Finding Lessons for Today’s Protests in the History of Political Activism

A whirlwind of action, both organized and organic, supported by legal defense teams brought historic change

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/3e/14/3e142579-9afd-4fe3-8e41-f0e93267a524/blairwalkoutweb.jpg)

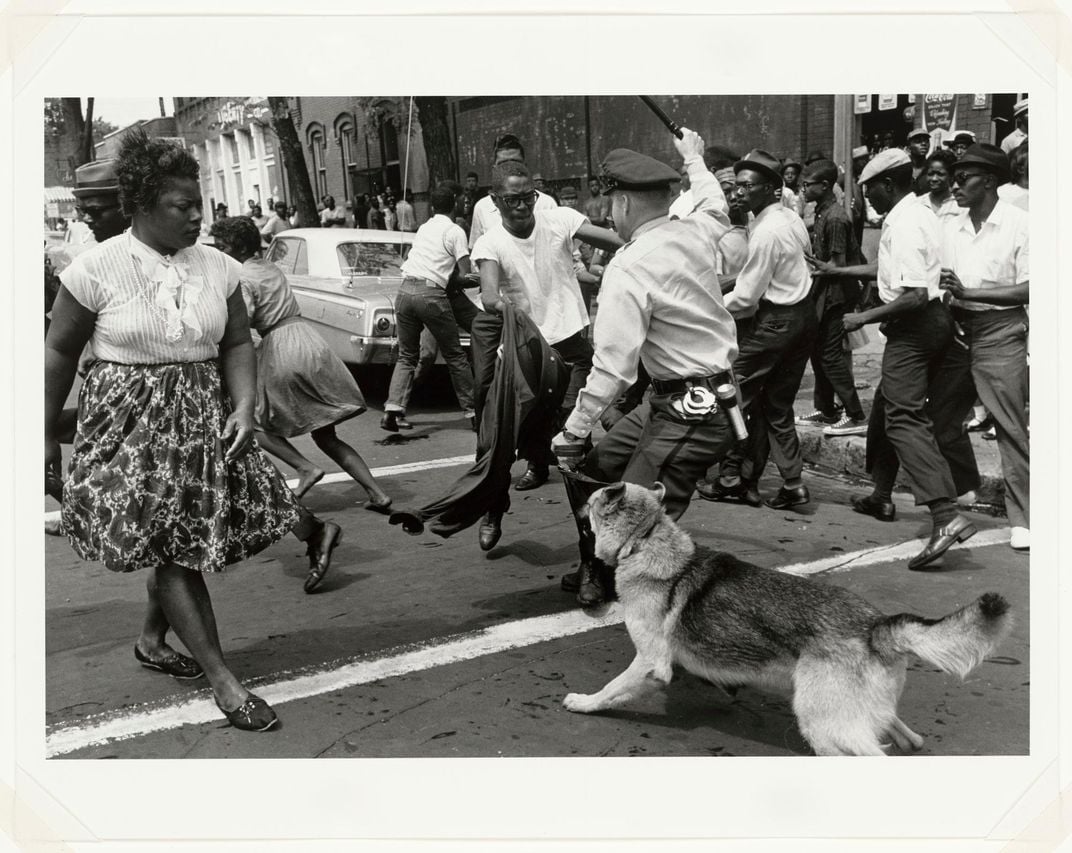

As demonstrators all over the country, many of them youth, began to protest after the recent election and its vitriolic and acrimonious tenor, others have questioned the value, the strategy and the timing of these protests. The time for activism, critics say, was before November 8. Ridiculing these protests as valueless today echoes what happened 50 years ago during the Civil Rights Movement.

The history of American political activism and involvement beyond the ballot certainly offers a template and lessons for such activism today and into the future. It sheds light on the concern that such actions by students across the country were ill-timed and ineffective—too little, too late.

“What we’ve witnessed in recent years is the popularization of street marches without a plan for what happens next and how to keep protesters engaged and integrated in the political process,” wrote the scholar and columnist Moisés Naím in his 2014 article for The Atlantic, “Why Street Protests Don’t Work.” Besides his references to social media, Naím's comments could have been written in the 1950s or '60s. “It’s just the latest manifestation of the dangerous illusion that it is possible to have democracy without political parties,” he wrote, “and that street protests based more on social media than sustained political organizing is the way to change society.”

