Finding the Sacks Appeal in a Collection of Holiday Shopping Bags

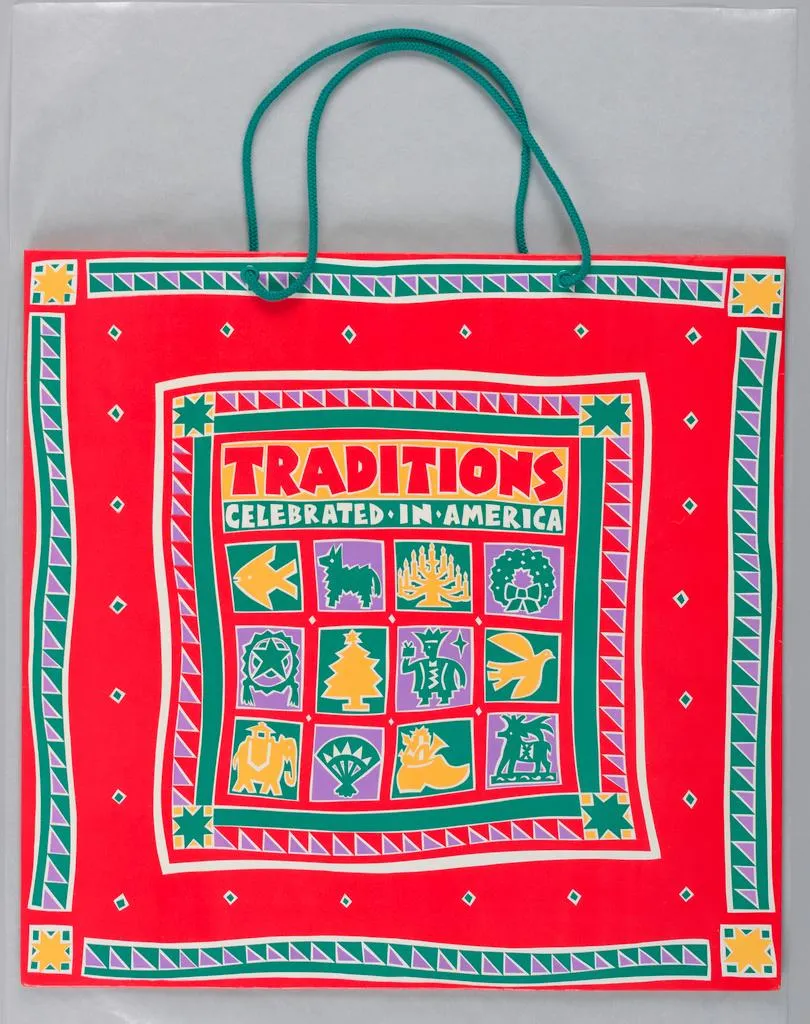

The Cooper Hewitt’s collection of some 1,000 bags reveals a few with some very cheery holiday scenes

At this time of year, the Consumer Confidence Index—the measure that gauges how we feel about reaching into our pockets and shuffling our decks of credit cards—rises to the point where it could be called the Consumer Irrational Exuberance Index. Streets and stores bustle with eager optimists; shopping proceeds guilt-free, since (we tell ourselves) the spending serves to make other people happy. And hardly a creature is stirring who isn't clutching that bright icon of the holiday season, the shopping bag.

