Famed for “Immortal” Cells, Henrietta Lacks is Immortalized in Portraiture

Lacks’s cells gave rise to medical miracles, but ethical questions of propriety and ownership continue to swirl

:focal(808x298:809x299)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/53/c3/53c3b6a3-929b-43f1-bf61-2d2cafbbecca/lacks1.jpeg)

In life, Virginia-born Henrietta Lacks did not aspire to international renown—she didn’t have the luxury. The great-great-granddaughter of a slave, Lacks was left motherless at a young age and deposited at her grandpa’s log cabin by a father who felt unfit to raise her. Never a woman of great means, Lacks wound up marrying a cousin she had grown up with and tending to their children—one of whom was developmentally impaired—while he served the 1940s war effort as a Bethlehem steelworker.

After the Axis fell and her husband’s work died down, Lacks delivered three additional children, for a total of five. Sadly, fate denied her the chance to watch them grow. Visiting a hospital with complaints of a “knot” inside her, Lacks received news of a cancerous tumor in her cervix, which had escaped doctors’ notice during the birth of her fifth child. Treating Lacks’s cancer with crude radium implants—standard operating procedure in 1951—doctors were unable to save her life. At the age of 31, the person known as Henrietta Lacks ceased to exist.

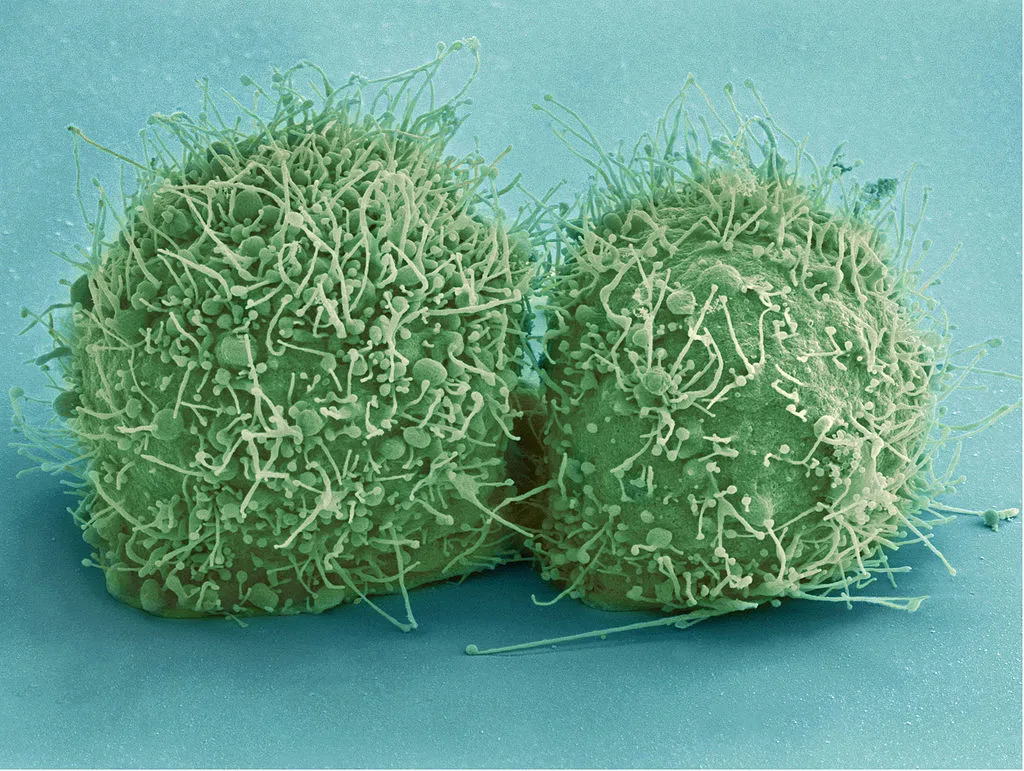

And yet, curiously, a small biological part of Lacks lived on. Tissue samples collected as a part of her radiation treatment proved surprisingly robust in the lab. Doctors were accustomed to tissue samples dying off quickly once removed from their hosts, and were shocked at the unflagging replication rate of the cells from Lacks's cervix.

Physicians recognized the value of Lacks’s tissue samples, but did not feel any ethical obligation to inform her surviving family of their work. As days, weeks, months and years passed, the initial samples continued cell reproduction with no signs of faltering, opening the door to all sorts of previously impossible disease testing. As copies of Lacks’s cells—dubbed “HeLa” cells as a nod to their source—circulated among the global scientific community, paving the way for such breakthroughs as Jonas Salk’s famous polio vaccine, Lacks’s family was never notified. Not only did they not affirmatively consent to the use of Henrietta’s tissue samples for continued research, they didn’t even know about the remarkable properties of HeLa tissue until 1975, when the brother-in-law of a family friend asked offhand about the Lacks cells his National Cancer Institute coworkers had been studying. For more than two decades, the Lacks family had been kept in the dark.

Lacks’s descendants never received compensation and were never asked for input, despite the ongoing worldwide use of Lacks’s cells for biomedical research into diseases running the gamut from HIV to Ebola to Parkinson’s. Her children welcomed the addition of a donated grave marker to her unmarked plot in 2010—“Here lies Henrietta Lacks. Her immortal cells will continue to help mankind forever.”—but the public debate over her exploitation by the scientific community rages on. Her story has been the subject of a widely acclaimed 2010 book and a 2017 HBO feature film produced by and starring Oprah Winfrey.

In the lead-up to the 2017 film, African-American portraitist Kadir Nelson, commissioned by HBO, set out to capture Lacks in a richly colored, larger-than-life oil painting. That visual rendering of the woman whose cells have saved millions was just jointly acquired by the National Museum of African American History of Culture and the National Portrait Gallery, and will be on view on the first floor of the latter through November 4, 2018.

“Nelson wanted to create a portrait that told the story of her life,” says painting and sculpture curator Dorothy Moss. “He was hoping to honor Henrietta Lacks with this portrait, because there was no painted portrait that existed of her.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/46/1a/461ac614-7515-49ed-9c76-35d09d16c77b/henrietta5.jpeg)

In the painting, a kind-eyed, smiling Henrietta looks directly at the viewer, pearls around her neck and a bible held snugly in her overlapped hands. Her canted sun hat resembles a halo, while the geometric “Flower of Life” pattern on the wallpaper behind her suggests both the concept of immortality and the structural complexity of biology. “Nelson captures her strength and her warmth,” Moss says. The artist also signals the darker aspect of Lacks’s story in a subtle way, omitting two of the buttons on her red dress to imply that something precious was stolen from her.

The painting is situated towards the entrance of the Portrait Gallery, in a hall devoted to portraits of influential people. Moss hopes the piece will serve as “a signal to the kinds of history we want to tell. We want to make sure that people who have not been written into traditional narratives of history are visible immediately when our visitors enter.”

Moss is hopeful that the new addition to the gallery will both celebrate a courageous and kind-hearted woman and get people talking about the nuances of her story. “It will spark a conversation,” Moss says, “about people who have made a significant impact on science yet have been left out of history.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)