Fifty Years Later, Remembering Sci-Fi Pioneer Hugo Gernsback

Looking Back on a Man Who Was Always Looking Forward

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/4a/d5/4ad5ee5b-b739-45ff-8b7e-e0f5fa64e107/amazing_stories_1.jpg)

When expat Luxembourger Hugo Gernsback arrived in the United States in 1904, even he could not have predicted the impact his lush imagination and storytelling drive would have on the global literary landscape.

Young, haughty and dressed to the nines, Gernsback, who had received a technical education in Europe, soon established himself not only as a New York electronics salesman and tinkerer, but also as a prolific, forward-thinking publisher with a knack for blending science and style.

Modern Electrics, his first magazine, provided readers with richly illustrated analyses of technologies both current and speculative. Always sure to include a prominent byline for himself, Gernsback delved into the intricacies of subjects like radio wave communication, fixating without fail on untapped potential and unrealized possibilities.

Owing to their historical import, many of Gernsback's publications are now preserved at the Smithsonian Libraries on microfiche and in print, 50 years after his death on August 19, 1967. Enduring legacy was not on the young man's mind in his early days, though—his Modern Electrics efforts were quick and dirty, hurriedly written and mass-printed on flimsy, dirt-cheap paper.

With a hungry readership whose size he did not hesitate to boast of, Gernsback found himself constantly under the gun. Running low on Modern Electrics content one 1911 April evening, the 26-year-old science junkie made a fateful decision: he decided to whip up a piece of narrative fiction.

Centered on the exploits of a swashbuckling astronaut called Ralph 124C (“one to foresee”), the pulpy tale intermixed over-the-top action—complete with a damsel in distress—with frequent, elaborate explanations of latter-day inventions.

To Gernsback’s surprise, his several-page filler story—which ended on a moment of high suspense—was a smash hit among readers. His audience wanted more, and Gernsback was all too happy to oblige.

In the next 11 issues of Modern Electrics, he parceled out the adventure in serial fashion, ultimately creating enough content for a novel, which he published in 1925.

Nothing gave Hugo Gernsback more joy than sharing his visions of the future with others, and with the success of his flamboyant “Romance of the Year 2660,” he realized that he had a genuine audience.

