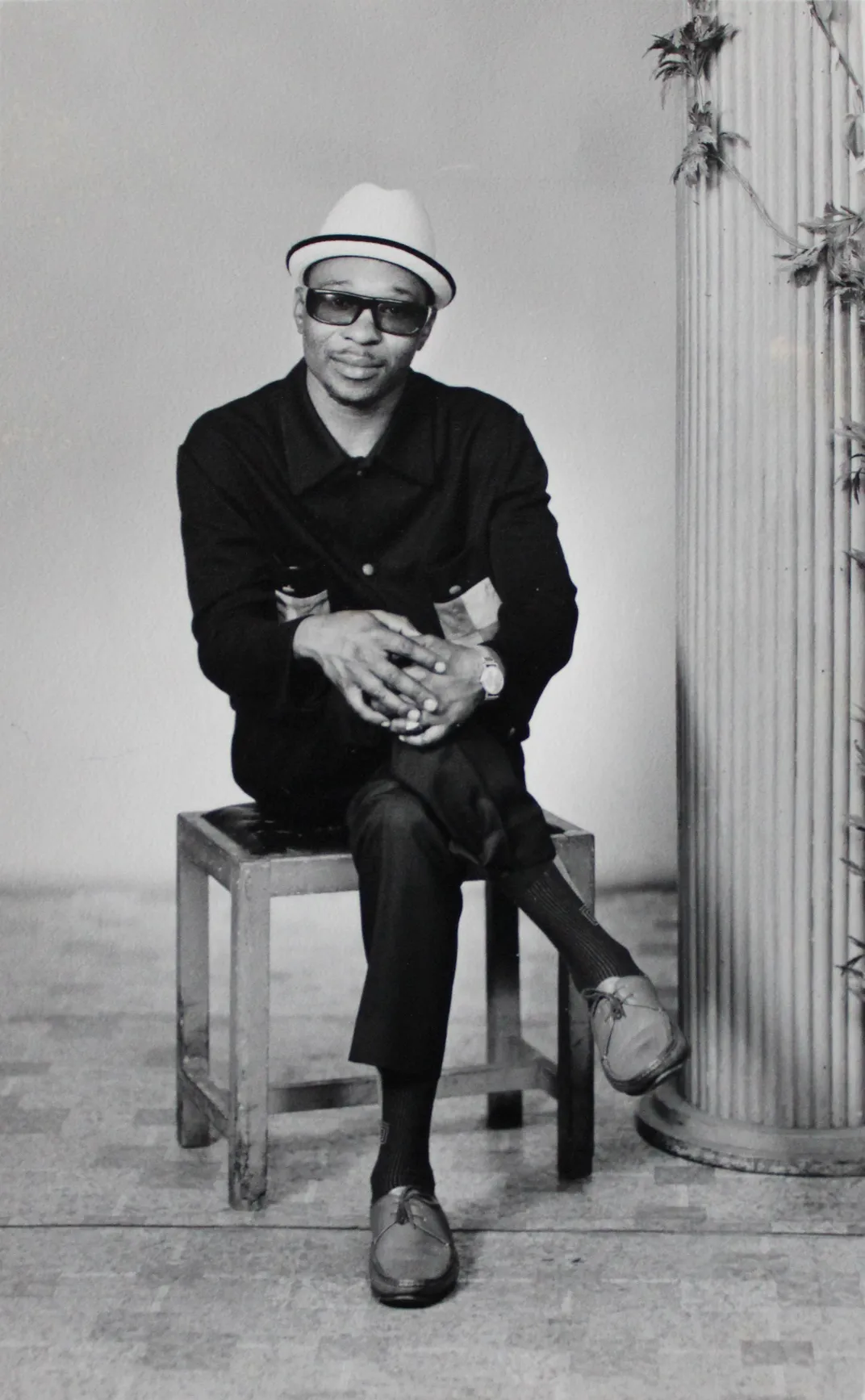

First Major Swahili Coast Art Show Reveals a Diverse World of Cultural Exchange and Influence

At the Smithsonian’s African Art Museum, international influences commingle to create a farrago of artisanal splendors

:focal(562x432:563x433)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f4/cb/f4cb2d2a-d218-428e-bbaa-0b14a3a472bd/17geary_157_tanzania.jpg)

Aside from the glittering jewelry, intricately carved ivory and woodwork, revealing photographs and cosmopolitan decorative items, a new exhibition on art from the Swahili Coast at the Smithsonian’s African Art Museum ultimately centers on words.

