The beloved sitcom "M*A*S*H," set in an Army field hospital during the Korean War, hit airwaves in September of 1972, a little under three years before the United States’ withdrawal from Vietnam, and ended in February 1983, about eight months before the U.S. invasion of Grenada.

Slyly reckoning with the fact that in the latter half of the 20th century, war would become a more-or-less constant of American life, the show evolved over the course of its 11-season run, to become more thematically daring and complex. Set in a war-time MASH unit, or Mobile Army Surgical Hospital, the show followed the lives of the doctors and nurses, some of whom had been drafted and some of whom had volunteered, as they argued, clowned around, and—most of all—worked themselves past the point of exhaustion trying to save and comfort the wounded and dying. Ryan Patrick, co-host of the podcast “M*A*S*H Matters,” described the show as “pro-humanity” rather than strictly antiwar, but certainly war’s tragedies and absurdities were the subject of much of its comedy—and, increasingly in the later seasons, of its drama.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/a0/81/a081451c-7fb6-4763-923e-73a14a169a03/gettyimages-99885948.jpg)

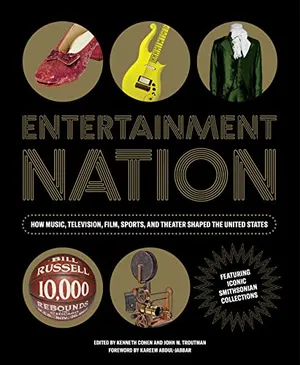

Entertainment Nation: How Music, Television, Film, Sports, and Theater Shaped the United States

Entertainment Nation is a star-studded and richly illustrated exhibition catalog from Smithsonian Books, celebrating the best of 150 years of U.S. pop culture. The book presents nearly 300 breathtaking Smithsonian objects from the first long-term exhibition on popular culture, and features contributors like Billie Jean King, Ali Wong and Jill Lepore.

The TV show, co-created by Larry Gelbart and Gene Reynolds, was loosely adapted from Robert Altman’s 1970 movie of the same name, which had been loosely spun off from Richard Hooker’s eponymous 1968 novel. Altman’s film had been a hit, but Gelbart and Reynold’s "M*A*S*H" was a phenomenon. An estimated 106 million people watched its two-and-a-half-hour final episode in the winter of 1983. It’s still the highest-rated episode of scripted television in history.

It’s uncommon for an innovative and challenging specimen of culture also to be massively popular. "M*A*S*H" was both. The show “changed the space that sitcoms operated in,” says Ryan Lintelman, entertainment curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History, evolving over the course of its run into a television series “that really delved into psychology and captured the post-Vietnam antiwar moment.”

The show’s cultural footprint was big enough to warrant a blockbuster exhibition at the museum that opened five months after the final episode aired. Featuring props, costumes, scripts, and two complete sets used in the production of the show—the operating room and the shared quarters that bunkmates “Hawkeye” Pierce (Alan Alda), “Trapper” John McIntyre (Wayne Rogers), and Frank Burns (Larry Linville) christened “The Swamp”—"M*A*S*H: Binding Up the Wounds” was enough of a draw to require the implementation of a timed-entry system and two extensions. By the time the exhibition closed in February 1985, 1,073,849 visitors had filed through.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/17/4b/174b2266-3973-41d5-94a9-1edf56a70652/gettyimages-57617374_copy.jpg)

The exhibition was unique in other ways, says Lintelman. When the show wrapped, 20th Century Fox offered to donate the artifacts, along with $60,000 to help cover exhibition costs, on an all-or-nothing basis, meaning the museum had to accept the entire collection. That’s actually caused some problems, says Lintelman candidly. The collection is too large to show in its entirety, and because of its size, difficult to store. The sporadic availability of the objects has sometimes created the impression among the latter-day "M*A*S*H" fandom that these treasures “are being kept from them,” Lintelman adds.

The good news is that one of the most recognizable elements of the collection—the signpost that adorned the show’s fictional 4077th, whimsically indicating direction and distance to Seoul as well as to Boston, Coney Island, Death Valley and other far-flung destinations stateside—will have prominent placement in the sprawling 7,200-square-foot exhibition, “Entertainment Nation,” opening December 9. This viewing marks the first time the "M*A*S*H" prop has been on display since 2012.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/87/fe/87fe216c-2463-4d8a-963a-e9cf40528a38/smithsonianbrochure.jpeg)

The piece is both an artifact of the production and a metaphor for its sensibility. “It’s a visual representation of the sense of the humor of the show,” Lintelman says, “and of the limbo its characters were living in.”

While the sign may not be quite as famous as some of its neighboring artifacts going on display in the upcoming exhibition, like Dorothy’s ruby slippers from The Wizard of Oz or Jim Henson’s original Kermit the Frog puppet, the "M*A*S*H" prop remains an object of public fascination.

Three were built during the production. One was lost in a fire that damaged the exterior sets so badly during the final season that the blaze had to be written into the show. The particular sign in the collection was used on a soundstage, Lintelman says. “We were lucky to get one that hadn’t been standing out in the sun for years.”

While "M*A*S*H" famously built its audience slowly following a relatively low-rated initial season, the massive cultural penetration the series eventually had is the product of a vanished era. There are simply too many options now for any single TV show (or streaming or cable series) to dominate its era the way "M*A*S*H" did.