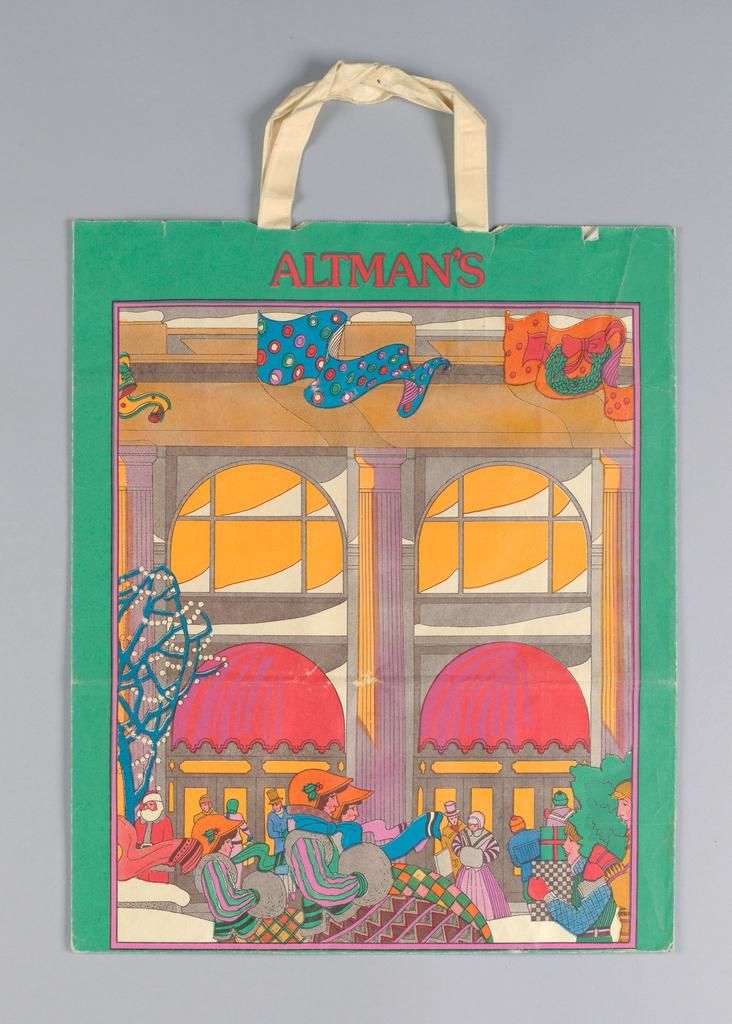

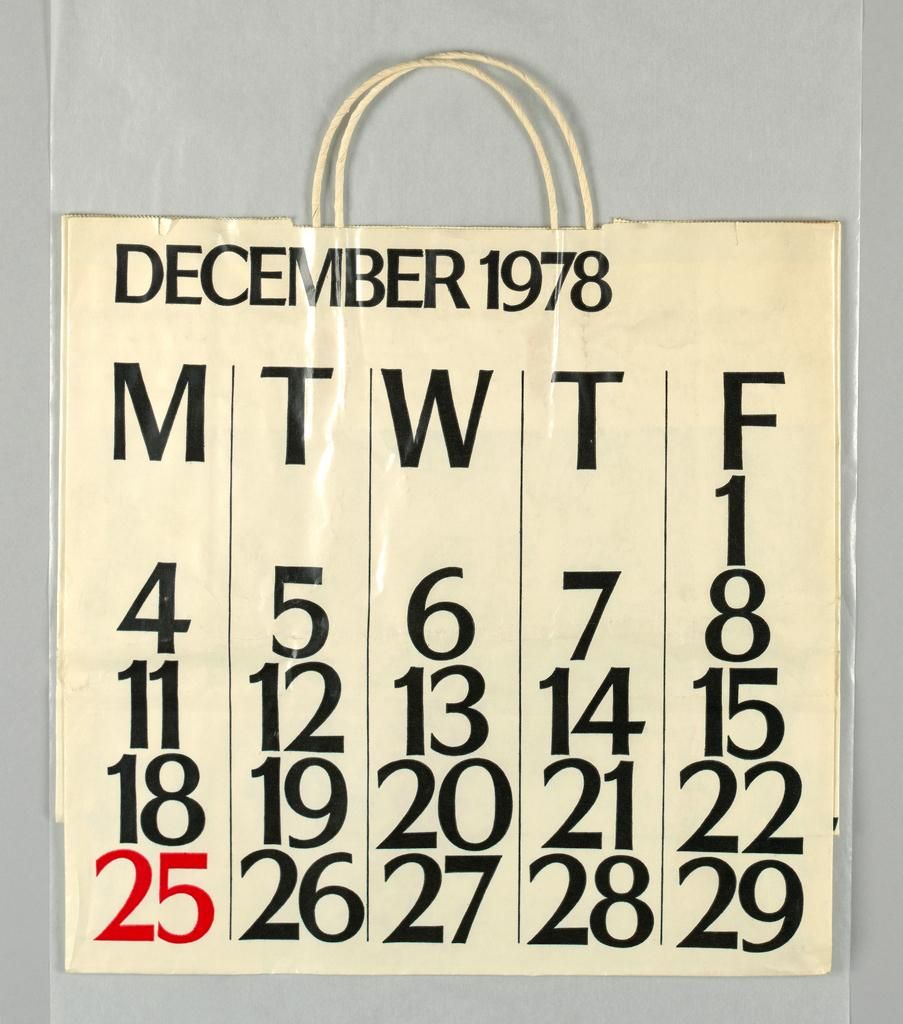

Shopping bags, those testimonial totes signaling the consumer preferences of those who carry them, by now constitute part of the nation's mercantile history. In 1978, the Smithsonian's Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum in New York City mounted an exhibit showcasing more than 125 bags-as-art, each the result of relatively recent marketing advances. "The bag with a handle attached cheaply and easily by machine has existed only since 1933," wrote curator Richard Oliver. " By the late 1930's the paper bag. . . was sufficiently inexpensive to produce so that a store could view such an item as a ‘giveaway.'"

