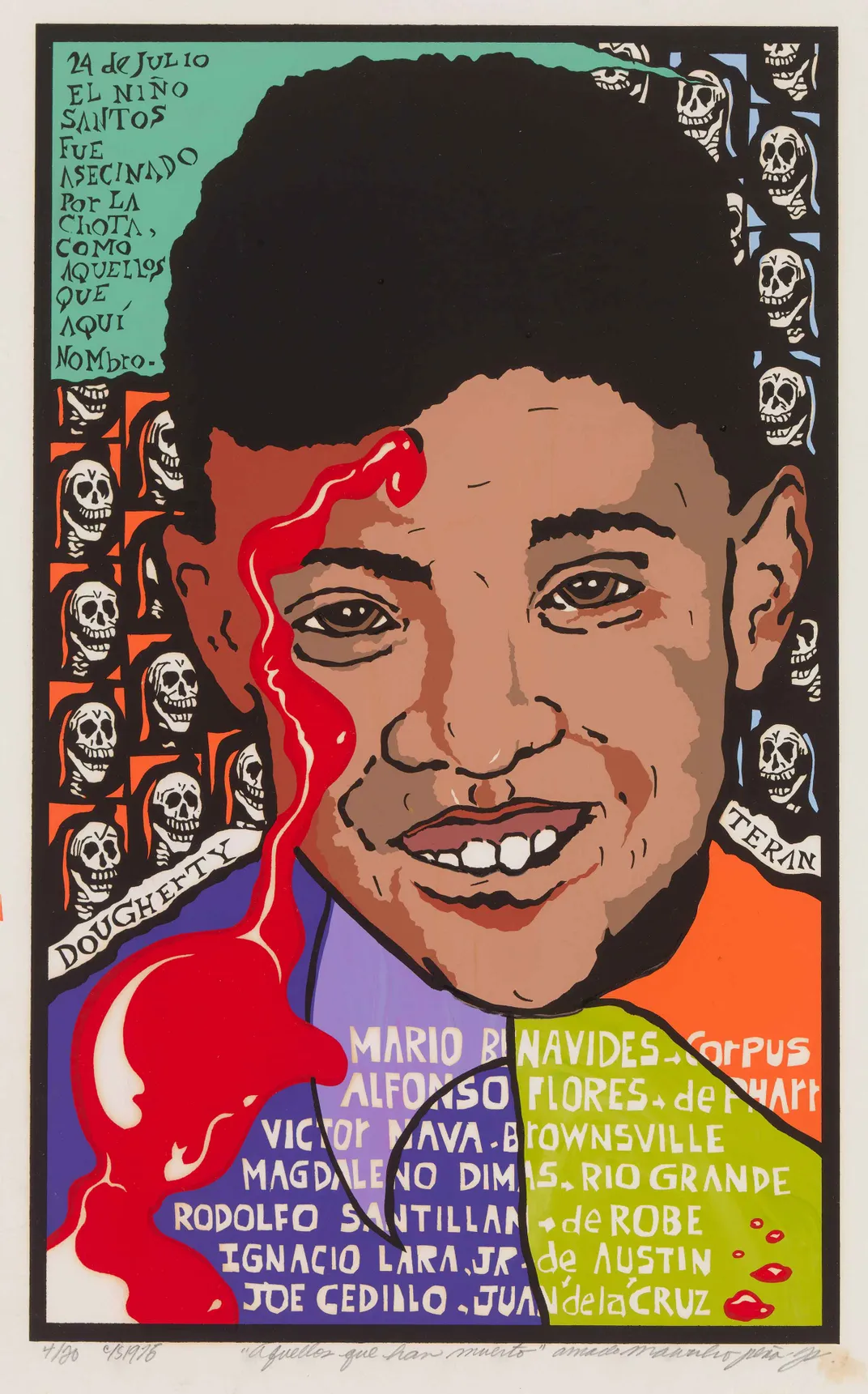

In the summer of 1973, Santos Rodriguez, a Mexican-American boy, was shot and killed by a Dallas police officer in a game of Russian roulette intended to elicit a confession out of Rodriguez. Twelve years old at the time, Rodriguez had, minutes before, been handcuffed and placed in the back of the cop car with his brother, David, 13. The pair had been accused of stealing $8 from a gas station vending machine.