Activists like Stokely Carmichael thought some of the most famous and iconic Civil Rights Movement events were a waste of time. He referred to the March on Washington as a worthless “picnic” and felt the only value of the celebrated Selma to Montgomery Voting Rights March was the grassroots organization he was able to do along the 54-mile journey down Alabama’s Route 80.

The history of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s suggests this concern to be right and wrong at the same time. Marches were a common method of protest during this era. Sometimes marches were part of a larger plan, while other marches grew organically and spontaneously.

Neither, however, was a guarantee of success or failure. Four years before he meticulously planned the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, organizer Bayard Rustin planned a different march down Pennsylvania Avenue called the Youth March for Integrated Schools. It was held on April 18, 1959 and brought together more than 25,000 participants, including such celebrities as Harry Belafonte, who would join the crowds on the Mall four years later.

The march was intended to expose the fact that five years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision by the Supreme Court, schools across the country were still segregated. Belafonte, in fact, led a delegation of student leaders to the White House to meet with President Eisenhower, but they were unceremoniously turned away as the administration had little interest in doing anything to enforce the Court’s ruling.

Impulsive protests sometimes had lasting effects. Following the spontaneous sit-in at the Greensboro, North Carolina, Woolworth store in February, students in Nashville, who had been taking classes run by Vanderbilt divinity student James Lawson in Ghandian nonviolent direct action tactics, leapt into action, launching a similar sit-campaign of their own. Those students included people whose names would become synonymous with the nonviolent Freedom Movement such as Marion Barry, James Bevel, Bernard Lafayette, John Lewis, Diane Nash and C.T. Vivian. After several months, however, they had seen few victories and no change in the law. Then, in response to the vicious bombing of the home of Nashville civil rights attorney Z. Alexander Looby on April 19, 1960 (though no one was injured), their resolve and impatience turned into extemporaneous action.

“The march on April 19 was the first big march of the movement,” organizer C. T. Vivian remembered on the PBS series “Eyes on the Prize.”

“It was what, in many ways, we'd been leading to without knowing it. We began at Tennessee A&I [college] at the city limits. Right after the lunch hour, people began to gather, and we began to march down Jefferson, the main street of black Nashville. When we got to 18th and Jefferson, Fisk University students joined us. They were waiting and they fell right in behind. The next block was 17th and Jefferson, and students from Pearl High School joined in behind that. People came out of their houses to join us and then cars began joining us, moving very slowly so they could be with us. We filled Jefferson Avenue; it's a long, long way down Jefferson.”

The multitude of young people decided to head to City Hall. They hadn’t planned the march in advance and had not gotten any confirmation from Nashville Mayor Ben West that he would participate or negotiate when they got there, but they continued on.

Vivian remembered, “We walked by a place where there were workers out for the noon hour, white workers and they had never seen anything like this. Here was all of 4,000 people marching down the street, and all you could hear was our feet as we silently moved, and they didn't know what to do. They moved back up against the wall and they simply stood against the wall, just looking. There was a fear there, there was an awe there. They knew that this was not to be stopped, this was not to be played with or to be joked with. We marched on and started up the steps at City Hall, and we gathered on the plaza that was a part of City Hall itself. The mayor knew now that he would have to speak to us.”

When they got to the steps of City Hall, Mayor West came out to meet the students and took part in one of the most incredible, yet generally unknown moments of the movement.

Fisk University Diane Nash, with her uncommon eloquence and staggering conviction, confronted the mayor of a Southern city with cameras rolling. “I asked the mayor . . . ‘Mayor West, do you feel that's wrong to discriminate against a person solely on the basis of his race or color?’”

West said he was so moved by Nash’s sincerity and passion and felt he had to answer as a man and not as a politician. West admitted he felt segregation was morally wrong, and the next day the headline of the Nashville Tennessean read, "Mayor Says Integrate Counters." Four years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964 made segregation illegal, the impromptu student march spurred Nashville to become the first Southern city to begin desegregating its public facilities.

