The Farmworker’s Champion Dolores Huerta Receives Her Due, Even as the Struggle for Justice Continues

We must continue the struggle against present-day agricultural production and labor practices, says the director of the Smithsonian’s Latino Center

In the lyrics of his song, “La Peregrinación,” or The Pilgrimage, the acclaimed Chicano musician and composer Agustín Lira captures a pivotal moment in this country’s labor history—the 1965 Delano Grape strike and the subsequent 1966 farm workers’ march in California.

“From Delano I go to Sacramento/ To Sacramento to fight for my rights,” Lira wrote, breathing lyrical voice into his life as a community activist and former farmworker.

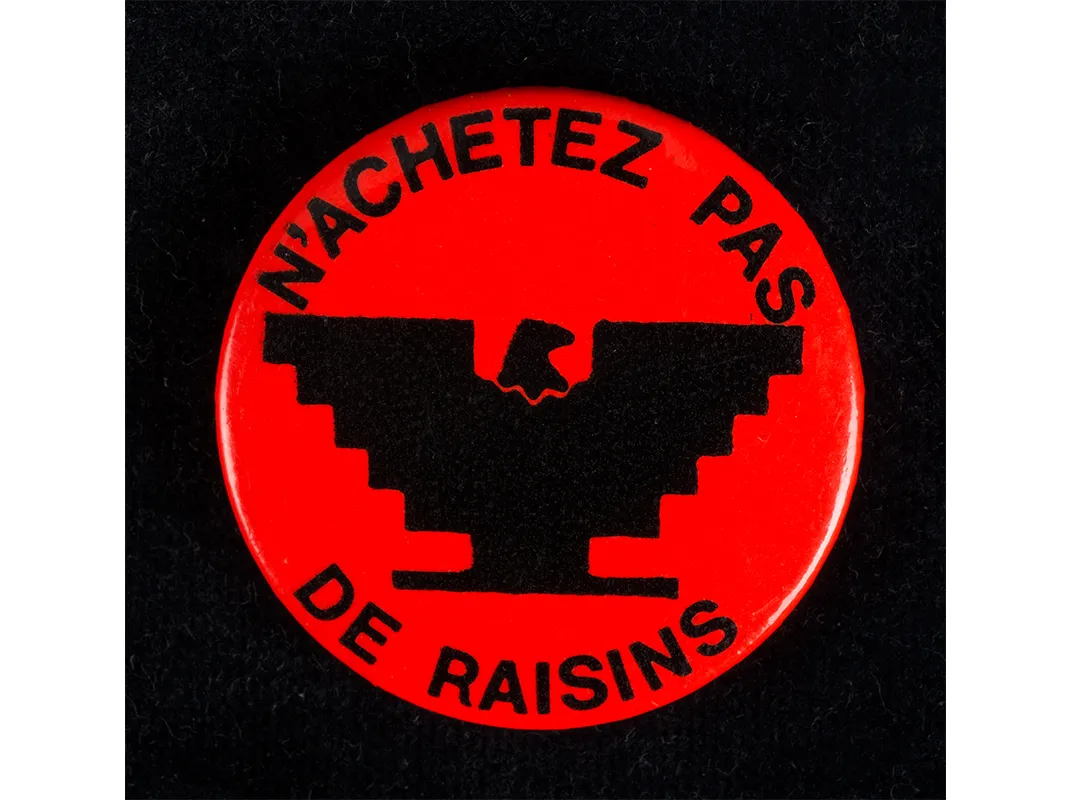

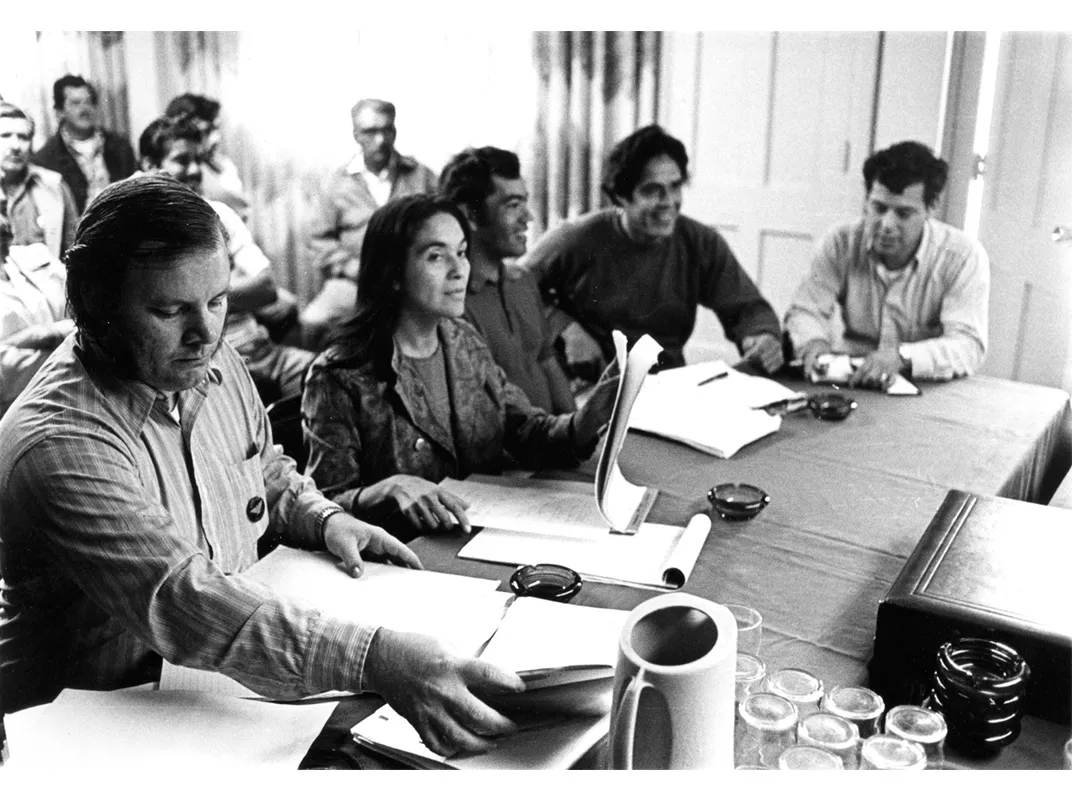

Spearheaded by Mexican American and Filipino field laborers whose leaders had joined to form what would soon become the United Farm Workers (UFW), the effort forced major grape growers to sign landmark contracts with the UFW.

Lira, a National Endowment for the Arts National Heritage Fellow, mobilized farmworkers into action:

And what should I say?

That I am tired?

That the road is long and the end is nowhere in sight?

I did not come to sing because I have such a good voice.

Nor do I come to cry about my bad fortune.

Today, the singer/songwriter continues to chronicle the experiences and little known histories of Chicano, indigenous and immigrant communities integral to California’s cultural fabric. His headliner performance this summer at the Smithsonian’s annual Folklife Festival—accompanied by his own group, Alma, and the Los Angeles-based Viento Callejero, an urban-style tropical music ensemble—was a wild success.

