A Look at the Struggles and Celebrations of LGBTQ Americans

Artifacts from the National Museum of American History highlight the broader story of gay history and activism

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/38/d5/38d5326a-01cd-49e4-8c97-d39339e6bb6d/gay-is-good.jpg)

For many years, whenever someone asked Smithsonian curator Katherine Ott what was on her artifact wish list, she’d reply: “John Waters’ mustache.”

It was partially a joke, but Ott had long been determined to snag some piece of memorabilia tied to the legendary director, known for his subversive cult films and distinctive facial hair. “Waters is irreverent and creative and has inspired many kinds of artists,” she says. “He’s a cultural force for people who are different.” So, when a research fellow joined Ott’s department and mentioned she’d once invited Waters to speak at her university, Ott jumped at the opportunity to connect. Before long, Ott was on the phone with Waters himself, and Ott got her wish—more or less.

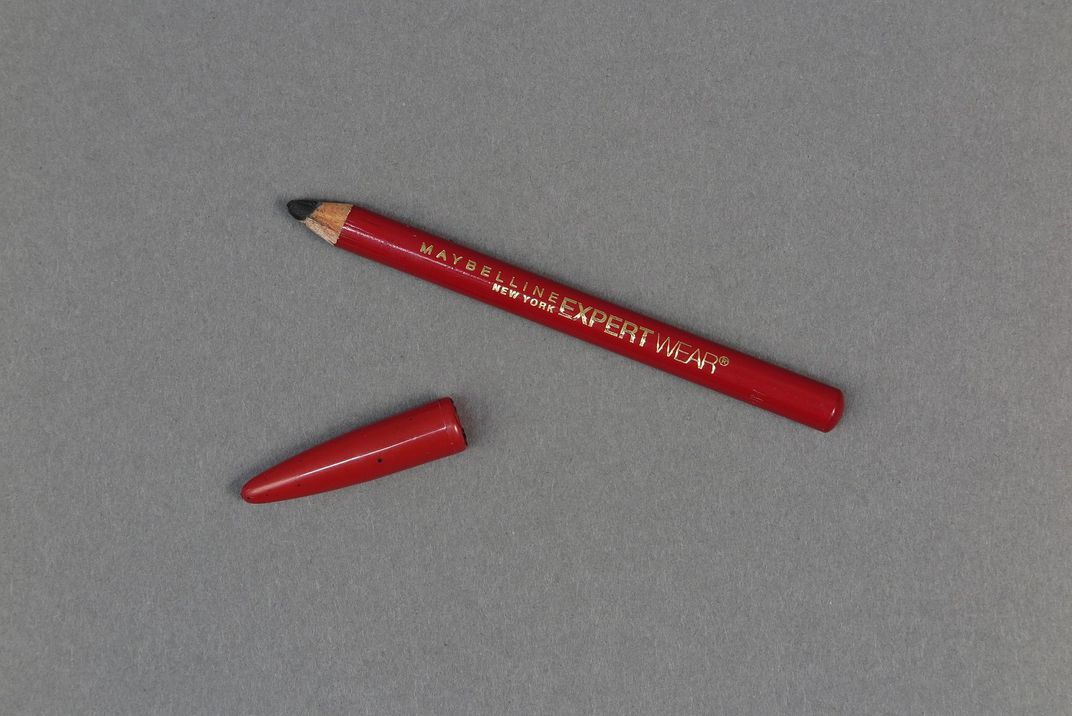

Though Waters’ mustache stayed firmly planted, the filmmaker sent over a Maybelline eyeliner pencil like the ones he used to fill in his stache, plus a jar of his well-documented favorite lotion, La Mer (emptied of its pricey contents).

"Illegal to be You: Gay History Beyond Stonewall," a case exhibit, that debuted June 21, 2019 through July 6, 2021, at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C. highlights Waters’ artifacts and dozens of other items that showcase different aspects of gay history in the United States, in honor of the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots.

The display case marks half a century after patrons of the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in New York City, rioted in response to a police raid.

Though the exhibit uses the anniversary as an entry point, the organizers intended to highlight the broader context of gay history and activism, and the “everyday experience of being queer,” Ott says—for celebrities like Waters and for the millions of other less-famous gay Americans. After all, Stonewall, important as it was, is only one piece of the long history of LGBTQ people in the U.S., she says.

“Stonewall itself, in my view, was unique and important, but within a small context. It was not the birth of the modern gay rights movement, although that's been repeated over and over,” Ott says. “It has this outsize reputation. We wanted to kind of counter that, and draw attention to how long of a history gay activism and gay life has had.”