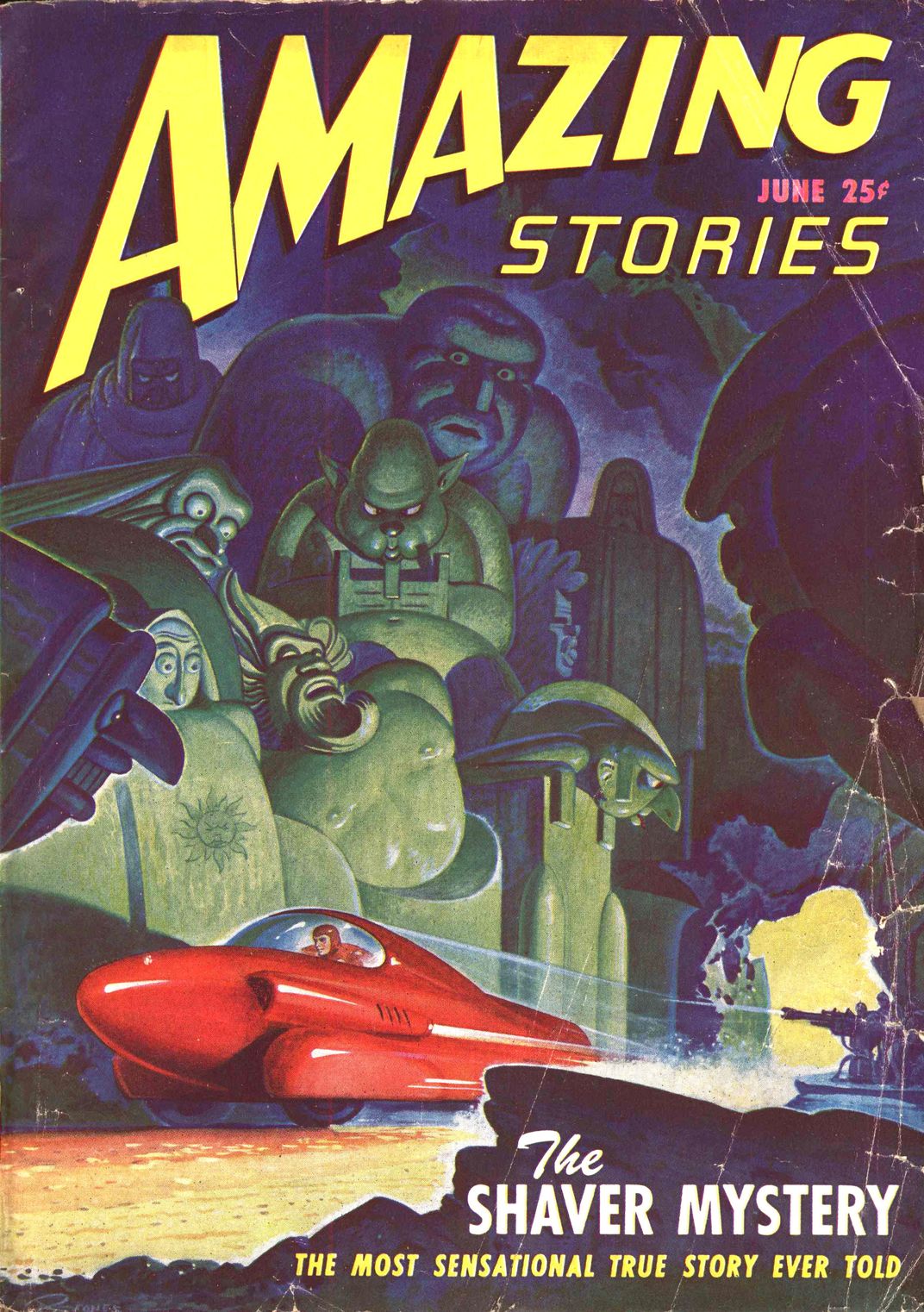

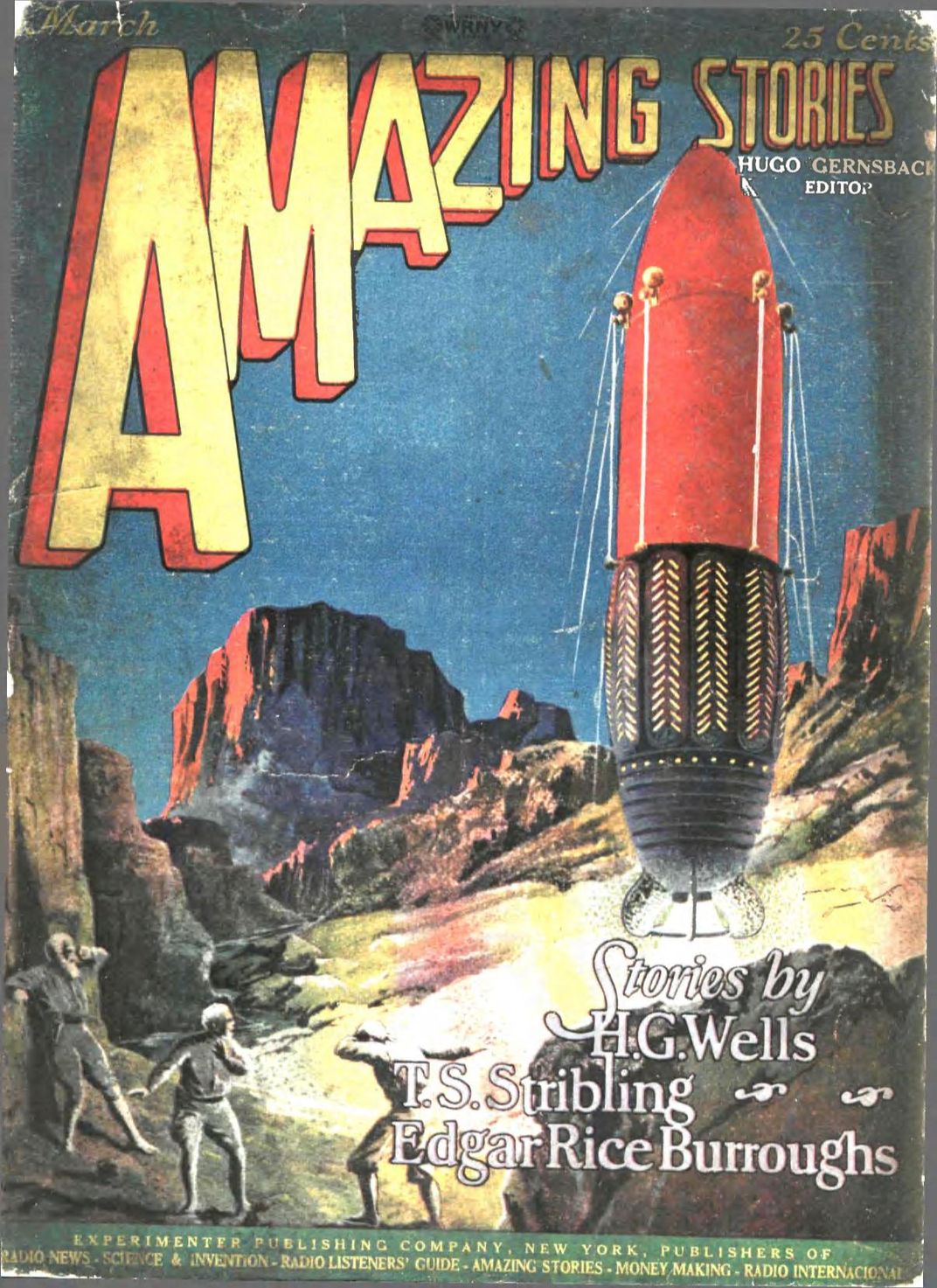

Eager to deliver exciting and prophetic content to his followers, Gernsback founded Amazing Stories in 1926, conceptualizing it as the perfect outré complement to the more rigorous material of Modern Electrics and the similarly themed Electrical Experimenter (first published in 1913). The purview of the new publication was to be “scientifiction”—wild tales rife with speculative science.