Two years after the tragic murder, Amado M. Peña, Jr., a Mexican-American printmaker living and working in the Southwest, created a screenprint of Rodriguez’s portrait. Titled, Aquellos que han muerto, meaning “those who have died,” the work features Rodriguez’s face—with the boy’s endearingly large front teeth and soft glance typical of a child. Smirking skulls lurk in the background and a trail of blood pools towards the bottom of the frame next to the names of other Mexican-Americans who were killed by police violence.

“We see these issues that keep on recurring, that relate to how we’re still struggling to obtain equality in this country. This is the never-ending project of trying to live up to our ideals as a nation,” says E. Carmen Ramos, curator for Latinx art at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM). “It was really important to show how the issue of police brutality has a very long history for people of color in the United States.”

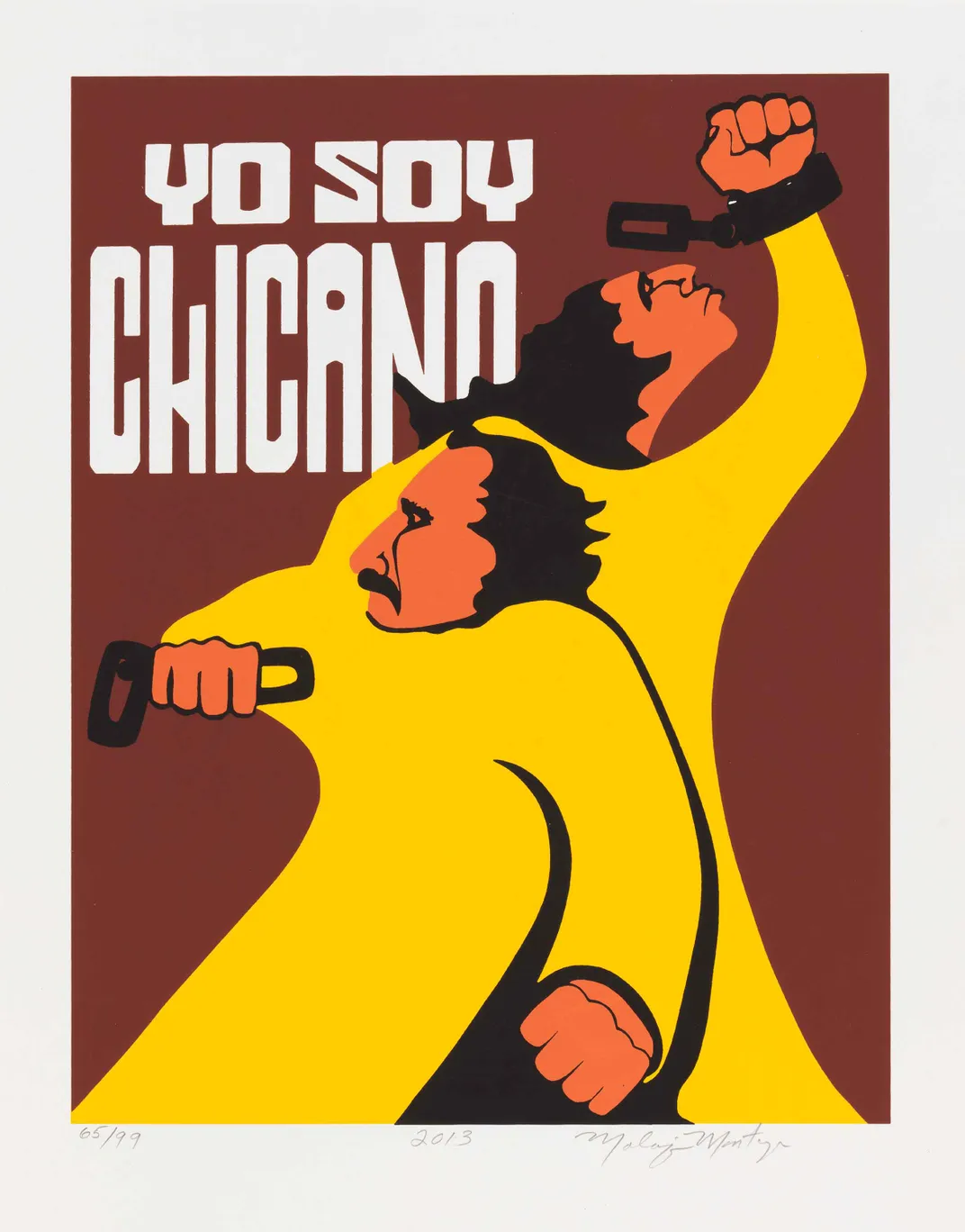

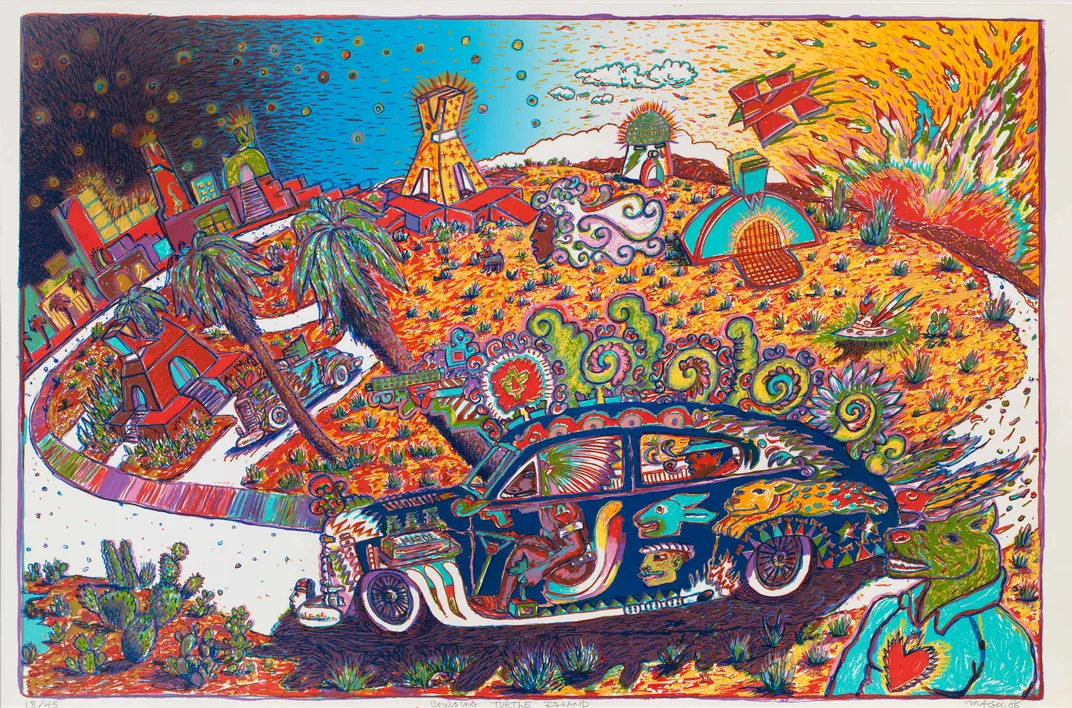

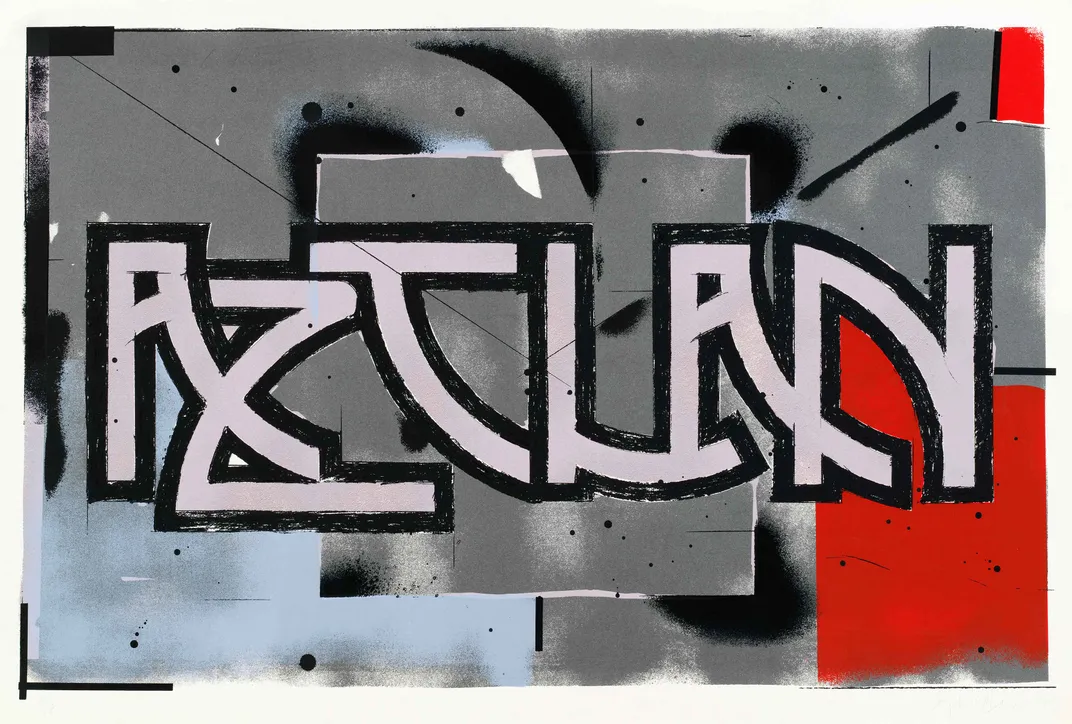

Aquellos que han muerto is on display at SAAM along with more than 100 other works in the exhibition, ¡Printing the Revolution! The Rise and Impact of Chicano Graphics, 1965 to Now. The show is currently on view virtually and in person as of May 14, when SAAM reopens after being closed due to Covid-19 precautions. This is the first show of its scale of Chicano works, and represents a coordinated effort by Ramos and her team to enlarge the Smithsonian’s collection of Mexican-American work.