The African American History Program at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History has for more than 30 years worked to document and present the Freedom Movement in all its complexity from the experience of those at the grassroots up to the leaders who are household names. Part of that involves understanding how multifaceted and multifarious the movement was.

Many things were happening all at once—connecting, conflicting, building, diverting from one another all at the same time. When we look, we remember back at all of the Movement’s pieces and moments as leading to the ultimate legal victories of the Johnson administration legislation of 1964 and 1965.

So we always think of the various efforts as part of an overall plan, partly because we remember the Movement as the manifestation of the vision of the few leaders whose names we know. The history was much more complex, however.

When we remember the mid-20th century Civil Rights protests and compare it to today, we often think there was a grand plan in the past where that is absent today. But the truth is there wasn’t one, there were many and they were often competitive.

Lawyers filing and arguing lawsuits for the NAACP legal defense team, whose work was critical to many of the protests we now credit to Martin Luther King and others, were displeased that their efforts were uncelebrated by history.

NAACP executive director Roy Wilkins once said to King about the 1955 bus boycott that propelled him into the movement, “Martin, some bright reporter is going to take a good look at Montgomery and discover that despite all the hoopla, your boycott didn’t desegregate a single bus. It was the quiet NAACP-type legal action that did it.”

Although legal action did lead to the Supreme Court decision that desegregated buses in Montgomery, even a ruling by the Court wasn’t always enough to ensure great social change. Though the Court ruled in the Brown decision that school segregation was inherently unequal and unconstitutional, many Southern states simply ignored the ruling since there was no enforcement mandate given. Other states closed down their public schools entirely, opting to have no public education rather than integrate students.

The Civil Rights Movement shows us that protest isn’t effective in a vacuum and one type of activism is rarely effective all by itself. In 1995, for the 35th anniversary of the Greensboro Woolworth’s sit-in that took place on February 1, 1960, the Smithsonian presented a program called “Birthplace of a Whirlwind.”

It argued that the unplanned sit-in orchestrated by four college freshmen, Franklin McCain, Joseph McNeil, Ezell Blair, and David Richmond, began a tempest that spun out of control, powered by complementary forces the four freshmen didn’t know where there, stirring the imagination of previously unmotivated actors, and taking the movement in directions no one had anticipated. That the protests were not planned was important.

Like Rosa Parks's defiance and many other such acts, it captured people’s dreams. At the same time, just like today, most people thought it folly. How could a few kids sitting down and ordering lunch accomplish anything?

In 2008, we began a program at the National Museum of American History in front of the original Greensboro lunch counter. It was in essence a training program asking visitors to step back in time and put themselves into the sit-in movement and ask themselves whether they would have participated. Now that this protest has become a mythic part of American history, accepted as one of our ideals, most people assume they would.

Through our theater program, we tried to put some of the risk and uncertainty back in the history. We asked visitors to consider whether they would put their bodies on the line doing something that nearly everyone, even those who agreed that segregation was wrong, would say was damaging to the cause and doomed to fail.

People who go first take a great risk. They might get beaten, killed, ignored, ridiculed or defamed. But our history has shown us that they might also spark something. People like the Greensboro Four and the Nashville students sparked something.

As historian Howard Zinn wrote in 1964, “What had been an orderly, inch-by-inch advance via the legal processes now became a revolution in which unarmed regiments marched from one objective to another with bewildering speed.”

It took that whirlwind, but also the slow legal march. It took boycotts, petitions, news coverage, civil disobedience, marches, lawsuits, shrewd political maneuvering, fundraising, and even the violent terror campaign of the movement’s opponents—all going on in the same time.

Whether well-planned, strategic actions or emotional and impromptu protests, it took the willingness of activists in support of the American ideals of freedom and equality. As Bayard Rustin often said, “the only weapon we have is our bodies and we need to tuck them into places so wheels don’t turn.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kegley140407Wilson0014.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Kegley140407Wilson0014.jpg)