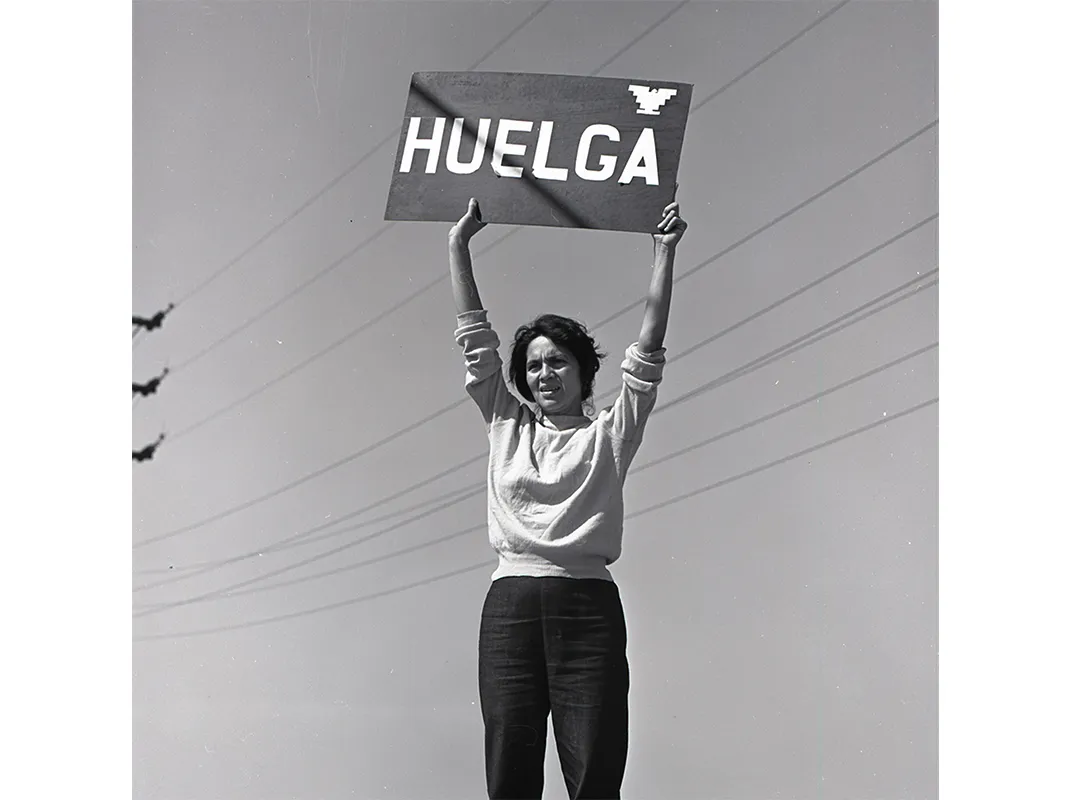

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the farmworkers movement, when the San Joaquín Valley of Central California became ground zero in the struggle against exploitation and oppression. There in the fertile fields, the prodigious table grape crop became the symbol of the workers’ struggle, when grape-pickers from the Delano area refused to collect the ripening fruit to protest their poor wages and abysmal living conditions. The strike lasted five years, fueled by wide national and international support from consumers, students, activists, unions, religious institutions and other public sector entities. (As a product of the Chicano Movement, I spent many hours in picket lines during the grape and subsequent lettuce boycotts.)

