of our bodies."

Spalding had gathered a collection that approached what she sought for the exhibition, but it was not quite there. Her name was in the title of the show, and she wanted more of her personality and musical influences to shine through.

The artist was concerned that although the objects worked well on their own or in “families,” the exhibition didn’t have the overall coherence or musical connection she was seeking.

“I was worried that somebody walking in wouldn’t make the connection,” she says. “So I said, ‘What if we just got a piano and exploded it, and created new objects that supported it throughout the room?’”

To fully realize her vision for “Selects,” Spalding brought in additional artists. They created original works that use pianos to illustrate the eight forms of d+evolution in the show. The singer asked salvage artist and fellow Portlander Megan McGeorge to acquire the pianos and worked with Robert Petty of ZGF Architects to devise the designs.

“I thought if we took a familiar object and showed it in some frozen states of d+evolution, it might help express the idea,” says Spalding.

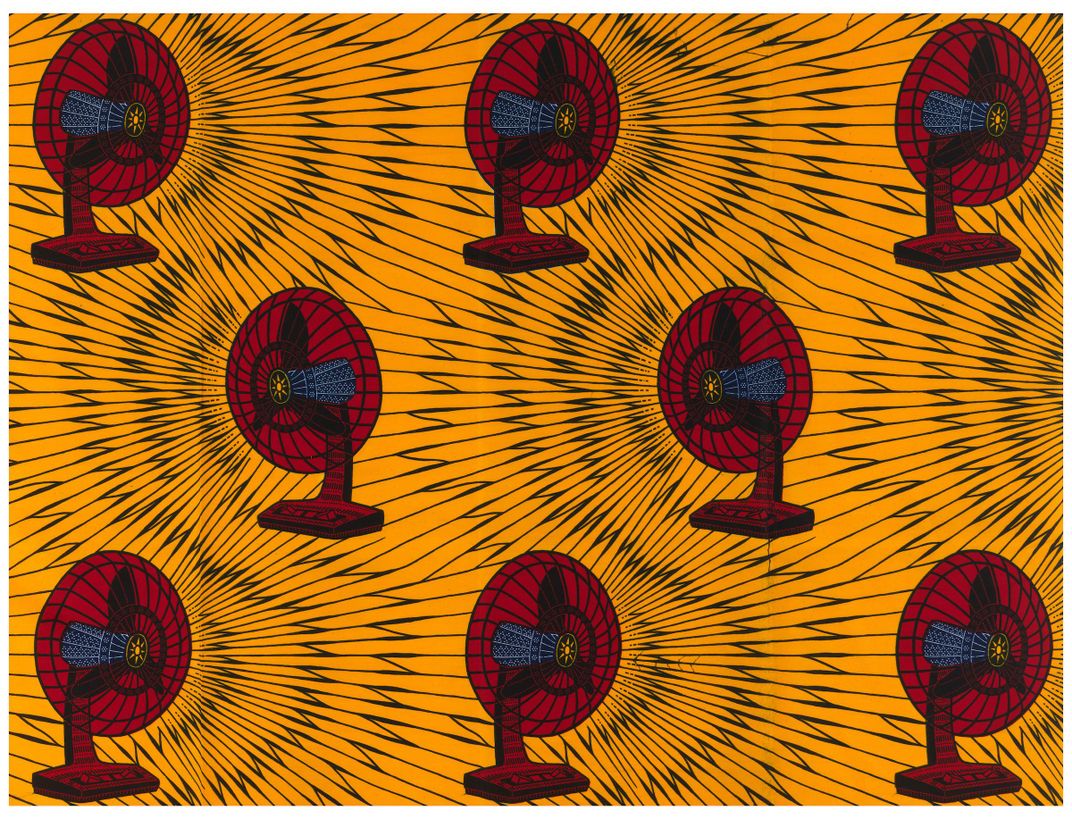

Parts of a piano complement a section of the show focused on textiles, questioning the assumption that evolution means “more advanced.” The display includes textiles from early 20th-century Parisian fashion designer Paul Poiret, who hired girls untrained as artists to sketch impressions of plants and animals. These images were then turned into drapery, carpet and wall coverings.

An area of seemingly practical objects that were designed “beyond functionality” (including Fernando Campana’s Trans…Armchair, a wicker chair into which the Brazilian artist has inserted discarded plastic and rubber objects) takes inner pieces of a piano and showcases their structural—if rarely appreciated—beauty as part of a swooping sculpture where they take on the appearance of flocking birds or a wave.

“[The artists] are showcasing the design of each mechanism inside the piano and have created a gorgeous new design,” Spalding says.

Although she enjoys moving between personas and styles, Spalding admits that taking on the role of curator presented particular challenges.

“I’m not used to having to explain myself so much—when you write a poem or composition or song, it’s all in the song. Listen to the song, [and] you’ll get it,” she says. “I’m a musician, not a curator, but this has been great practice of reducing big ideas into digestible chunks.”

“Esperanza Spalding Selects,” is on view at the Cooper-Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum through January 7, 2018. The museum is located at 2 East 91st Street (between 5th and Madison Avenues) in New York City.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/64/a5/64a50c11-5d8a-4ea2-b16f-9559708e5168/8920164_gods_trombones_2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/02/7d/027d7a0f-c753-4240-83d1-59f88d1a8f15/89201613.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/99/d8/99d8216a-d8ba-4864-aba7-3ea9d94eba48/1931-48-73.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/94/b494042a-8c47-48d8-a320-8dc1be5cf8c1/90645_23db3aad1a13b481_b.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)