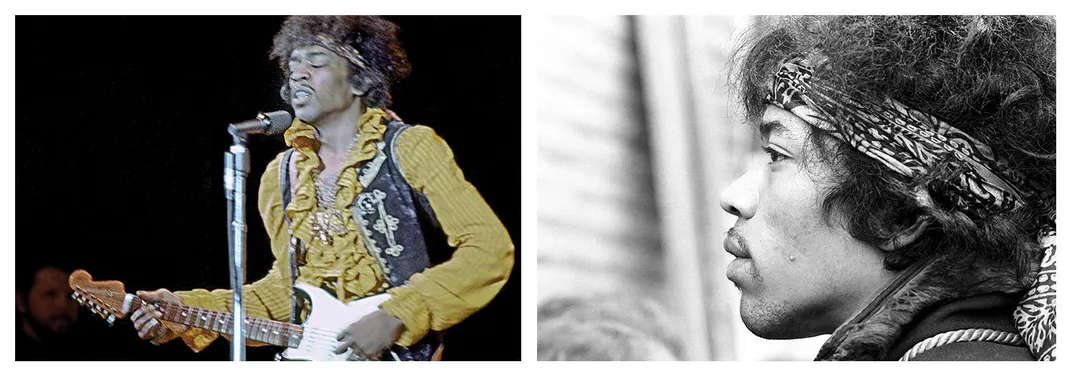

The Exotic Vest That Introduced America to Jimi Hendrix

The fashionable garment conjures the guitarist’s dazzling performance at the Monterey County Fairgrounds

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/67/e8/67e87158-72e5-4a6b-a52f-1155fe17770e/opener.jpg)

A crowd estimated in the tens of thousands gathered at the Monterey County Fairgrounds in Northern California in June 1967 for the Monterey International Pop Festival, a three-day extravaganza. Today the festival is considered a kind of informal opening ceremony for the Summer of Love: A new, liberated ideology was taking hold in the culture, and here was its soundtrack. “The Monterey Pop Fest introduced the mushrooming counterculture to the world,” Holly George-Warren, the author of Janis: Her Life and Music and co-author of The Road to Woodstock, told me. “It sowed the seeds for Woodstock, and so many festivals to follow.”

The lineup included the Grateful Dead, the Who, Otis Redding, Ravi Shankar and Jefferson Airplane, but the breakout performance came from a young American guitarist named Jimi Hendrix, who was making his first major appearance in the United States. Hendrix had recently released his debut LP, Are You Experienced, but the album wouldn’t crack Billboard’s Top 10 until the following year. The Monterey organizers had booked him on the recommendation of Paul McCartney, but few people in the crowd knew who Hendrix was or what he could do.

A few days before his performance, Hendrix visited Nepenthe, a bohemian restaurant 800 feet above the Pacific Ocean, overlooking the Santa Lucia Mountains in Big Sur, California. While at Nepenthe, Hendrix did some shopping at an adjacent store, the Phoenix, which sold all sorts of exotic clothes, including velvet vests from Central Asian countries like Afghanistan. It’s not certain, but Hendrix may have purchased the black vest he wore that weekend during his performance at Monterey, and this burgundy velvet version in a similar style, now in a Smithsonian collection. Even today, more than half a century later, it’s still recognizable as pure Hendrix—colorful, extravagant, audacious.

His aesthetic ran to rich, unexpected embellishments drawn from startlingly disparate sources: ruffled blouses, patterned bell-bottoms, jeweled medallions, brooches, silk scarves, rings, headbands and sometimes even a cowboy hat. For his Monterey performance, Hendrix wore a black vest over a ruffled, canary-yellow blouse, with red bell-bottoms and black boots. In a 1967 interview with the German radio D.J. Hans Carl Schmidt, Hendrix suggested that his style was mostly directed by an internal sense of cool: “[I’ll wear] anything I see that I like, regardless of what it looks like, and regardless of what it costs.”

He applied a similar sensibility to his sound, which drew from electric blues, hard rock and R&B. I often wonder what it must have been like to see Hendrix play that Sunday—whether it felt like watching something being invented right in front of you. He was already developing his own musical grammar, reliant on tone-altering pedals and the then-radical idea that feedback and distortion could be as useful and evocative as a cleanly played note. His Monterey performance was career-making, revolutionary. He opened with a cover of Howlin’ Wolf’s “Killing Floor,” a raucous, vaguely remorseful song about staying in a volatile relationship, and closed with a cover of the Troggs’ “Wild Thing,” a pure celebration of youthful debauchery. “Hendrix came across like a psychedelic sexy shaman, blowing the audience’s mind,” George-Warren said.

In September 1970, in the last interview he gave before his death later that month at age 27 following a barbiturate overdose, Hendrix was dismissive of the elaborate outfits he’d become known for. In retrospect, the disavowal feels like a portent: “I look around at new groups like Cactus and Mountain and they’re into those same things with the hair and the clothes—wearing all the jewelry and strangling themselves with beads,” he told a British journalist, Keith Altman. “I got out of that because I felt I was being too loud visually. I got the feeling maybe too many people were coming to look and not enough to listen.” There were extraordinary and unexpected pressures in being so thoroughly and relentlessly scrutinized—and Hendrix felt them.

Yet in the Monterey footage three years earlier, Hendrix revels in being seen. Toward the end of “Wild Thing,” he empties a bottle of lighter fluid onto his guitar, kisses it goodbye and sets it ablaze while gyrating his hips. The light from the flames bounces off the metallic threads of his vest, and Hendrix appears, briefly, as if he is wearing not clothing but a constellation, and for a moment is not bound by our world.