The Fantastic Beasts of John James Audubon’s Little-Known Book on Mammals

The American naturalist spent the last years of his life cataloguing America’s four-legged creatures

The spring of 1843 came late. In March the Ohio and Mississippi rivers were still choked with ice. But by April 25, the weather had turned fine in St. Louis, where the steamboat Omega stood alongside the wharf, its bow pointed upriver. Onshore, Omega’s captain rounded up the last of 100 fur traders who’d been out all night and herded them aboard. Half were hung over, the other half still drunk. Looking on with amusement from the deck was white-haired John James Audubon, one day shy of 58. As Omega swung into the current, Audubon studied the dark waters of the Mississippi, on which he had voyaged so far and so many times before.

Audubon was the most famous naturalist painter in America. His masterwork, The Birds of America, had been completed five years earlier. Audubon honed his technique and made many of his bird drawings during nearly two decades on the frontier, mostly in river towns from Louisville to New Orleans. The Birds of America earned Audubon a small fortune. He built a house on the Hudson River, in what is now the Upper West Side of New York City, where he might have lived out his days at ease.

Yet he didn’t.

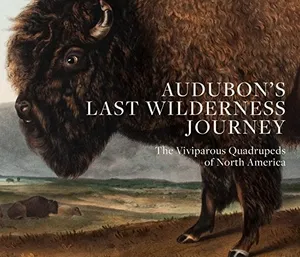

Even before completing his bird book, Audubon began thinking about documenting mammals in the same fashion. His collaborator, John Bachman, a clergyman and amateur naturalist from Charleston, would provide a text based on Audubon’s report from an expedition into the West. The new work was to be called The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America. A later edition dropped the clunky reference to gestation and was titled The Quadrupeds of North America. This month, a new edition of the work is being released by Giles publishers and Auburn University.

Audubon, carrying a letter of introduction from President John Tyler, left New York in early March 1843, hoping that he might reach “the base of the Rocky Mountains.” Accompanied by four assistants, Audubon ascended the Missouri River, traveling through a stark land alive with game. “The hills themselves which gradually ascend to plains of immense extent, are one and all of the very poorest description, so much so that one can scarcely conceive of how millions of buffaloes, antelopes, deer, etc. manage to subsist,” he wrote on May 24 to a friend back East, “and yet they do so, and grow fat between this and autumn.”

The party stopped well short of the Rockies, at Fort Union, in the western Dakota Territory, where Omega arrived on June 12. Along the way they observed rabbits, squirrels, gophers, mule deer, and a couple of species of wolves, one of which, the prairie wolf, is the animal we know as the coyote. Audubon also discovered a few new species of birds, and encountered Indians whose numbers had been ravaged by smallpox. He found their living conditions wretched.

Audubon's Last Wilderness Journey: The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America

This entire work is a remarkable record highlighting the wider importance of the North American wilderness and the beauty of Audubon’s detailed illustrations.

During the two months Audubon spent at Fort Union he became withdrawn. He lost interest in hunting, a passion that had made all of his work possible. The slaughter of buffalo by white hunters, who took the hides and left the carcasses to rot, appalled him. “Daily we see so many that we hardly notice them more than the cattle in our pastures about our homes,” Audubon wrote in his journal. “But this cannot last; even now there is a perceptible difference in the size of the herds, and before many years the Buffalo, like the Great Auk, will have disappeared; surely this should not be permitted.” Audubon returned to New York in November of that year.

Bachman would later complain that Audubon’s journals contained little of value—the artist had learned less about the mammals of the region than had Lewis and Clark four decades earlier. Audubon, he said, should have pressed on beyond the well-known area around Fort Union.

Audubon had a knack for depicting bird plumage, down to the tiniest wisp of a barbule, and now he would apply his gift to mammals, capturing the warmth and softness of fur and hair. His painting of a wildcat, or bobcat, was based on a live animal that had been captured, possibly in South Carolina, caged, and shipped to the artist at his studio in New York. This particular image is from an edition of Quadrupeds on loan from the Audubon Society to the Smithsonian Libraries.

But Audubon’s eyesight soon faltered and he started drinking heavily. In 1846, he stopped working and began a slide into dementia. On a visit in 1848, Bachman was shocked to find that while his friend still looked like himself, “his noble mind is all in ruins.” Audubon died on January 27, 1851.

The Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America, sold by subscription, was published in installments between 1845 and 1848. When Audubon became incapable of continuing the project, his son John Woodhouse Audubon took over, producing about half the 150 plates. A few of the son’s images were worthy of the name Audubon, but most were awkward imitations of his father’s style, poorly proportioned and lifeless. Like the journey on which it was based, the Quadrupeds is an imperfect thing that fell short of its goal, an incomplete but beautiful farewell from an American master.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/HS4RET.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/HS4RET.jpg)