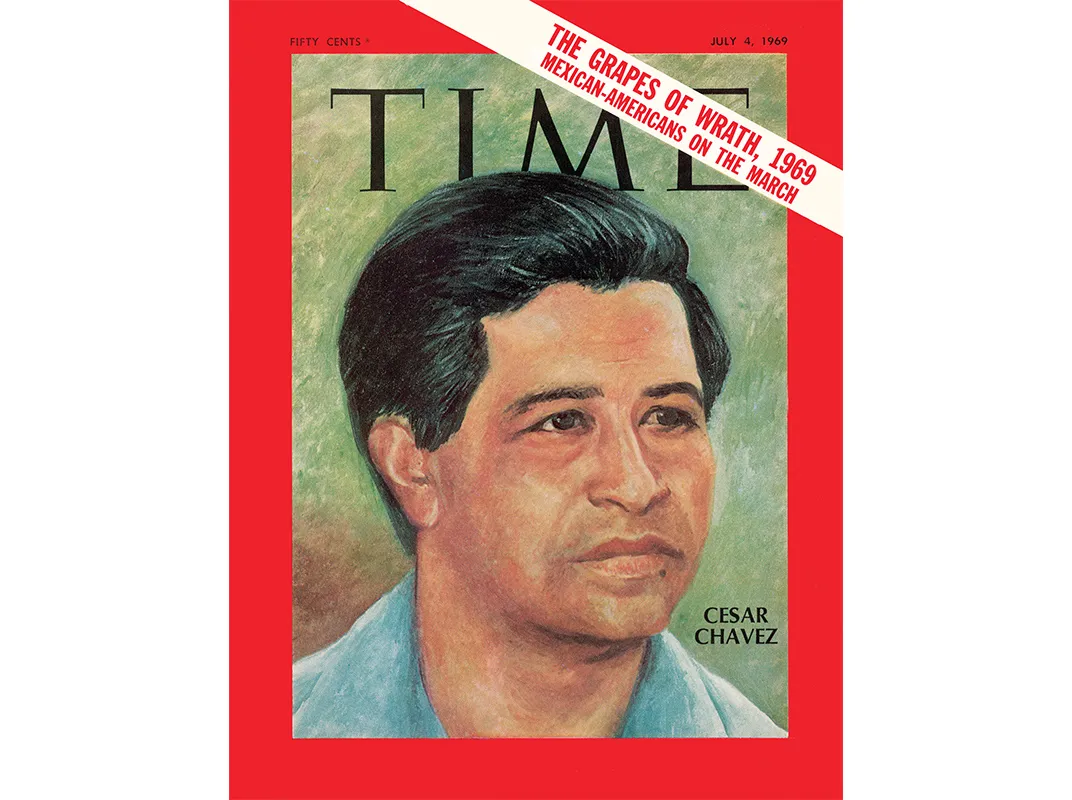

It is important to appreciate the multicultural nature of the farmworkers movement. The United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC)—which later became the UFW—emerged in 1966 from the consolidation of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee, led by Filipinos Larry Itliong, Philip Vera Cruz and Pete Velasco, and César Chávez’s National Farm Workers Association. The merged union later affiliated with the AFL-CIO.

Unfortunately, the role of the Manongs (Filipino term of respect for an older man) in forging the farmworkers movement is not well documented, despite the fact that it was 1,500 Filipino farmworkers who first walked off their jobs and actually launched the strike. The UFW, under the leadership of Chávez, tended to overshadow—one can argue, unintentionally—the Filipinos’ role, as well as the participation of other ethnic farmworkers. The half-hour documentary Delano Manongs: Forgotten Heroes of the United Farm Workers, made by Marissa Aroy and Niall McKay in 2014, has recently been screened across the country and is bringing new light to their important role.

