Why the Experimental Nazi Aircraft Known as the Horten Never Took Off

The unique design of the flyer, held in the collections of the Smithsonian, has infatuated aviation enthusiasts for decades

:focal(1599x971:1600x972)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1d/08/1d0843a9-5342-4da9-be70-17666c643a7a/mar2020_b01_prologue.jpg)

In the years after World War I, when aviation was all the rage in Europe and North America but the Treaty of Versailles banned the production of military aircraft in Germany, glider clubs sprang up across the country. The brothers Walter and Reimar Horten, just 13 and 10 years old, respectively, joined the Bonn glider club in 1925, and soon turned from flying kites to a far more ambitious activity—experimenting on a futuristic, tail-less aircraft known as a flying wing.

The idea was not unprecedented; the German aerospace engineer Hugo Junkers had patented a flying-wing design in 1910. The concept is that an airplane’s fuselage and tail, while they provide lateral control, add a great deal of weight and drag and do not contribute to lift. A flying wing, without those appendages, would be vastly more efficient and thus travel farther, if it could be controlled. The Horten boys kept tinkering, and by 1932 had developed an all-wing glider, made largely of wood and linen, that actually got off the ground—though it had some stability problems.

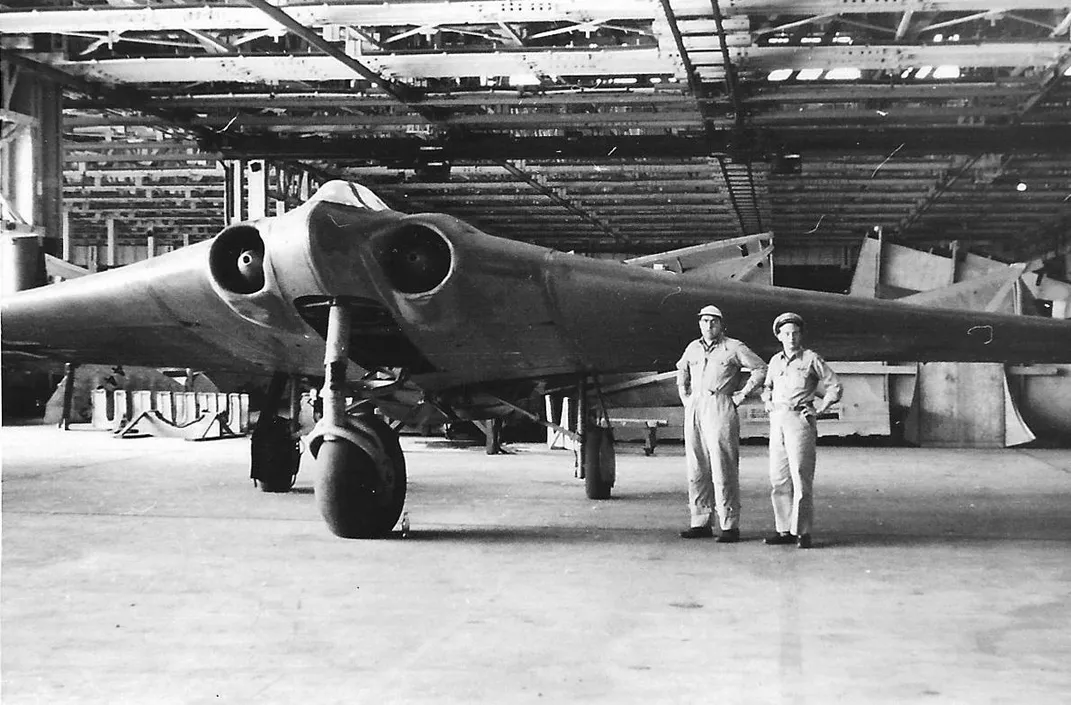

In 1943, when Nazi field marshal Hermann Göring demanded that the Luftwaffe’s next bomber aircraft be able to carry a 1,000-kilogram bomb load 1,000 kilometers into enemy territory at a speed of 1,000 kilometers per hour, the Horten brothers presented him with plans for a jet-powered, single-pilot flying wing. Its steel framework was covered in a plywood skin, and the wings were finished in a green protective coating. Göring awarded the brothers half a million reichsmarks to develop a long-range bomber, called the Ho 229. Their first prototype, an unpowered glider, had a successful test flight in 1944, and a second, jet engine-powered prototype took to the air the following year, establishing that a powered flying wing could be controlled in flight. In light of that feat, it’s possible the third prototype, the Ho 229 V3, would have flown farther than any aircraft of its day.