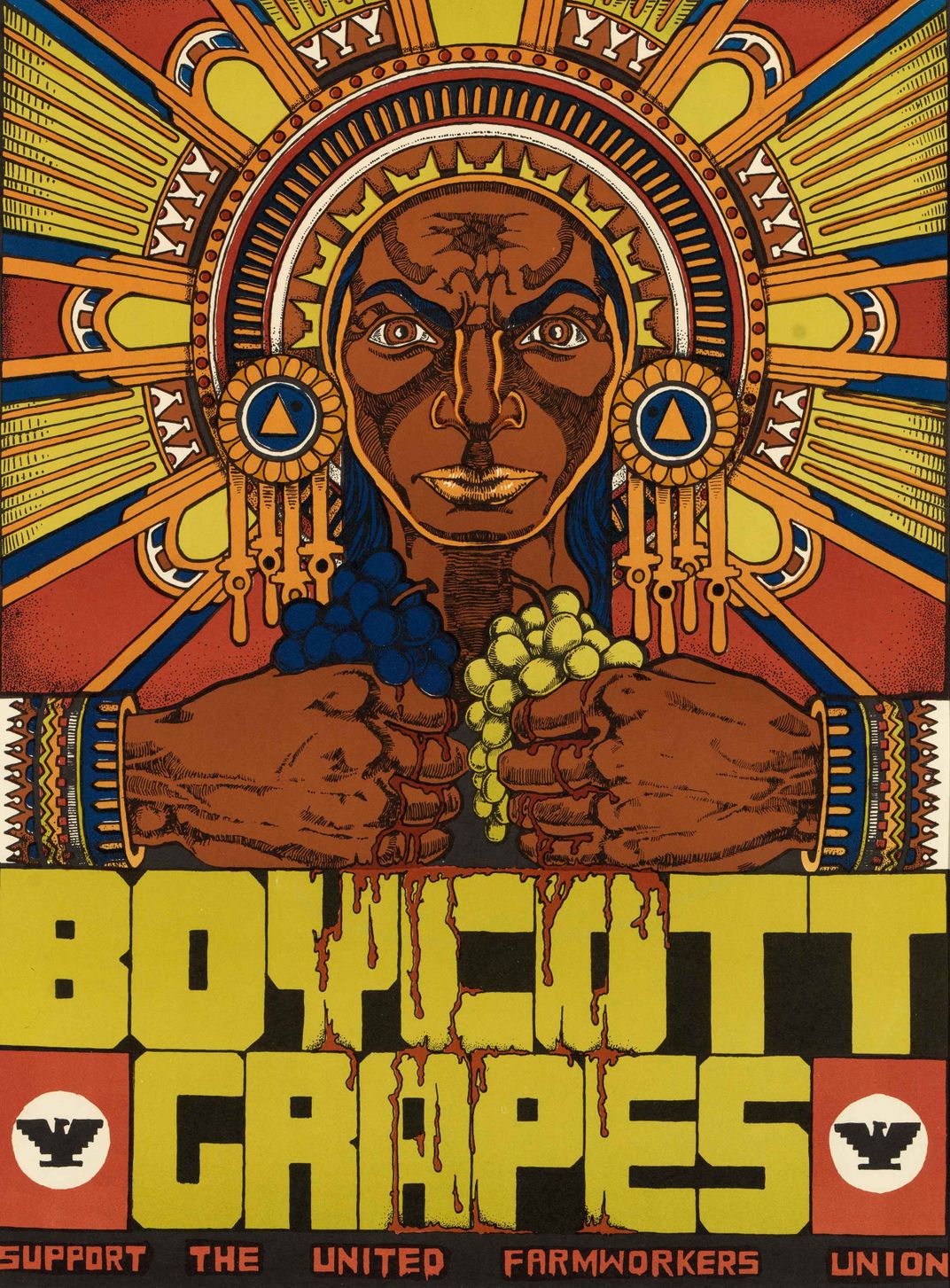

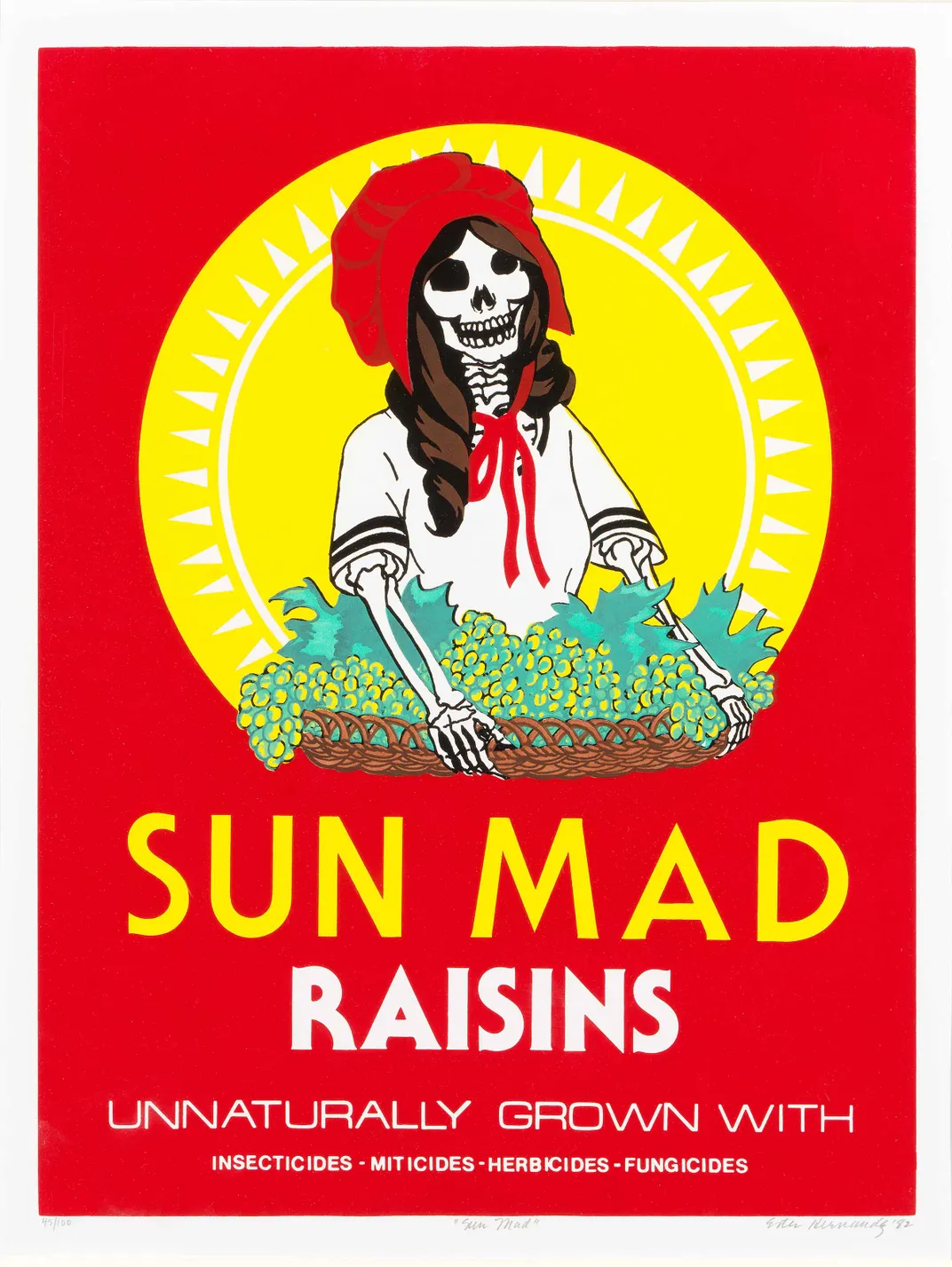

Featuring everything from political cartoons to posters, murals and graffiti, ¡Printing the Revolution! showcases the incredibly diverse ways in which Chicanos utilized the graphic arts medium as a method of protesting the institutional racism and systemic inequality they were, and continue to be, subjected to within white society. The term “graphic” encompasses not only posters but broadsheets, banners, murals and flyers that artists used to get their messages across, all of which represent different ways in which artists are supporting political causes.

Chicano posters and prints have a long history that originates with the rise of the Chicano Movement itself. As civil rights discourse took hold of the mainstream in the 1960s and ‘70s, Mexican-Americans, too, began to reimagine their own collective sense of identity and embrace their cultural heritage. This included the reclamation of the term Chicano, which, until then, had been a derogatory term. As Rubén Salazar, the pioneering Mexican-American journalist, described, the Chicano was a Mexican-American with a “non-Anglo image of himself.”

Also known as El Movimiento, the Chicano Movement mobilized the community through grassroots organizing and political activism. This included reforming labor unions, advocating for farmers’ rights, protesting against police brutality and supporting access to better education. By reaching a large number of people with their work, Chicano artists used this medium—which lends itself to being both a functional piece and a work of fine art—to engage directly with viewers and debate and redefine a shifting Chicano identity.

Displaying only one-fifth of the Smithsonian’s enormous Chicano graphic arts collection, the exhibition serves as an opportunity to acknowledge the powerful impact Chicano graphic artists have had on the field, and to put pieces from the past into conversation with those being made today.