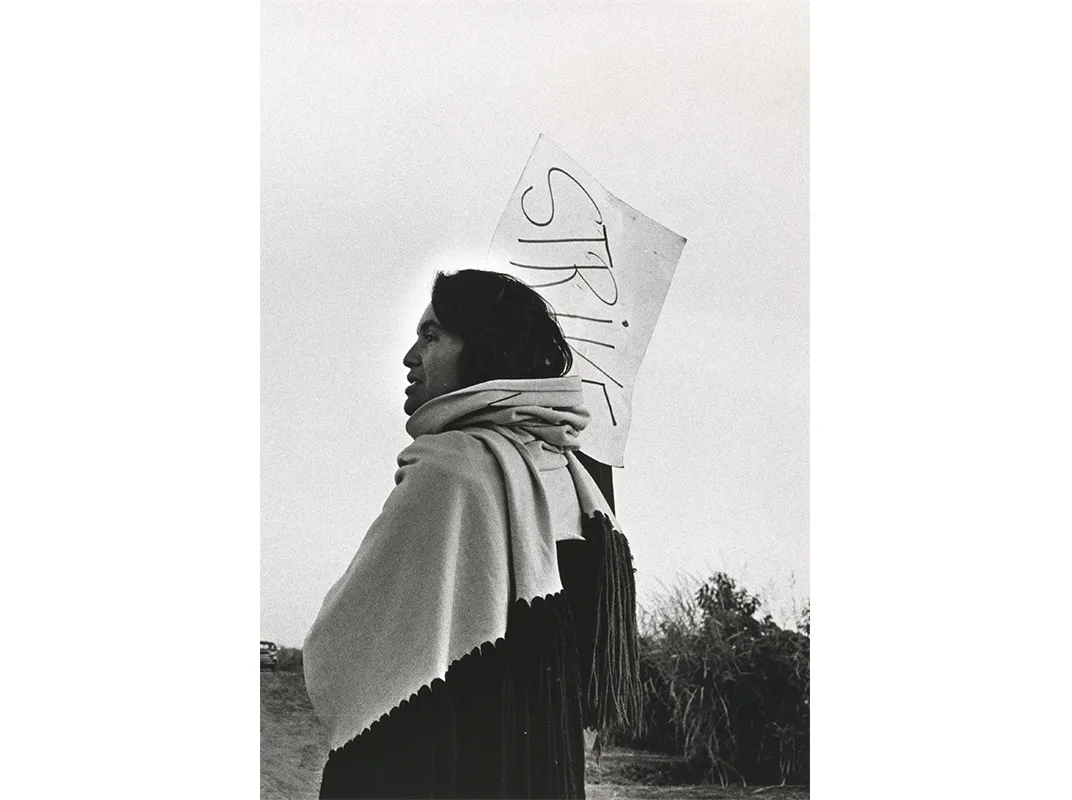

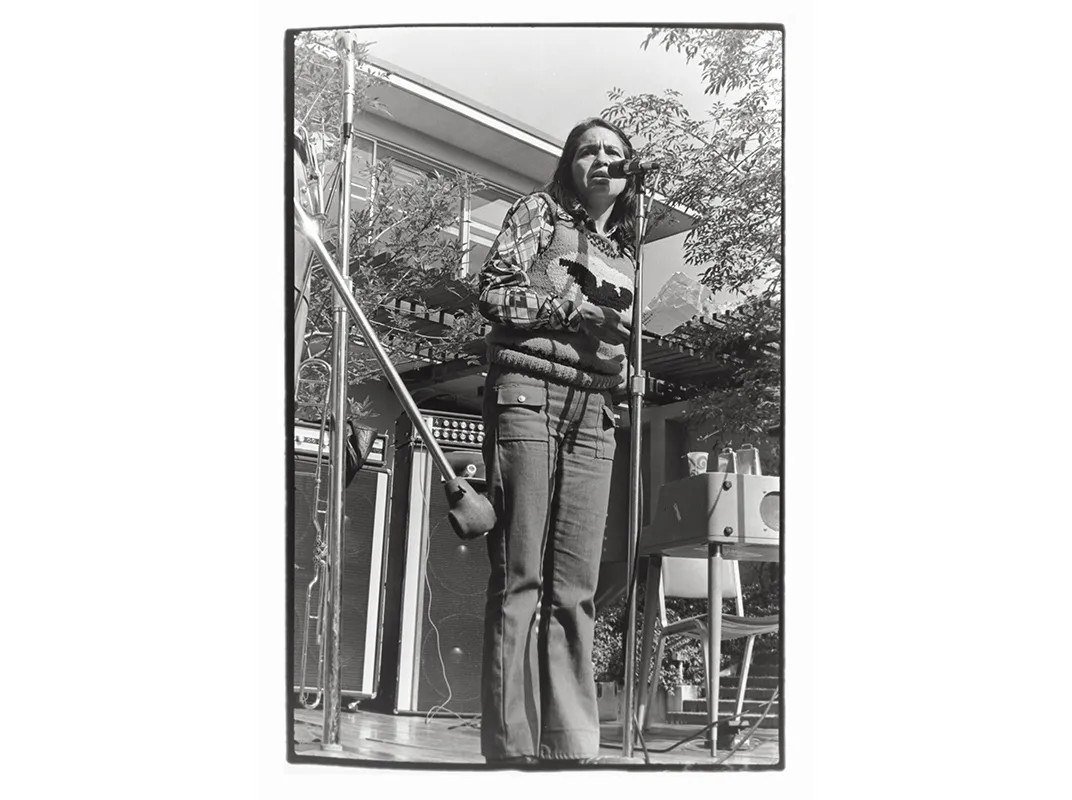

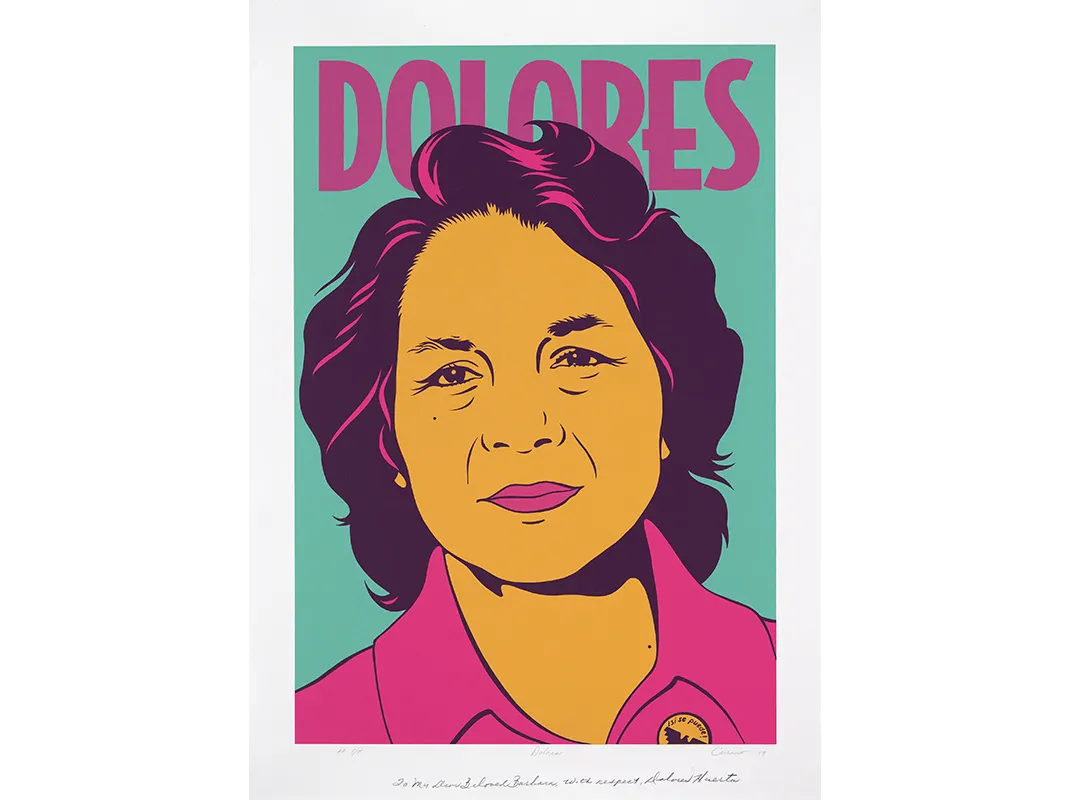

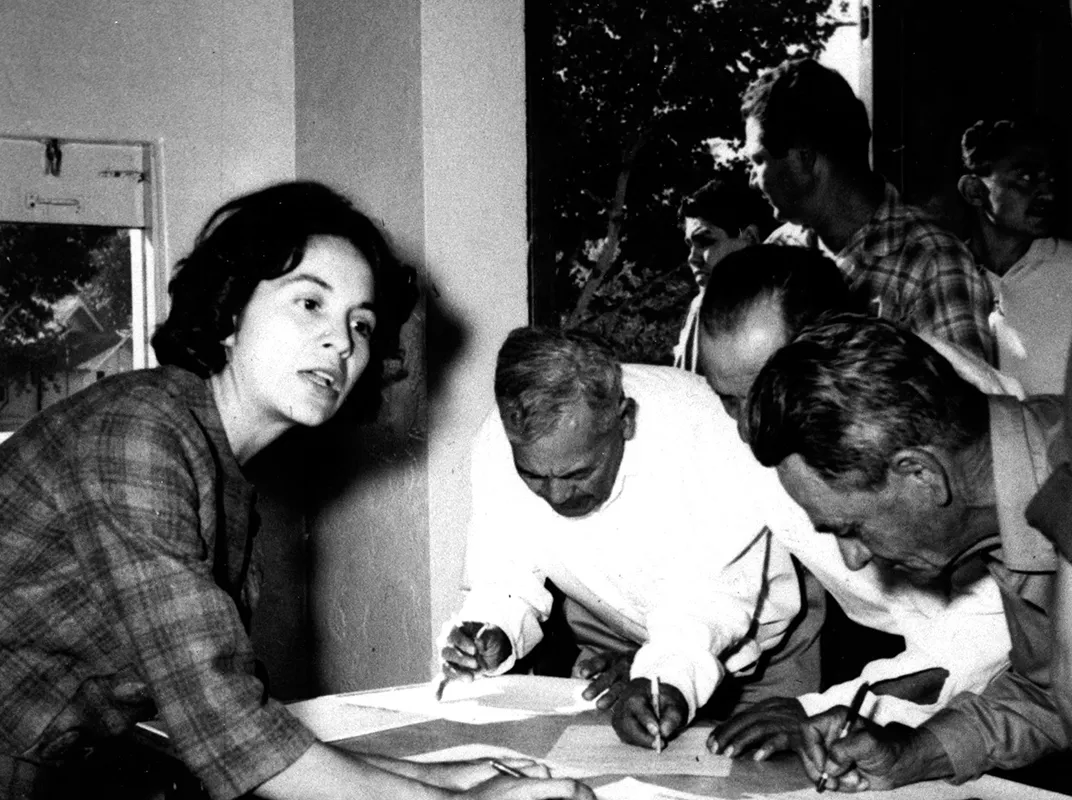

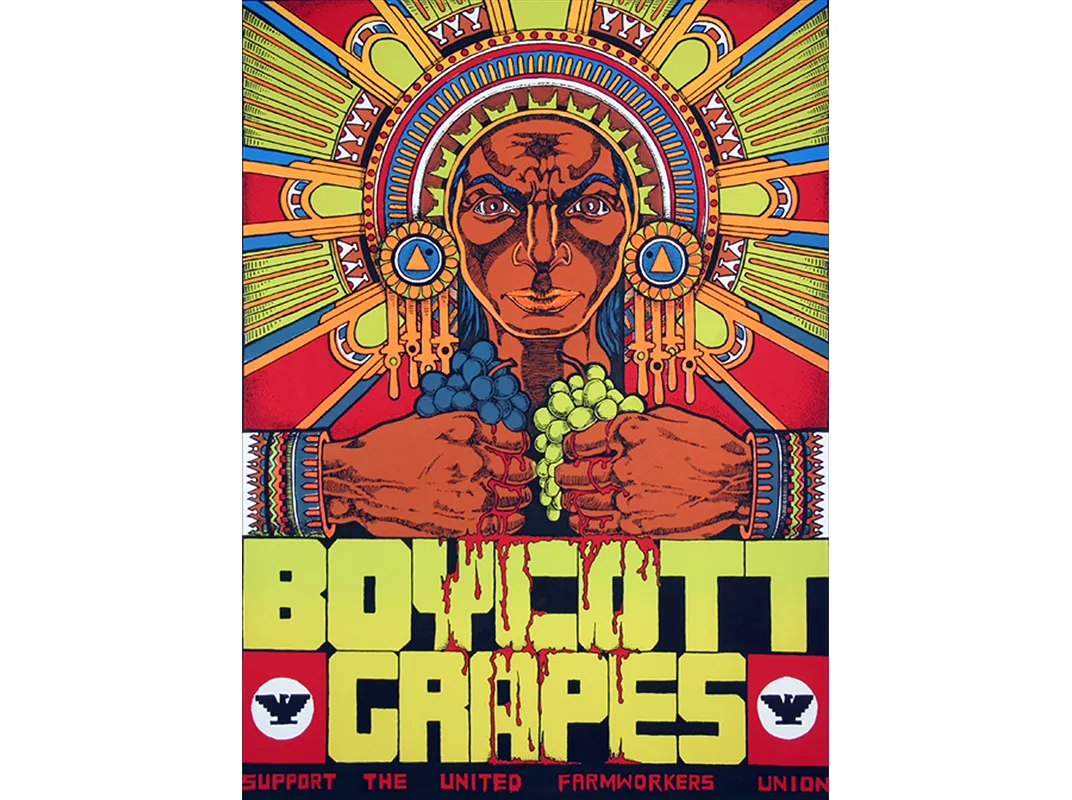

Playing a tactical counterpart to the charismatic César Chávez, Dolores Huerta, a fearless, persuasive and pragmatic woman, marched to Sacramento in 1966 with the farm workers. (The pair had cofounded the National Farm Workers Association in 1962.) This summer, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery cemented her legacy with the opening of the exhibition, One Life: Dolores Huerta, highlighting the decisive role Huerta played in the farmworkers movement. Organized by Taína Caragol, the museum’s curator of Latino art and history, the show features photographs, original speeches, UFW ephemera and Chicano art.

