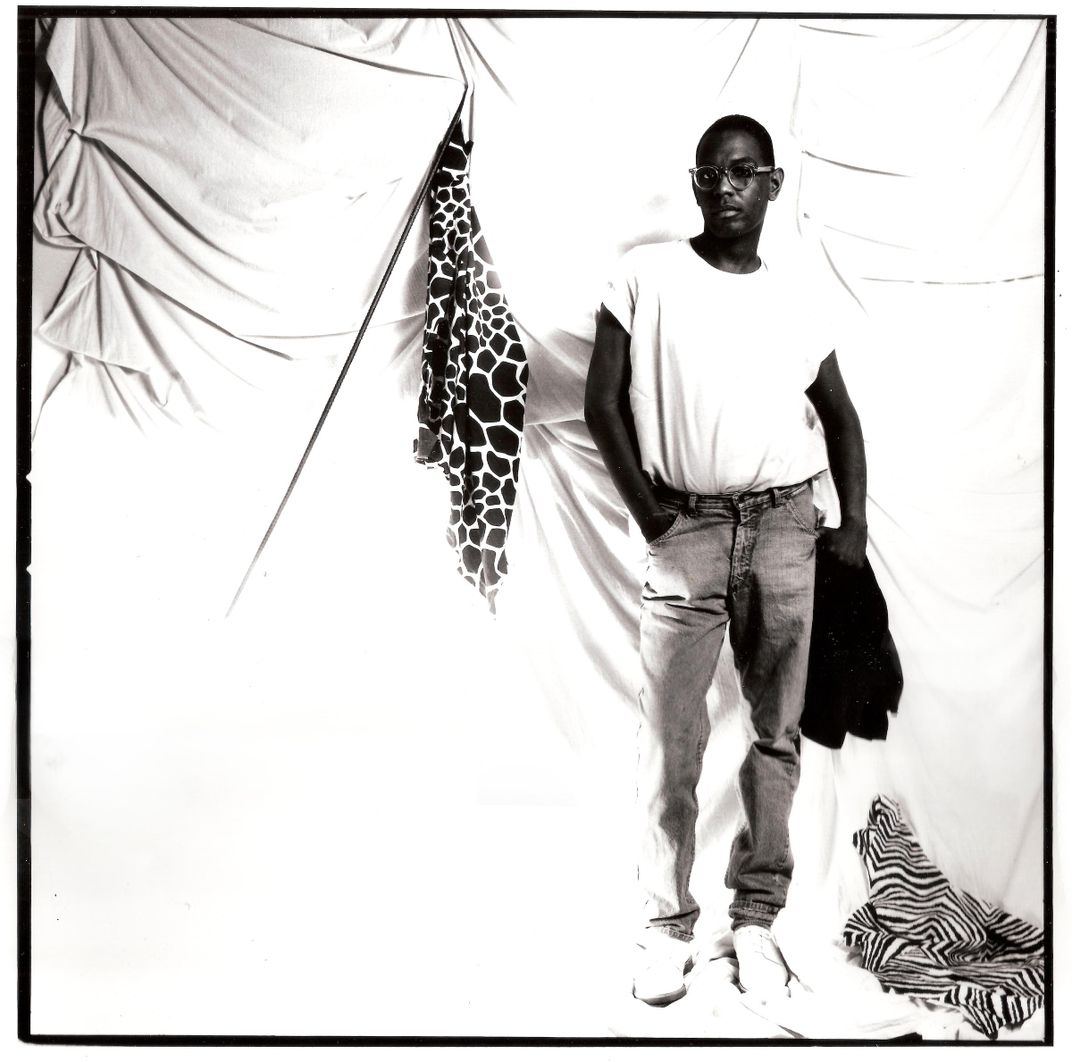

The fashion designer Willi Smith grew up working class in the 1950s in a family where, he once said, “there were more clothes in the house than food.” His father was an ironworker; his grandmother cleaned houses for a living. His mother and grandmother sewed their own clothes. Decades later, when Smith was nominated for a fashion award, he remembered, “My mother and grandmother were always ladies of style and still are. I guess they taught me that you didn’t have to be rich to look good.”

Making clothes that anyone could afford to look good in turned out to be the force that powered Smith’s career. Now, with the exhibition “Willi Smith: Street Couture,” the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York City, is looking back on the work of one of the country’s most successful Black fashion designers.