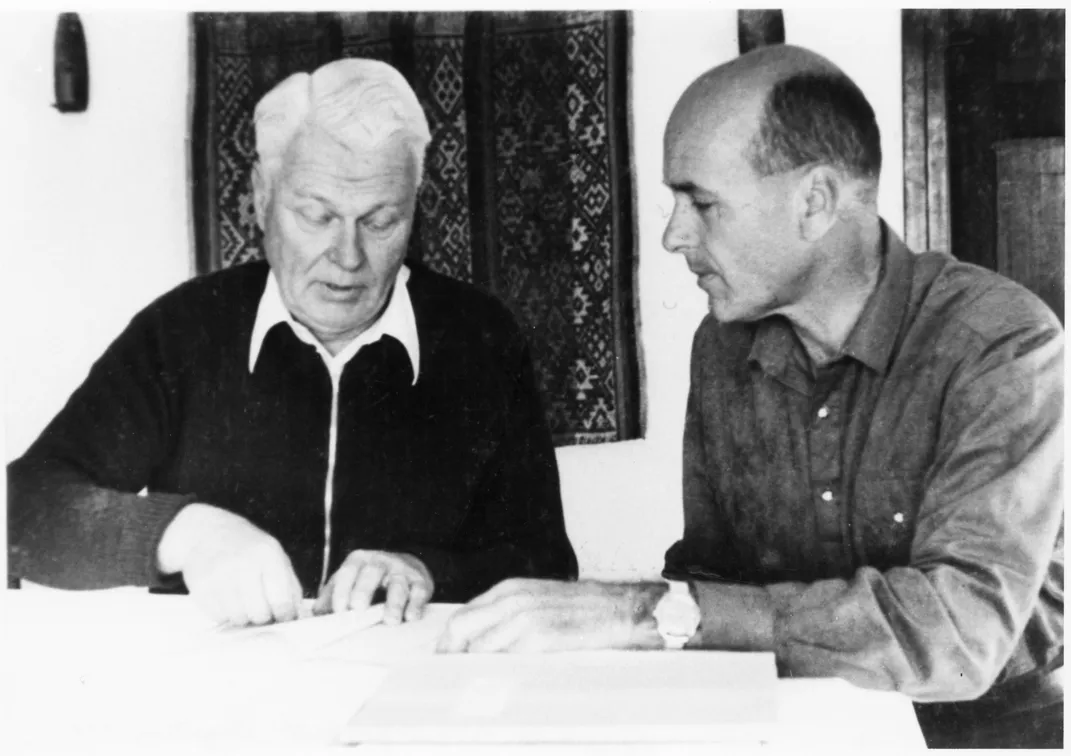

Instead, by April 1945, Gen. George Patton’s Third Army had recovered the V3 during Operation Paperclip, an effort to capture German intelligence and keep it from the Soviets. The Allies brought the Horten brothers to London for questioning. Following the war, Reimar failed to find consistent work at aerospace companies in Britain before returning to Germany, where he obtained a doctorate in mathematics; he spent the rest of his life working on aircraft in Argentina. Walter, back in Germany, joined the new, postwar Luftwaffe.

The V3 prototype, meanwhile, was shuttled from Germany to France to the United States, reaching the Smithsonian around 1952. While it sat in storage for decades, it became an object of gossip and fascination. Some aviation enthusiasts have posited that if the war had gone on longer, the Germans could have used the Hortens’ designs to achieve the first stealth bomber. That idea arose not only because the sleek V3 resembles today’s stealth aircraft in some ways but also because Reimar Horten claimed in the 1980s, implausibly, that he had wanted to add a layer of charcoal to the V3’s skin to diffuse radar beams; by all accounts, a charcoal coating would not have allowed the craft to evade radar anyway. Though the Horten Ho 229 V3 never saw combat, reincarnations have taken flight in popular culture, such as the propeller-driven, Horten-style flying wing that appears in an airport fight scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark.