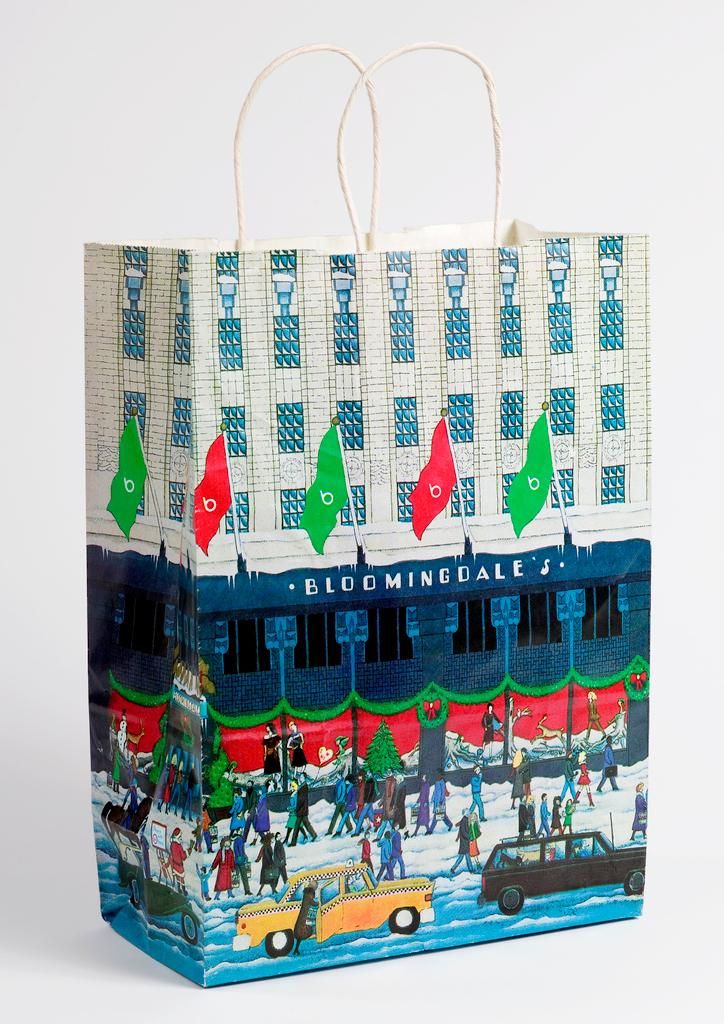

According to Cooper Hewitt curator Gail Davidson, the museum's collection has grown to some 1,000 bags, among them a cheery 1982 Bloomingdale's tote emblazoned with a holiday scene.

A signature bag, at least those from certain department stores, has long had the power to reassure the shopper. My mother used to venture into New York City only once or twice a year—to shop at Saks Fifth Avenue; the rest of the time, she patronized less glamorous New Jersey emporiums. But she always carried her purchases in carefully preserved Saks bags.