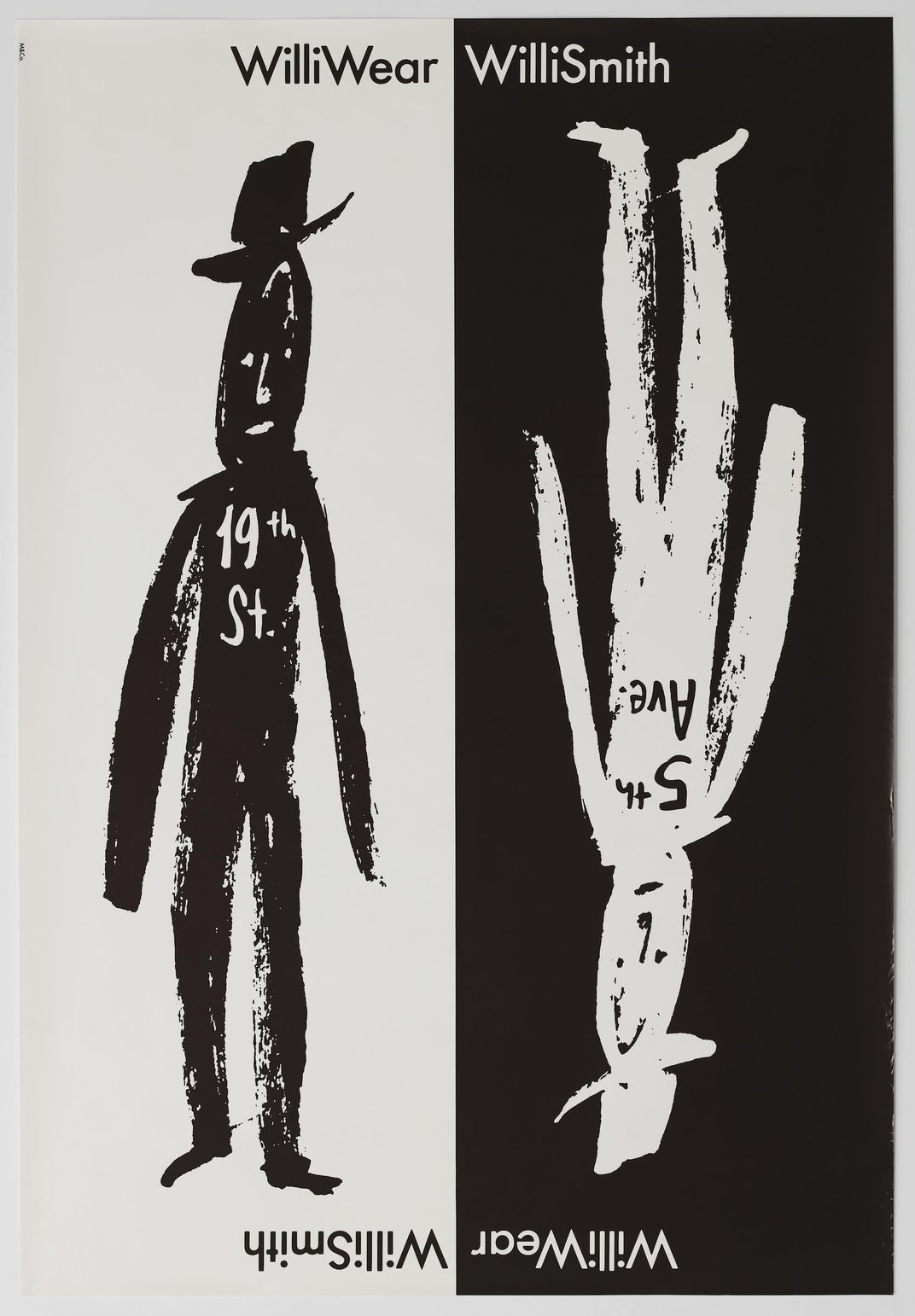

Smith, who died in 1987 at age 39, was a rising star in fashion in the mid-1970s when with a partner he founded his own company, WilliWear. With a mission of combining high-end design with mass-market production, WilliWear made clothes priced and sized for everyday people.

At the time, other designers, at all price points, tended to focus on one particular slice of the fashion market, says Alexandra Cunningham Cameron, the museum’s curator of contemporary design, who organized the exhibition. Smith, she says, was different: He was “interested in a clientele of diverse body types, who had diverse bank accounts, who were up all night or who had a career and were in the office all day,” she says. “He was interested in people who lived in the city, he was interested in people who lived in the suburbs. He was very cagey about not saying specifically who he was designing for, because he was designing for everyone.”

The exhibition opened in March 2020 for a single day, before New York’s museums were ordered shut because of Covid-19. Now Cooper Hewitt is reemerging after its 15-month pandemic-induced closure.

For the museum’s reopening day, June 10, masses of blossoms spilled from the building’s sweeping entry staircase onto the sidewalk, in a temporary installation by Lewis Miller Design, which has created flower flashes like it in New York and elsewhere. Now through October 31, there’s no charge for admission at Cooper Hewitt. It’s the longest period the museum has been open for free since it moved into the Carnegie Mansion as part of the Smithsonian in 1976. The Immersion Room, museum shop and Arthur Ross Terrace and Garden will reopen July 1; the café will remain closed. But with Covid-19 restrictions limiting the museum to only 25 percent capacity, the mansion feels roomy enough for Andrew Carnegie himself.

