Every Year Just ‘Bout This Time, Kurtis Blow Celebrates With a Rhyme

In a salute to “Christmas Rappin,’” hip-hop chronicler Bill Adler tells the tale of how the famous rap recording came to life

:focal(1485x528:1486x529)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/78/b1/78b15a24-1a62-4a6e-a0af-95a460ceae03/gettyimages-579212436.jpg)

It begins with a tony-sounding English gent reciting the opening lines of Clement Clark Moore’s “Twas the Night Before Christmas.” The Brit gets exactly ten words into the holiday standard before being rudely interrupted. That was the moment, 40 years ago this month, when the 20-year-old African-American rapper Kurtis Blow made his debut on wax.

“Hold it now! Hold it—that’s played out!” Blow shouts at the twit. The rapper then turns to his band, instructs them to “Hit it!” and, as the beat drops like a punch to the gut, young Mr. Blow spells out the seeds of his impatience:

Don’t ya give me all that jive

‘bout things you wrote before I was alive

‘cause this ain’t Eighteen twenty-three

Ain’t even Nineteen seventy

Now I’m the guy named Kurtis Blow

And Christmas is one thing I know

So every year just about this time

I celebrate it with a rhyme.

And for the next three-and-a-half minutes, Blow unspools a story about Santa stopping in Harlem to drop off some gifts on Christmas Eve, then deciding to hang out and party with the gang of young people he meets on the premises. Tradition? It was a new day.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/9d/28/9d282338-e0d8-40cc-9054-0afc7642b4c2/gettyimages-74254813.jpg)

Although Blow’s “Christmas Rappin’” was one of the very first rap records ever to see the light of day, in retrospect, the brash confidence was quintessentially hip-hop. And, as is true of hip-hop more generally, that presumptuousness turned out to be entirely justified. Four decades after the song’s release, the story behind its enduring success is a tale worth telling.

It was the spring of 1979 when a wanna-be record producer named Robert Ford, known as Rocky to his friends, got his girlfriend pregnant. Soon to turn 30, Ford was working as a reporter and reviewer for Billboard magazine, a job he loved that paid him maybe $300 a week. It was just enough to keep his nose above water, but hardly enough to support a child. An honorable young man, Ford knew he had to do the right thing. “I’d promised my father that I was gonna take care of any kid that I brought into this world,” he recalls. So, he thought, how could he conjure up the necessary dough?

That’s when lightning struck, Ford decided he’d make a Christmas rap record. So what if no one had ever made a rap record before? So what if the mainstream music industry cared nothing about rap? So what if the earthshaking success of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight” was still a few months down the road?

It just so happened that Ford worked alongside an older guy named Mickey Addy, who’d written a Christmas record for Perry Como in 1951, and who swore that you could always make money on a Christmas song because it plays every year, year after year, no matter what.

“So,” says Ford, “that was my inspiration.”

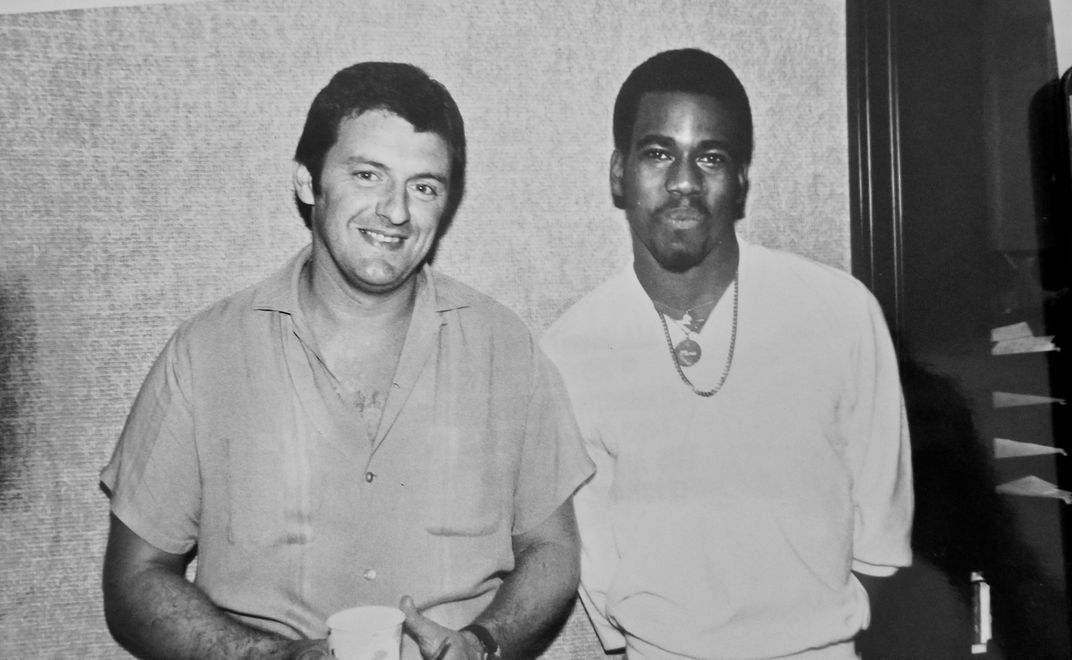

Ford shared this dream with his music-loving colleague at Billboard, J.B. Moore (no direct relation to the author of “The Night Before Christmas”). “Robert was a black guy from the middle of Hollis, Queens, and I was a white guy from the north shore of Long Island, and our record collections were virtually identical,” J.B. Moore recalled in a 2001 interview.

