Evoking a Ship’s Rippling Sail, This New Sculpture Aims to Make Global Connections

The African Art Museum at its first award ceremony recognizes two international artists who have overcome personal hardships to excel

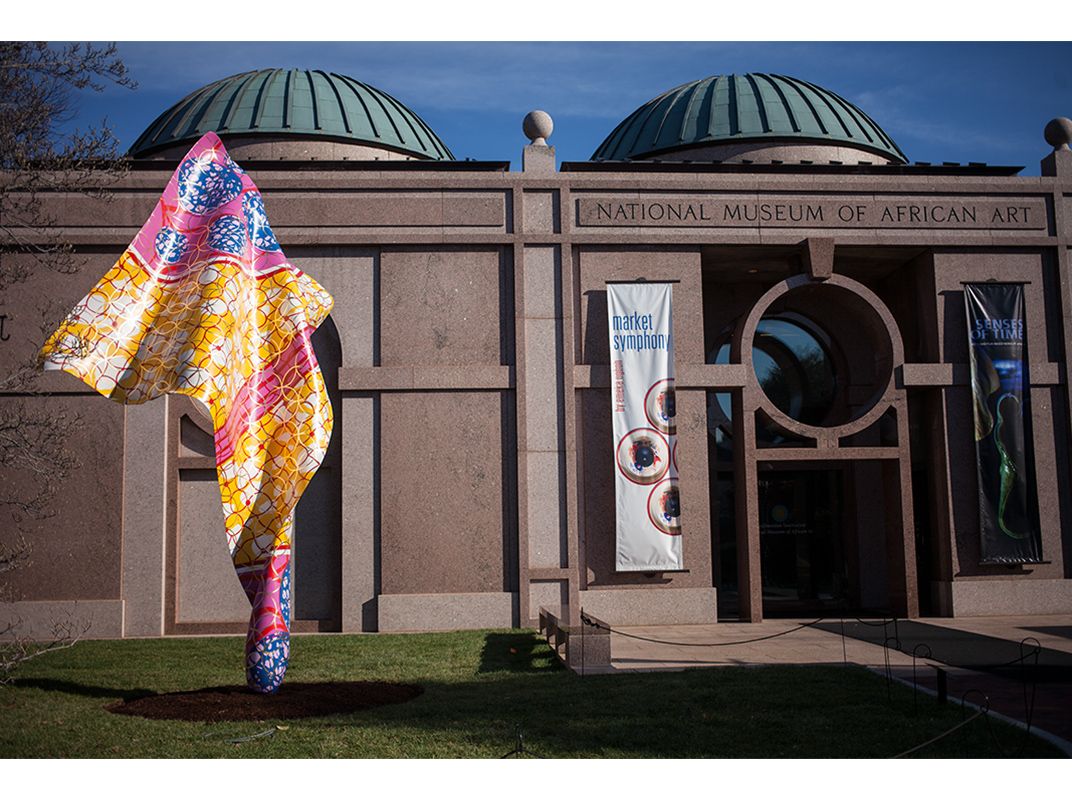

When Yinka Shonibare’s Wind Sculpture VII was unveiled outside the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art this month, it had the visual effect of a colorful mast rippling in the wind.

That, however, is an illusion: The 21-foot, nearly 900-pound work is made of fiberglass over steel. The artwork is meant to suggest "that the opening of the seas led not only to the slave trade and colonization but also to the dynamic contributions of Africans and African heritage worldwide," says the museum.

Shonibare’s works often create cultural commentary by draping iconic colonial and Western European scenes in the eye-popping color and dancing patterns associated with African garb.

But that, too, is an illusion. Designs that are often considered to be African in origin are patterns that actually emerged in Indonesia, but were manufactured by the Dutch and shipped to markets in West Africa, which took to them strongly enough so that they have become associated with Africa ever since.

The complicated connections between assumed cultural representations is central to the work of Shonibare, a British artist raised in Nigeria, who received a mid-career retrospective at the National Museum of African Art in 2009 to 10.

Shonibare, 54, returned earlier this fall to the museum to receive the institution's first African Art Award for lifetime achievement.

The other artist honored at the event was Ato Malinda, 35, of Rotterdam, who earlier this year received a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship. In addition to dealing with issues of race and culture, Malinda also addresses feminism and the plight of the LGBTQ communities in Africa with performance pieces that have landed her in jail.

At the gala African Awards Dinner October 28 in the Smithsonian’s sprawling old Arts & Industry Building, the two artists expressed gratitude for the recognition while reflecting on their personal struggles.

“I’m a little bit overwhelmed,” Shonibare told the crowd. “This has been a long journey for me. “

He was 19 and in college when he contracted transverse myelitis, an inflammation of the spinal cord.

“I remember lying in bed completely paralyzed,” Shonibare said. “At the time, the doctors didn’t know what I was going to do with my life. My parents were told not to expect too much. I have since gone beyond any expectations.”

Indeed, he has exhibited at the Venice Biennial, was shortlisted for the Turner Prize the same year he was awarded an MBE, or Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.

“The power of art is transformative. My art literally saved my life,” Shonibare said.

It also gave him a cause. “My own mission from the beginning was to make my art be a way, a source for reconciliation. How then do we turn dark into light? With art this is possible.”

Malinda, for her part, received much notice for an art career in performance and other media, but was at the point of rethinking her choices especially after the death of a loved one in spring.

“I was filled with artistic angst, and wondering if I was doing the right thing with my life which no doubt came from witnessing death,” she said in a speech in which she was briefly overcome with emotion.

Just then, she said, “I received the most inspired and and kind letter from Dr. Cole.”

The notice from museum director Johnnetta Betsch Cole that she had been given the Institution's Artist Research Fellowship—and now the African Arts Award—are just the kinds of encouragements to keep her going.

“I honestly feel like they’re saying, ‘What you’re doing, we’re listening and please continue,’” Malinda said in an interview. “Because I come from a family that never supported my career choice, it’s really quite amazing to be honored like this.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3d/b3/3db3140c-0dd8-483f-9519-d0f09df22e90/4-wind_sculpture_vii.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)