Born in 1938, Willi Smith grew up in Philadelphia and studied commercial art in high school. He got his first break into fashion through his grandmother, who cleaned house for someone who had a connection to the luxury designer Arnold Scaasi in New York. Smith apprenticed with Scaasi while still a teenager, learning about the business of designing expensive dresses for society women and movie stars—or what Smith later called the “clothes I didn’t want to make.” He was admitted to Parsons School of Design in 1965, but expelled two years later, reportedly because he openly had a relationship with another man.

He found success designing for sportswear businesses and was nominated twice for a Coty Award, then a top honor in American fashion. In 1976, he and his former assistant Laurie Mallet founded WilliWear; she handled the business side and he the design. WilliWear was a hit. Its affordable, wearable clothes were picked up by Macy’s, Bloomingdale’s and eventually hundreds of stores. After 11 years, the company had reached $25 million in annual revenue when Smith died, from complications of AIDS.

The clothing on display at Cooper Hewitt has recognizable, simple shapes: a pair of striped cotton shorts, a voluminous tweed coat, a belted tunic. He hoped his customers would combine them with items from thrift shops or their closets—anything to make it their own. Cunningham Cameron acknowledges that the “garments themselves may not be extraordinary,” and says that Smith called his own designs “background clothes” because, he said, he wanted to “let the person come through.”

“He was an activist in a way that other designers of the time were not,” she says. “I think he was interested in fashion as a tool of equity.” Keeping prices accessible was only one aspect of his social project. WilliWear’s signature pants had a wraparound waist, so they could fit bodies of many shapes. He created patterns for Butterick and McCall’s, so people could sew their own versions of his clothes at home. And while gender fluidity may be increasingly common in fashion today, WilliWear was the first to show womenswear and menswear on the same runway, with female and male models wearing pieces from each line.

Through it all, instead of issuing top-down fashion edicts, he reveled in a kind of back-and-forth with his clientele: “My customers put things together that amaze even me,” he once said. “But I learn from them. First I give them ideas and then they give me ideas.” Long before streetwear became the potent influence it is in fashion today, Smith found inspiration in the streets.

At the same time that he was designing clothes for a wide swath of America, Smith was mingling and collaborating with some of the most experimental artists in New York. Cunningham Cameron points out that many of them were avant-garde artists who shared some of his values “in thinking about the street as a site of innovation” or encouraging people to “look at common objects in the world in a new way.”

Smith designed the costumes for “Secret Pastures,” a 1984 work by the dance pioneers Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane; Keith Haring created the sets. Nam June Paik and Les Levine, two of the first artists to use video as an art form, both did work for WilliWear projects.

Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer and other visual artists designed T-shirts for a division of WilliWear called WilliWear Productions. Today, mass-produced T-shirts designed by artists are common in fashion, but Cunningham Cameron says these were the first.

After he achieved financial success with WilliWear, Smith remained connected to the downtown creative world. In the exhibition catalogue, Kim Hastreiter, cofounder of Paper magazine, remembers Smith moving into her building in what was then the grimy neighborhood of Tribeca, to live surrounded by artists; Smith’s limo waited outside on their “rat-infested street” to take him to work.

This and other stories are strewn through the Willi Smith Digital Community Archive, an online extension of the exhibition filled with essays, images and reminiscences. Even pre-pandemic, the archive was intended as a key part of the show. One reason was practical: When Cunningham Cameron and her colleagues went looking for examples of WilliWear to display, people told them, “ ‘Oh, I wore it out,’ ” she says. “We were simultaneously elated and devastated to hear this over and over again, because it was an indication of how much people loved the clothing, but also we had no examples of the clothing!” So the archive has been a way to gather new images and sources since the show opened briefly last spring.

And because documentation of this seminal Black designer is limited, she says, “We wanted a way to share the experience of the discovery, of hearing the stories of all the people in Smith’s world, or worlds—artists, dancers, customers, WilliWear employees, filmmakers, models” and to make them available anywhere. She and her colleagues are now plotting to add more: a virtual exhibition platform, still in the works, would let visitors dig deeper and would make more of the show available to anyone who can’t see it in New York.

Now, after 15 months of quiet, Cooper Hewitt is bustling again. Through Black Lives Matter protests, Covid-19 and economic upheaval, the Smith exhibition stayed in place, ready to tell the story of an under-recognized Black designer who died in another lethal pandemic. Cunningham Cameron hopes it might reach a new audience today. People “who have not questioned the history they’ve been taught have not been able to hide from the fact in the last year that they should be critically thinking about their way of seeing the world,” she says. “And if that experience encourages someone new to come to see this exhibition, then I think that would make us all very happy.”