Moore loved the idea of a Christmas rap record, so much so that he steamed ahead and wrote some rhymes without telling Ford, who discovered Moore’s efforts when he got home from work one night and played a message on his answering machine from Moore reciting some verses he’d written for “Christmas Rappin.’”

“I heard them and I said, “That’s it!” he recalls.

After Ford embraced his lyrics, Moore volunteered to pay for the record’s production. For the previous five years, the 37-year-old Vietnam vet had been setting aside money, week-by-week, building his nest egg. His dream was to leave Billboard so that he could devote himself to the writing of a novel about his time in Vietnam. Now, with a savings of about $10,000, Moore decided instead to plunk it all down on “Christmas Rappin.’”

With the lyrics written and the money to produce it in hand, the question remained: Which of the hottest emcees of the day would do the rapping? Ford’s first choice was DJ Hollywood. Like Kool DJ Herc, Hollywood was one of hip-hop’s founding deejays. In fact, he started doing his thing in 1972, a year before Herc jumped into the game. Ford’s second choice was Eddie Cheeba. A student of Hollywood, Cheeba was in demand at hardcore hip-hop venues like Disco Fever in the Bronx and at more upscale spots like the Charles Gallery in Harlem.

Ford was still trying to settle on a choice when he took a bus ride down Jamaica Avenue in Queens one day. His eye happened to fall on a young man posting flyers for a rap show. The kid—Joey Simmons, was his name—told Ford that the show was being produced by his older brother Russell. Ford gave the promoter a call.

Russell Simmons in the flesh turned out to be a one-man hip-hop whirlwind. A 21-year-old native of Hollis, Queens—the same community where Ford had grown up—Simmons was nominally a sociology major at the City College of New York. But the majority of his time was spent producing and promoting hip-hop parties—a budding entrepreneurship at which he was supernaturally good.

The energy radiating from Simmons, including his non-stop motor-mouthing, had long since earned him the nickname Rush. His work, conducted under the banner of Rush Productions, was then a three-man partnership. Besides Rush, this team included an older friend named Rudy Toppin and a 19-year-old rapper—and fellow City College student—who went by the name of Kurtis Blow.

Blow—born Kurtis Walker—was a talented and ambitious young Harlemite whose first role model was the actor, singer and civil rights activist Paul Robeson. “Robeson was multi-talented so I plotted my life to be like that,” he says. The young man’s ambitions sharpened as a teenager after he discovered the multi-genre culture of hip-hop. A few years later, as a communications major at City College, Blow decided to concentrate on rap, even as he and Simmons continued to promote parties together.

Then, late in the summer of 1979, Ford confided to Simmons his plan to make a rap record. Simmons promptly hatched a plan of his own: to showcase Blow at the Hotel Diplomat in Times Square. And on that night, August 31, 1979, Ford was sure enough in the house, and ended up agreeing that Blow was the right man for the job. The decision, he said, was a two-fer: Russell Simmons came along with Kurt Blow. “Russell had a lot of energy and he understood how to get paid better than anybody I’d ever met,” Ford says.

The squad’s energies now turned to the making of the record. The question: How to replicate on record a kind of music that had never before been recorded? In a pre-production meeting with Ford, J.B. Moore and the musician/arrangers Denzil Miller and Larry Smith, Blow suggested that it might be a winning idea to combine, somehow, the heavy funk of James Brown with the genre-hopping disco of Chic, the New York-based crew whose “Good Times” was not only the number one radio hit in the city at the time, but enjoyed favor in hip-hop circles. The die was cast.

They convened at Greene Street Recording, a little studio situated in a changing part of lower Manhattan that just a few years earlier people had begun calling “Soho.” The musicians were a mix of J.B. Moore’s pals (drummer Jimmy Bralower) and Ford’s (Smith and Miller). Also present was Adam White. A young Brit, who worked with Ford and Moore at Billboard, White was enlisted to recite the beginning of "The Night Before Christmas." This was the crew waiting for Kurtis Blow when he walked in the door and Moore handed him a printout of the lyrics.

The rapper had never seen anything like them before. Forty years later, Blow still savors their strangeness:

He was roly, he was poly, and I said, “Holy moly!’

You gotta lotta whiskers on your chinny-chin-chin.”

He allowed he was proud of the hairy little crowd

on the point of his jaw where his skin shoulda been.