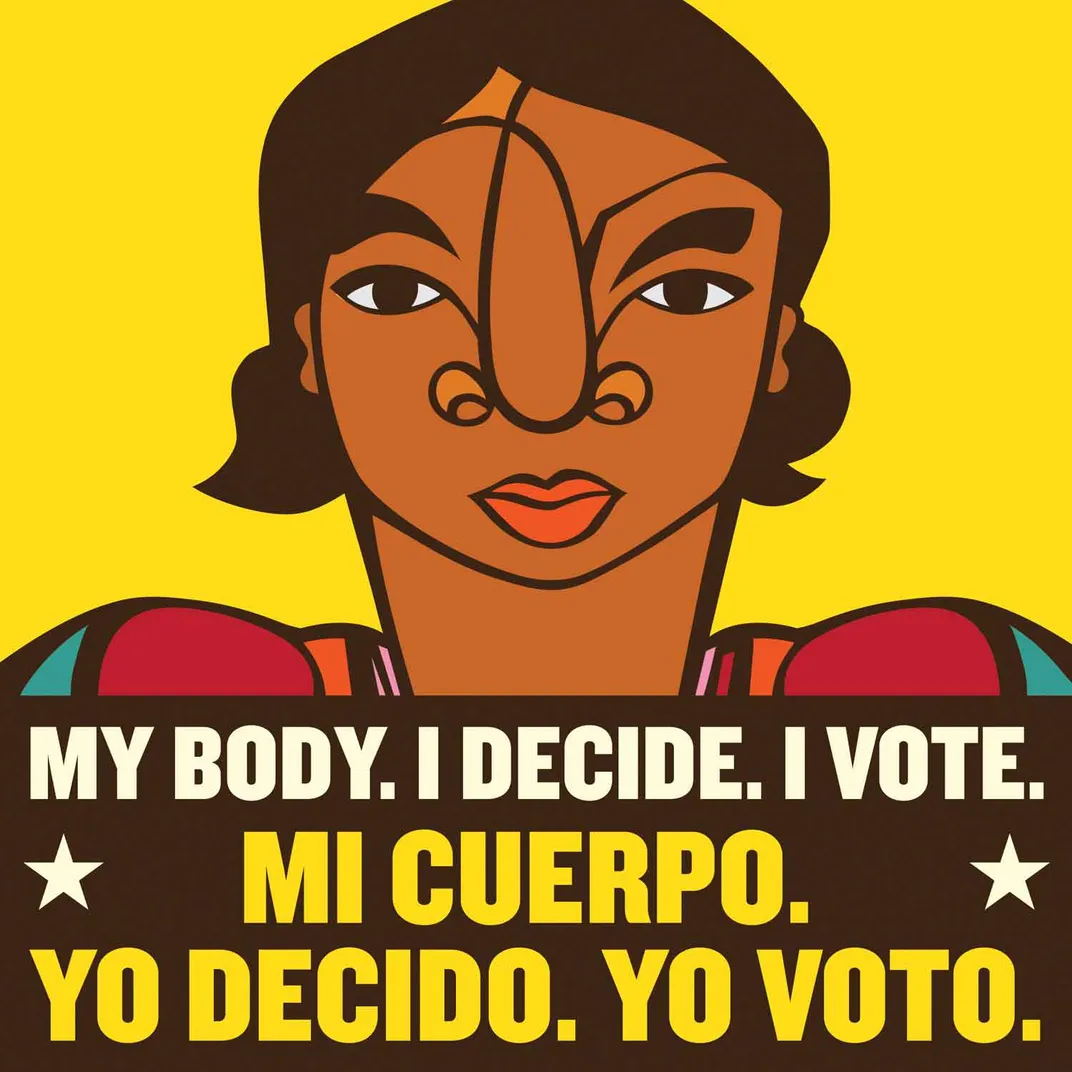

“We wanted to track how printmaking has changed in the last 50 years, especially when tied to issues of social justice. How have artists been innovating different approaches because of technology? That’s one thing our exhibition tries to tell,” says Ramos. “Technology is an extension of this long history. Today, artists are working in the same way—they’re just using digital platforms to spread their work.”