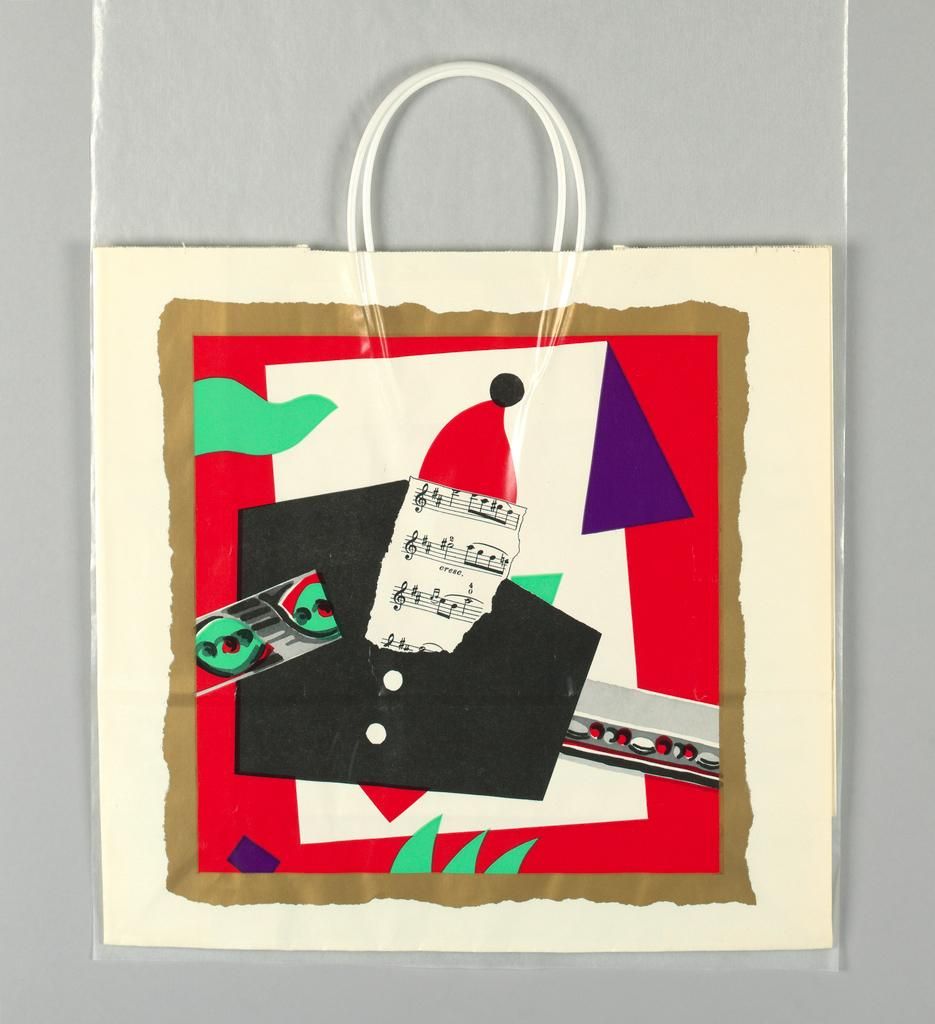

Until the 1960s, the shopping bag served to implement straightforward branding strategies, trumpeting, for example, the distinctive blue of Tiffany. By the 1980s, however, Bloomingdale's pioneered a more elaborate approach, introducing an ever-changing series of shopping bags: almost overnight, they came into their own as design objects. This innovation was the brainchild of John Jay, who took over as Bloomingdale's creative director in 1979 and guided the store's marketing until 1993.

Jay commissioned up to four or five bags annually, each featuring the work of various artists, architects or designers. "I wanted each bag to be a statement of the times," he recalls. "We did bags about the rise of postmodernism, the influence of the Lower East Side art movement, the Memphis design movement in Italy."

Architect Michael Graves, fashion illustrator Antonio Lopez and designer Ettore Sottsass, among others, produced the Bloomingdale's bags. The Bloomingdale's logo was not to be seen. (The Christmas bag pictured here, with its holiday depiction of the store itself, is a rare exception.) "The appeal for famous artists certainly was not the money," says Jay, "since we paid only $500, if that. But there was a creative challenge. We wanted to build a brand by constant surprise and creative risk—something that's missing from retail today."

Bag consciousness tends to be missing too, or at least is in decline. While some stores can still be identified by signature carryalls, Davidson observes that shopping bags are no longer the high-profile totems they once were. "I don't seem to see a real variety of bags these days," she says. "We still have some come in to the museum, but no longer in large quantities."

Bloomies' bags won awards and attracted press attention. Jay even remembers a photograph of President Jimmy Carter, boarding the presidential helicopter, a Bloomingdale's bag in hand. On the international scene too, bags morphed into symbols of quality. Rob Forbes, founder of the furniture retailer Design Within Reach, recalls that in the 1980s, he lined a wall of his London apartment with "incredible bags, very seriously made."

The last bag Jay commissioned, from Italian fashion designer Franco Moschino in 1991, caused a ruckus. It depicted a woman wearing a beribboned headdress, its color scheme the red, white and green of the Italian flag, adorned with the motto "In Pizza We Trust." After the Italian government objected to such irreverence, the bag was quietly pulled.

On eBay recently, I came across a green shopping bag stamped with the gold logo of Marshall Field's in Chicago, now a Macy's. The description under the item said simply: "The store is history." So, it seems, are the bags that we, our mothers, and even Jimmy Carter, dearly loved.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Owen-Edwards-240.jpg)