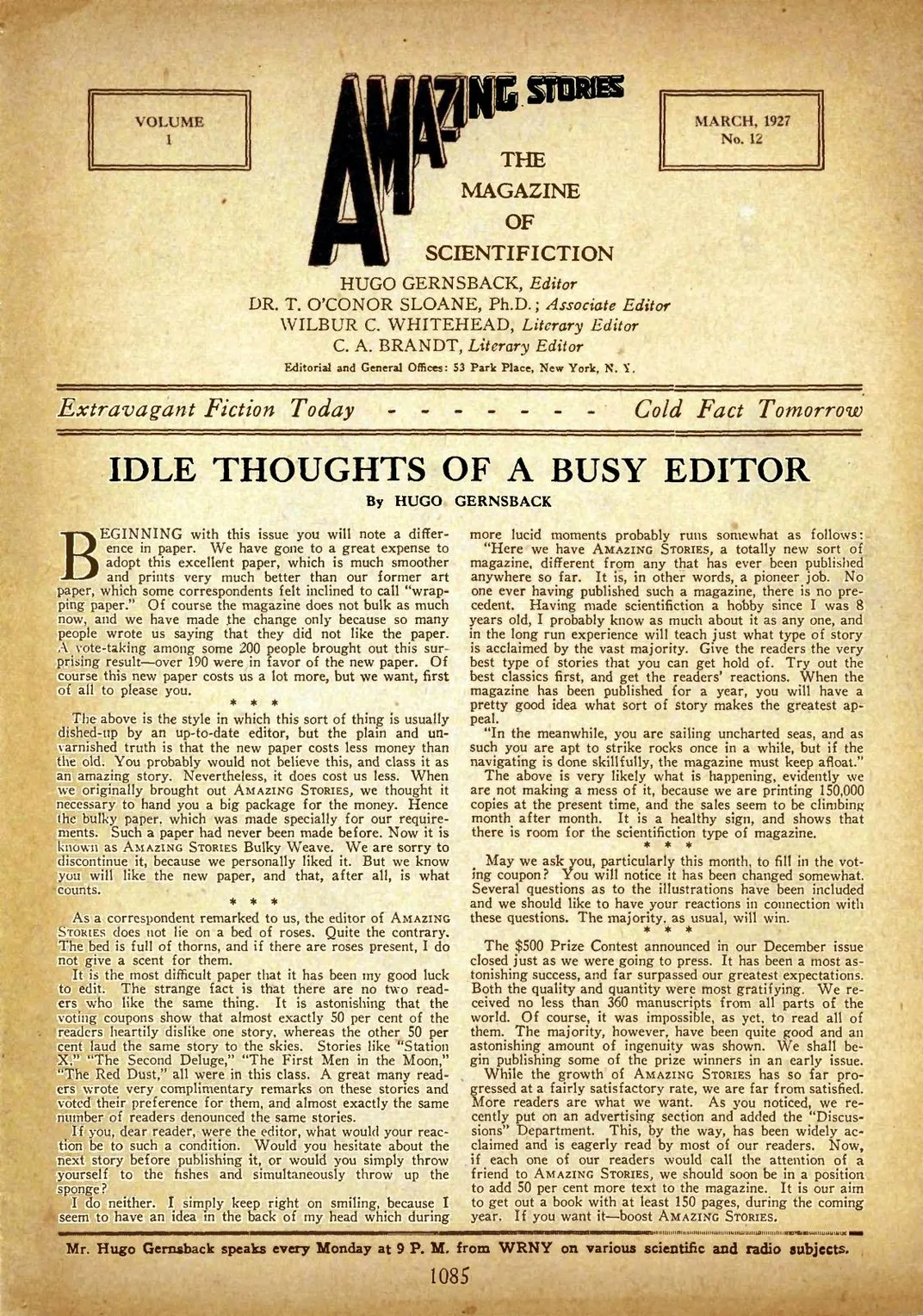

In an early issue of Amazing Stories, Gernsback laid out his foundational mission statement. "Having made scientifiction a hobby since I was 8 years old, I probably know as much about it as any one," he wrote, "and in the long run experience will teach just what type of stories is acclaimed by the vast majority." Within the text of the editorial note, Gernsback exhorted himself to "Give the readers the very best type of stories that you can get hold of," while recognizing fully that this would be a "pioneer job."

Gernsback wasn't the first to pen a science fiction story, granted—the inaugural issue of Amazing Stories featured reprints of H.G. Wells and Jules Verne, and indeed there are far older works that could plausibly fit the description. What he did do was put a name to it, and collect under one roof the output of disparate authors in search of unifying legitimacy.

In the eyes of prominent present-day sci-fi critic Gary Westfahl, this was a heroic achievement unto itself. "I came to recognize that Gernsback had effectively created the genre of science fiction," Westfahl recalls in his book Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction. Gernsback, he wrote, "had an impact on all works of science fiction published since 1926, regardless of whether he played any direct role in their publication."

Though Gernsback’s writing is at times stilted and dry, despite his best intentions, his laser focus on imagining and describing the technologies of tomorrow—sometimes with uncanny accuracy—paved the way for all manner of A-list sci-fi successors.

Isaac Asimov has termed Gernsback the “father of science fiction,” without whose work he says his own career could never have taken off. Ray Bradbury has stated that “Gernsback made us fall in love with the future.”

Hugo Gernsback was by no means a man without enemies—his ceaseless mismanagement of contributors’ money made sure of that. Nor is he wholly free from controversy—a column of his detailing a theoretical skin-whitening device is especially likely to raise eyebrows.

But while acknowledging such character flaws is, of course, necessary, it is equally so to highlight the passion, vitality, and vision of an individual committed to disseminating to his readers the wonder of scientific advancement.

It was for these traits that Gernsback was chosen as the eponym of science-fiction’s Hugo award, and it is for these traits that he is worth remembering today, 50 years after his passing. Between television, Skype and wireless phone chargers, the great prognosticator would find our modern world pleasingly familiar.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)