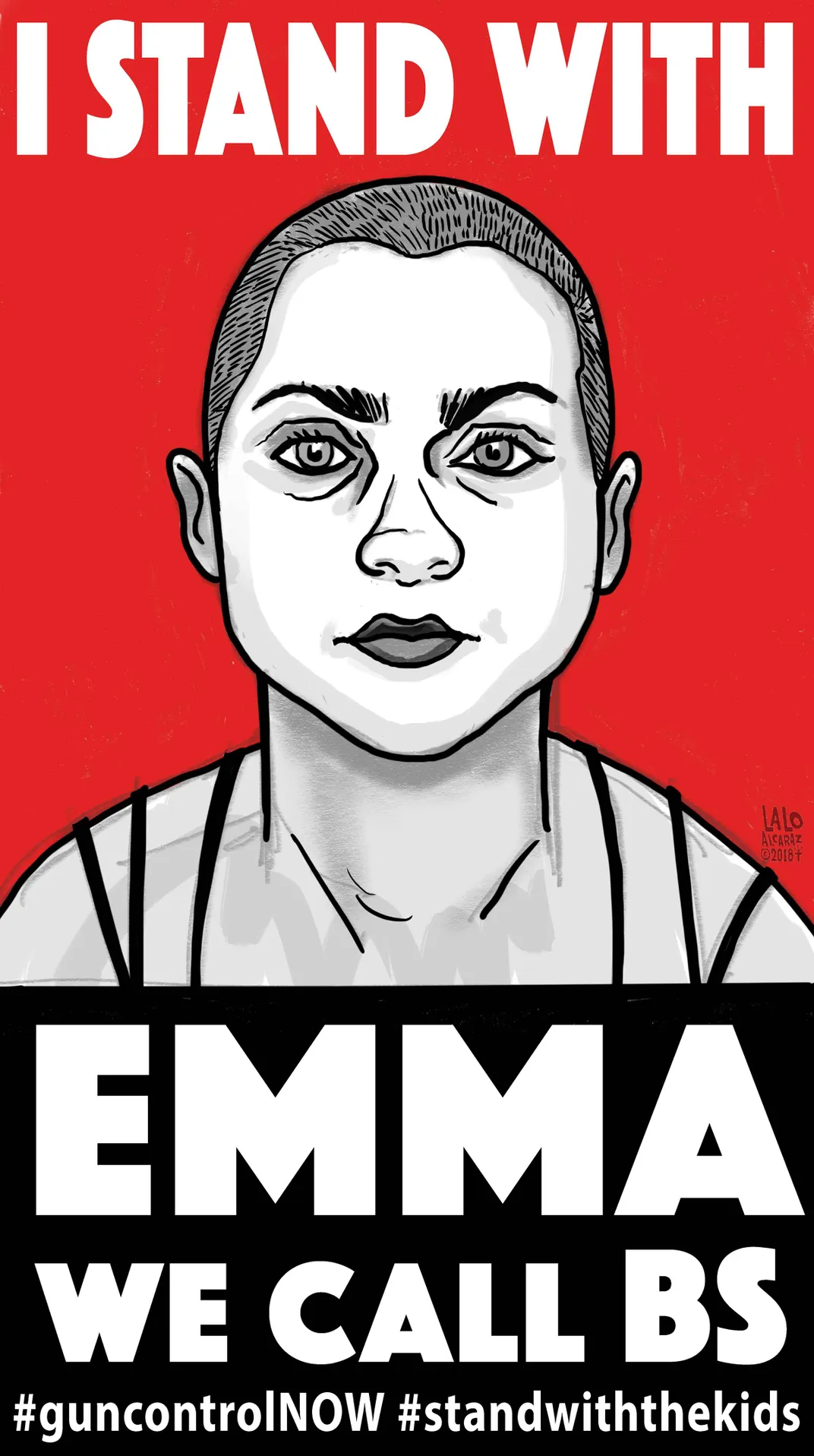

In fact, Ramos first found out about one of the show’s works through her own Facebook page. A portrait made by Lalo Alcaraz titled I Stand with Emma was made in the aftermath of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in February 2018. It depicts Emma Gonzalez, a survivor of the shooting, who went on to give her iconic “We Call BS” speech, demanding an end to mass school shootings. The speech quickly went viral and helped spark the March for Our Lives protests.

“I became aware of this print because I’m Facebook friends with Lalo,” explains Ramos, who was captivated by how Alcaraz was bringing the tradition of Chicano graphics into the 21st-century by not only creating a work digitally, but also sharing it through social media. “This is the same thing.” she says. “It’s a different platform, but this is part of the story that we’re trying to tell with this exhibition.” Like other viewers, Ramos downloaded the PDF of the image, copied it, and eventually acquired it for the Smithsonian’s collection.

In the print, Alcaraz deploys an austere use of color—the red background contrasts the bold but simple use of black and white—and a tight crop around the subject’s face draws viewers closely into Gonzalez’s glare. Her eyes sparkle, but they are framed by furrowed brows and bags under her eyes that tell readers she’s exhausted.

Claudia E. Zapata, a curatorial assistant of Latinx Art at SAAM and a digital humanities specialist, describes how the hashtags “#guncontrolNOW” and “#istandwiththekids” function as metadata that help situate Alcaraz’s work in the contemporary moment.

“I was interested in how digital strategies are creating a consciousness,” says Zapata. Ramos and Zapata wanted to show how artists today continue to use their work for political causes in new ways, analyzing how digital work introduces “questions that normally aren’t prompted in a printmaking show,” and exploring how artists are moving beyond a simple definition of digital art as a tool that isn’t just a new version of a paintbrush. These new versions can also include public interventions, installations and the use of augmented reality.