“That’s a totally different meter from the way we rapped then,” Blow says. “But it was so witty, and I welcomed the opportunity to do it.” Blow notes that he himself wrote the lyrics for the second half of the record—“about Santa Claus being in the party and there’s a whole big crowd and everyone’s having a great time.”

The recording was completed in a single night. Blow remembers cutting the entire eight-minute song as if it were being performed live in a club; he rapped, the band played along, the tape rolled, and they were done.

But even so, the finished product struck some folks at the time as a pretty iffy hybrid of mismatched body parts. “The challenge,” says music critic Nelson George, “was to reconcile these two worlds, between making a record and making a rap record, and what did that mean?”

Indeed, now came the hardest part—finding a label willing to issue the record. Ford recalls being turned down by nearly two-dozen firms before striking pay dirt at Mercury Records. The problem was that virtually no one at the major labels wanted anything at all to do with rap, even though by that time—October of 1979—the whole wide world was being rocked by the success of “Rappers Delight,” one of the first rap records ever made. “No one in midtown gave a f***,” says George. “And no one black in midtown really gave a f***.”

How to explain this industry-wide aversion? In an interview in 2001 Ford suggested that very few black professionals liked rap music then “because it reminded them of being in the ghetto.” And that at least partly explains how and why “Christmas Rappin’” was signed to Mercury Records by a white Englishman.

John Stainze was working in the A&R department of Phonogram’s London office, from which perch he’d signed Dire Straits, when he was offered the chance to do the same kind of work at the firm’s L.A. office. A lover of American R&B, Jamaican reggae and Christmas novelty records, Stainze jumped. It was there that he received a cassette from New York mailed to him by J.B. Moore. “I took a listen to it and felt, yeah, that’s pretty good,” he says.

He immediately undertook what turned out to be a fairly sustained campaign to sign the record. His colleagues in the office didn’t want anything to do with it and neither did the national head of Mercury’s R&B department—at first. But Stainze persisted and the doubters decided to take a shot.

Thanks to a couple of key innovations, “Christmas Rappin’” turned out to be a song for all seasons. The B-side of the seven-inch single released in the U.K. was an instrumental subtitled “Do It Yourself Rappin.’” It was a new feature, done deliberately to allow Kurtis Blow to perform the song live without having to rap over his recorded vocals. Indeed, every rap record from that point on included an instrumental version on the B-side.

The A-side of the 12-inch version—a full eight minutes long—started with J.B. Moore's rhymes about that red-suited dude with a friendly attitude, and then turned into a greatest hits compendium of the party rhymes Blow had been spitting during live shows for years. Club deejays all over the world always rocked the full-length version—except when Blow himself happened to be in the house. Then they’d play the instrumental.

“Christmas Rappin’” proceeded to make its mark in the U.K. and the U.S. It peaked at number 30 on the U.K. pop charts during the week of December 15, 1979. It never cracked the U.S. charts, but it was a street-level smash for a full eight months after Christmas, and ended up selling more than 350,000 copies, ten times more than Mercury’s original goal.

Naturally enough, the label exercised its option for a second single. Released in May of 1980, “The Breaks,” is an amusing rap about bad luck and good music that broke into the U.S. charts, peaking at number four on the R&B hit parade and number 87 on the Hot 100. It ended up selling more than 850,000 copies.

Well and truly launched, Kurtis Blow went on to record ten albums, and produce hit records for other rappers. He appeared in movies and stage musicals, hosted nationally syndicated radio shows and did high-level commercial endorsements. In recent years, photographs of Blow and some of his stage gear have been added to the collections of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African American History and Culture. A recording of "Christmas Rappin'" is housed at the National Museum of American History. The rapper celebrated his 60th birthday this past August, and he’s marking the 40th anniversary of “Christmas Rappin’” with an album’s worth of new Christmas recordings.

Robert Ford and J.B. Moore have likewise lived happily ever after. Their breakthrough success as the producers of Kurtis Blow’s first five albums opened up such opportunities as the chance to make “Rappin’ Rodney” for Rodney Dangerfield in 1983. Ford marked his 70th birthday in June of this year, the same month that his dear son Dobie (known more formally as Robert Ford III) turned 40.

As of the fall of this year, “Christmas Rappin’” had been sampled 181 times, including by the Beastie Boys, Public Enemy, Nas, Cypress Hill, J. Dilla, UGK, Raekwon, Onyx, Lil Kim, Redman, Busta Rhymes, House of Pain, Slick Rick, Schooly D, Mobb Deep, EPMD, LL Cool J, De La Soul, Naughty by Nature and MC 900 Ft. Jesus.

“Christmas Rappin’” remains Blow’s personal favorite of all of his records. “It opened up a whole new world, a whole new life,” he says. “Man, there was 40 years of that stuff! Incredible.”

Indeed, just as Mickey Addy insisted, a Christmas record is the gift that keeps on giving.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ba_best_benabib_portrait.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/ba_best_benabib_portrait.jpg)