“Willi Smith: Street Couture” is on view at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, 2 East 91st Street, New York, New York, through October 24. Visitors must acquire timed-entry tickets in advance.

Also on view:

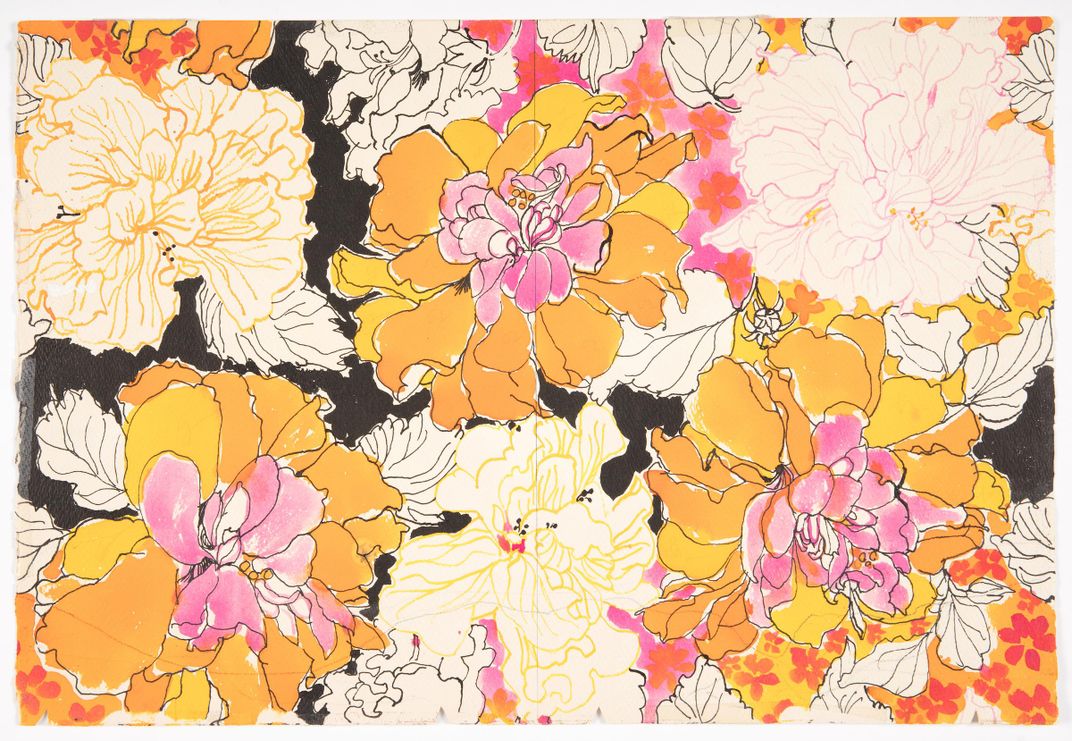

“Suzie Zuzek for Lilly Pulitzer: The Prints That Made the Fashion Brand” (through Jan. 2, 2022) shines a spotlight on the Key West textile designer who created the distinctive floral- and animal-printed fabrics that helped turn Pulitzer’s clothes into preppy perennials. Painted in watercolors, screen-printed in pulsating hues or sewn into Pulitzer’s simple shift dresses, they bring the Florida heat to Fifth Avenue.

“Nature By Design” includes selections from Cooper Hewitt’s collection of objects and patterns drawn from nature: a toast rack by the Scottish designer Christopher Dresser, who trained as a botanist; a room dedicated to dyes made from the cochineal insect; a garden’s worth of painted ceramics; and vases designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany, who said, “Nature is always right—that is a saying we often hear from the past; and here is another: Nature is always beautiful.” Nearby is a small show on modernist gardens by the French brothers André and Paul Vera (both exhibitions through Jan. 2, 2002).

“Jon Gray of Ghetto Gastro Selects,” opening July 1, is the latest installment in a series that invites designers and others from outside the museum to curate objects from Cooper Hewitt’s collection. Gray is a founder of the Bronx-based chefs’ collective and advocacy group Ghetto Gastro (through Feb. 13, 2022).

“Contemporary Muslim Fashions” (closing July 11) looks at trends in modest Muslim dress around the globe, including dozens of gorgeous shimmery brocade, silk and satin gowns from Indonesia, Malaysia, the Middle East and Europe, and also hip hop-inspired contemporary sportswear.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f0/6c/f06c717b-01c6-4123-809e-67c2be3d6c7c/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/63/12/6312daa0-65ad-47b4-8b32-daccfbe56f26/social-media-dimensions.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SusannahGardiner.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/SusannahGardiner.JPG)