Zapata explains that it’s critical to consider the contexts in which these works are being created, which implies not only the moment in time of their production but also the ways in which the works are being duplicated. “It’s important to consider the context in which [the work] was shared and to get the artist’s voice. But when referring to open-source artwork, it’s also important to see, once it’s been shared, how the community commodifies it—not in the sense that they will change it, but in that the size may change, the form it takes may change,” Zapata says. For example, works get enlarged when they are projected against the side of a building.

Like the work of Chicano artists in the ‘60s and ‘70s, contemporary graphic artists are making work with the intention of sharing it. It’s just that social media and virtual platforms have replaced snail mail. As opposed to focusing on retail values, Chicano artists have, and continue to prioritize the immediacy and accessibility of what they are making. Which is why taking into consideration what communities do with these pieces is just as important as the artist’s original intention.

“Digital art continues the conversation and recognizes that Chicano artists are still producing,” states Zapata. [These pieces] are “still a radical resistance to oppression that’s never going to be out of fashion, unfortunately.”

In this sense, Printing the Revolution is, itself, a radical act of resistance. “Our exhibition is really about correcting the ways in which Chicano history has been left out of the national printmaking history,” says Ramos. “Simply collecting them and presenting them is a way to challenge that exclusion.” Indeed, it’s a step in the right direction.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/6f/a1/6fa1e484-39ad-4484-a4f5-32c7ab9a30a7/longform_mobile.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/ec/d4/ecd4e0fd-7559-4002-a466-56218c40340d/social-media-dimensions.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nili_2.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/nili_2.png)