The V3 and its ancestral prototypes were taken seriously, though. One of America’s leading aircraft designers, Jack Northrop, showed keen interest in the Horten brothers’ flying-wing glider back in the 1930s and built flying-wing airplanes of his own in the 1940s. For three decades the corporation now known as Northrop Grumman has provided the U.S. military with stealth aircraft, which are essentially shaped like a flying wing.

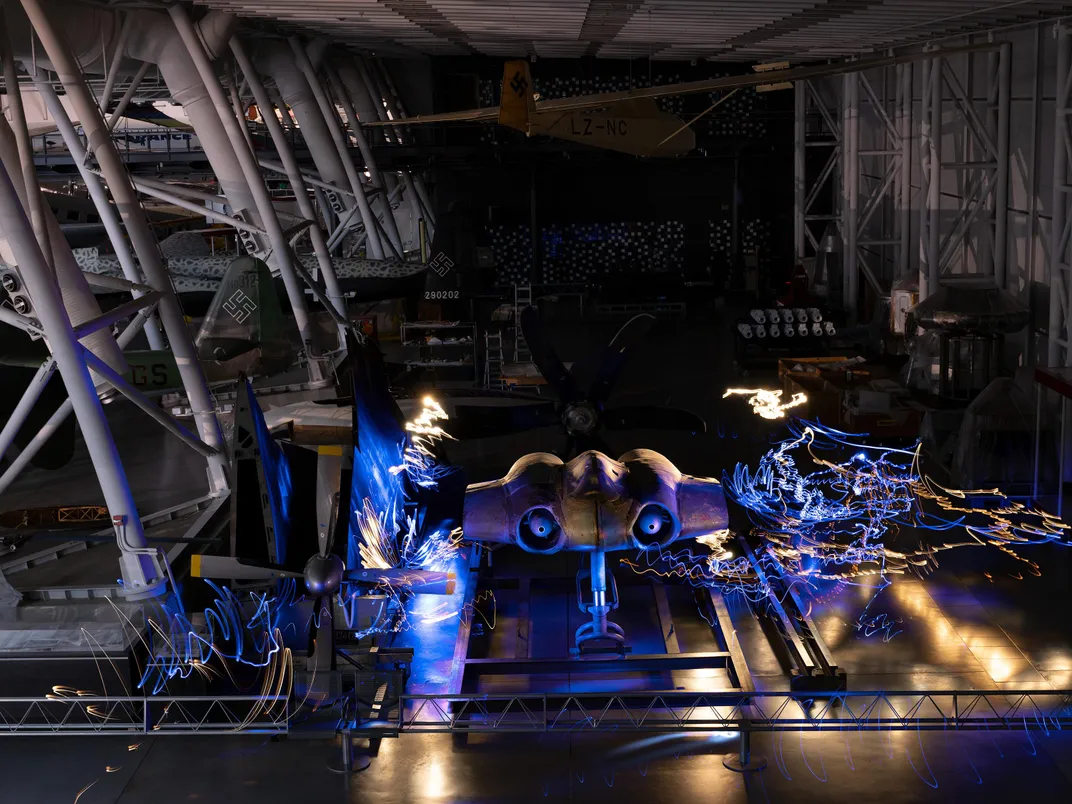

Sometime after the V3 arrived in the States, American engineers studied it closely, according to Russell Lee, a curator at the National Air and Space Museum, who helped restore the aircraft in 2011. “When we took these wooden panels off of the bottom of the center section, we discovered there were burn marks there,” says Lee, “and it suggests that the engines may have been run.” But there’s no evidence this experimental jet, still strangely intriguing after all these years, ever got off the ground.

Click here to see images of Smithsonian curators restoring the aircraft.