But what about the "M*A*S*H" fans who were not yet born back then? Because make no mistake: The "M*A*S*H" millennials are out there.

“The series has never really dated,” says Patrick, whose podcast just released its 90th episode. “The themes of the show are universal, and they stand the test of time. The idea of finding humor and finding ways to cope in the midst of madness. I think that’s one reason that a lot of people returned to "M*A*S*H" during the pandemic,” he says.

Patrick’s co-host is Jeff Maxwell, who played mess hall staffer Pvt. Igor Straminsky for more than 80 episodes beginning with the show’s second season. The pair met in the late 90s when Maxwell was promoting his book The Secrets of the M*A*S*H Mess: The Lost Recipes of Private Igor. The pair kept in touch, and when Patrick reached out to Maxwell to inquire about his interest in perhaps being a recurring contributor to the M*A*S*H podcast he was contemplating, Maxwell did him one better, saying he’d be open to co-hosting.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/f5/f4/f5f4aac2-24b6-4855-a56c-6463f5d0b918/dsc07526_edited.jpg)

Along with sharing Maxwell’s recollections from the production, the two hosts frequently read emails on the show from millennials and even Gen Z listeners who have found "M*A*S*H" through its various reruns and home video and streaming releases.

One of those "M*A*S*H" millennials is Eric White, whose blog The M*A*S*H Historian highlights his collection of teleplays from the series along with other documents and ephemera from the production. “The first time my parents let me stay up to watch the ball drop on New Year’s Eve, we missed the ball because "M*A*S*H" was airing on another station,” he says.

White says he enjoyed the reruns when he saw them with his parents, when Fox began releasing full seasons of "M*A*S*H" on DVD in 2001, the opportunity to watch the episodes unedited and in sequence helped his casual fandom to bloom into something more ardent—and eventually, scholarly.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/52/16/52164f99-c907-471f-9c6c-90f5296882d5/gettyimages-99882181.jpg)

He wrote a paper about depictions of women on television like June Cleaver on “Leave It to Beaver” and Roseanne Barr’s fictionalized analogue on “Roseanne.” But he took a particularly keen interested in the character of Chief Nurse Margaret "Hot Lips" Houlihan, played by Sally Kellerman in the film and Loretta Swit in the TV series. Initially the target of misogynistic pranks, particularly in Altman’s movie, the character grew more nuanced and independent over the run of the series.

White notes that while the TV show stopped having other characters refer to Houlihan as “Hot Lips” fairly early, she was identified that way in the scripts right up until the finale. As he was earning his master’s degree in history, White became more interested in the methods by which Gelbart and Reynolds, as well as the writers and producers who took over the show in its later seasons, used interviews with veterans to generate storylines.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/fe/0c/fe0c1b4e-700e-499e-ac4d-0df517483116/jn2020-00360.jpg)

White bought his first "M*A*S*H" script in 2007, and created the site where he writes weekly posts about his collection last year. He says he has about 90 left to acquire (he keeps a spreadsheet, like any serious collector) from the complete run of 251. (The actual number of "M*A*S*H" episodes sometimes given reflects the fact that a few of the 251 scripts were shot as longer episodes that were later divided when shown in syndication, White notes.) Tracking down these treasures has occasionally led to happy interactions with people who worked on the show. “I bought a collection of scripts that had belonged to the wardrobe director, Albert Frankel,” he says.

“The most gratifying find was an original script from the finale,” White continues.

“I looked for the pilot as well; that’s a harder one to find. In the early seasons it wasn’t as popular, so finding scripts from Season One is pretty crazy. I have some original bound scripts that belonged to Jackie Cooper,” who directed 13 episodes of the show. “I bought those from his son.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/69/ad/69ad6855-2653-4e96-9617-24e99325dde0/gettyimages-99882662.jpg)

White plans a trip to the Smithsonian to see the signpost once “Entertainment Nation” opens. Near the end of our Zoom interview, he holds up a miniature replica of it that he keeps on his desk.

"M*A*S*H Matters" co-hosts Patrick and Maxwell are traveling already. They spent September 17, 2022, the 50th anniversary of "M*A*S*H’s" debut at Malibu Creek State Park, the former site of the “Fox Ranch,” where the show’s exterior scenes were filmed.

(In addition to standing in for Uijeongbu, South Korea, on "M*A*S*H," Fox Ranch was also a key filming location for Altman’s feature film version, along with dozens of other film and TV productions.)

Reached by email, Maxwell shared his memories of the famous signpost: “The signpost was certainly an accurate representation of those created during many wars,” Maxwell writes. “In the face of a life and death life, I’m sure they reflected for their builders an expression of love, remembrance, and a touchstone to home. The signpost was that same touchstone for everyone inhabiting the 4077. Interestingly, I think it served that same purpose for the millions of viewers around the world who recognized the ‘home’ they felt for "M*A*S*H."

“Plus, it was a very convenient place to hang your hat while waiting to shoot a scene.”

"Entertainment Nation" goes on view December 9, 2022 at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

Editor's note: September 21, 2022: This article has been edited to reflect the correct spelling of actor Loretta Swit.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

:focal(800x701:801x702)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/83/45/83458c09-0428-4ccf-9c28-ccfa90c88a52/untitled-1.jpg)