“Dolores Huerta has not gotten her due for the pivotal role she played in the farmworker movement, especially when compared to César Chávez’s notoriety,” notes Caragol. “Featuring her as part of the Portrait Gallery’s One Life series allows us to shed light on the life and accomplishments of this extraordinary American,” she says.

Huerta realized her vision of a better day for farmworkers, leaving her distinct fingerprints on each major UFW victory. Throughout her career, Huerta, mother of 11 children and now 85, continuously embodied new models of womanhood, inspiring generations of women activists.

With the coupling of the Agustín Lira and Alma concert and the opening of the Dolores Huerta exhibition, Smithsonian audiences are being introduced to this important chapter in U.S. labor history with a celebration of two of its notable leaders.

At the same time, these programs serve to remind us that the struggle is not over.

Today’s farmworkers, still mostly composed of Mexican Americans and Mexican immigrants, compose 60 percent of all farm labor in this country and are subject to challenging working and living conditions. Despite previous labor victories, they are still under-employed, underpaid and poorly educated—only 28 percent have the equivalent of a high school education and seasonal workers average just $9.13 per hour.

According to the Wilson Center’s Migration Policy Institute, demand for labor-intensive fruits, nuts, vegetables, flowers and other horticultural specialties will continue to rise, thus further impacting the lives of these workers for the foreseeable future. Currently, the estimated value of these commodities exceeds $50 billion annually.

The Institute’s 2013 study, Ripe with Change: Evolving Farm Labor Markets in the United States, Mexico, and Central America, notes that while many workers would like to move up the agricultural job ladder, “the job pyramid in agriculture is steep, offering relatively few opportunities for those who begin as seasonal workers to move up to year-round jobs in agriculture or to become farm operators.” The situation is exacerbated by the workers’ limited access to capital in these capital-intensive agricultural sectors, an impediment to becoming operators themselves.

And, the situation is further complicated by the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeal’s recent decision to deny the Department of Justice’s request to stay the temporary injunction of implementation of the expanded Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), which included the Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA).

Nearly 50 percent of all farmworkers are foreign born, mostly Mexican and Central American. Farmworker Justice, a Washington, D.C.-based advocacy group, estimates that 700,000 farmworkers and their spouses could be eligible to come forward to apply for temporary protection from deportation and work authorization under these deferred action opportunities. The uncertainties around the future of President Obama’s executive action, issued last November, further cloud the future of these workers and the operations of farm operators, not inconsequential when you consider the financial impacts and human factors hanging in the balance.

Americans depend on the hard work and sacrifices of farmworkers and their families for large portions of our food supply. Farmworkers work grueling days. Their tasks are tedious and backbreaking. Their pay has them at or teetering at poverty levels. Agricultural employers are exempted from some key employment law protections, and current enforcement levels are less than desirous, leading to widespread violations in some sectors.

While we acknowledge and celebrate the accomplishments of the past, we would do well ethically to maintain a high level of awareness of present-day agricultural production and labor practices, understanding that the continuing struggle of farmworkers and our own sustenance are intricately connected. Let conscience be our guide.

La Marcha no ha terminado. The march is not over.

The exhibition “One Life: Dolores Huerta” at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. is now closed. The documentary Delano Manongs: Forgotten Heroes of the United Farm Workers is available on DVD and BluRay. The music of Agustín Lira is available through Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Diaz-Eduardo-11925.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/73/66/736646c0-67c9-4d3f-9b32-c9bc96872c4c/dh-at-founding-convention_exhdh04-web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/0b/fe/0bfe29e6-d3a8-4ad5-87b4-a93ad6e61ef1/exhdh16-web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b1/b0/b1b0ccb5-5bfa-4423-af11-58ac2ba9e7a5/lone-man-in-field_exhee1666-web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/2f/cb2fa63d-2bc8-4e60-9d70-ad4f02ca769f/gallo-negotiations_exhdh38-web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7d/9c/7d9c4b9b-e9eb-4b38-a9f4-3b5e24417914/dh-speaking-to-a-group-of-women_exhdh35-web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/cb/a7/cba7ec1b-962f-4b2d-ac12-74af3c5721fb/dh-marching-california_exhdh13-web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Diaz-Eduardo-11925.jpg)