In many ways, that history has been rife with struggle, as some of the display’s artifacts illustrate. Among them are lobotomy knives that were used as late as the 1970s, when homosexuality was still considered a psychiatric disorder, to “cure” gayness by disconnecting the brain’s frontal lobes to make patients more docile; buttons and stickers plastered with Nazi symbols and violent slogans; and equipment from the lab of Jay Levy, who researched a cure for HIV/AIDS when the virus tore through the LGBTQ community in the 1980s.

Some of the exhibit’s most powerful objects once belonged to Matthew Shepard, a young gay man whose 1998 murder became a defining moment in the gay rights movement and inspired a push to expand hate crime protections. When Shepard’s remains were interred at the Washington National Cathedral last year, his family donated a superhero cape from his childhood, as well as a wedding ring he’d bought in college but never got to use before he was killed at age 21.

The team working to bring the display case together thought it essential to portray the element of risk for LGBTQ people in this country. Being gay, or really “any sort of different,” still often means experiencing discomfort and even danger, Ott says.

“The people at Stonewall took a risk to even go out, let alone go to a bar, let alone fight back against police,” she says. “But all of us who are queer share the risk we take in being ourselves.”

The display also features some lighter fare, including buttons and posters from various pride celebrations; a record from writer and musician Edythe Eyde (who recorded under the name “Lisa Ben,” an anagram of “lesbian”); and even a metal harness, complete with a codpiece, from San Francisco.

And Waters isn’t the only cultural icon to be represented in the exhibit. The full costume from figure skater Brian Boitano, who came out publicly after joining the U.S. Olympic delegation in Sochi amid outcry about Russia’s anti-gay laws, is joined by the tennis racket and ballet flats from Renée Richards, a transgender woman who fought for her right to compete at the U.S. Open. (Ott says she learned a new term, “woodworking,” when she went to meet with Richards. The notoriously private athlete said she and other transgender people made this their goal; they simply wanted to fade into the woodwork and live their lives after transitioning, without being noticed or questioned.)

All in all, Ott estimates the museum has the most comprehensive gay history collection in the country. None of these items were brought in specifically for the current display, but are part of a larger effort over the past four decades to build the museum’s collections on gay history, says Franklin Robinson, an archives specialist who is coordinating the documents and photos for the exhibit.

The collections are complemented by more than 150 cubic feet of archival material. And that’s only counting objects sorted as overtly LGBTQ-related; as Robinson points out, there is probably material in other collections that would also be relevant, since gay history is so intertwined with the broader story of the U.S.

“One of the points is that it's all part of American history. There’s lots of American history that people don't necessarily want to either hear about or see,” Robinson says. “But at the same time, our job is to document the American experience. And this is part of the American experience, like it, love it, don't like it.”

The museum has acknowledged LGBTQ history in some past exhibits, Ott says. While the American History Museum created a display for Stonewall’s 25th anniversary as well, it was significantly smaller, and visitors’ reactions, as gauged by the comment book from the exhibit, were divided at best.

For the current display, Ott says she’s felt a lot of support from others at the museum. Dozens of team members have been enthusiastically working to bring the display to life—from offering insights on the display’s message and focus, to styling costumes and building specialized mounts for each item. Smithsonian Channel will also release a documentary June 24 titled “Smithsonian Time Capsule: Beyond Stonewall,” which features interviews with Ott and Robinson.

Society as a whole has also changed rapidly in recent decades, Robinson points out. The path forward hasn’t been smooth—particularly in the past few years, policies and attitudes regarding LGBTQ people have seemed to backslide. Still, as a whole Robinson believes the nation is moving toward tolerance, making it “less and less scary” to put on an exhibit about gay history.

In return, Ott believes acknowledging gay history will help bring about more acceptance and make life safer for LGBTQ people. Through this exhibit, she wanted to allow members of the LGBTQ community to see themselves reflected in a collective experience and know they are not alone.

“For me, personally, the main audience, the focus audience, was the queer community,” Ott says. “We packaged it in a way that everybody could understand it. But that community, I want them to feel validated, and excited, and happy, and proud.”

"Illegal to be You: Gay History Beyond Stonewall," debuted June 21, 2019 and closes July 6, 2021, at the National Museum of American History and remains on view indefinitely.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/0a/b40ae2eb-1ed0-447c-abab-97821c3e1138/chrome_harness_jn2019-00800.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Maddie_3.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Maddie_3.jpg)