Both the oldest and newest items on display in World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Ocean, the first major exhibition dedicated to the arts of the Swahili coast in southeastern Africa, are both concerned with words.

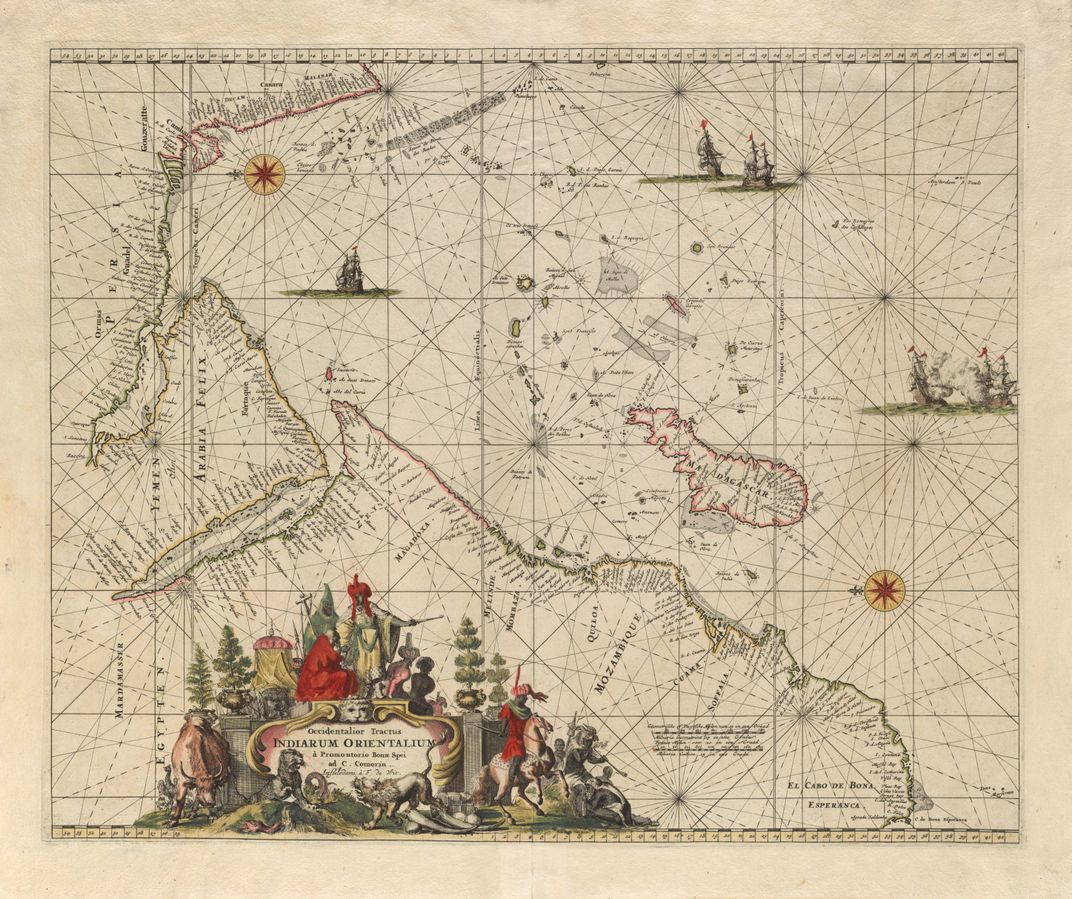

Tombstones carved from coral dating back to the 15th century combine their text with vegetal patterns and flowers; their forms recall stones from Egypt and Iran from the 12th to 15th century, emphasizing the Swahili Coast as a place where many cultures crossed, from both Africa and across the Indian Ocean to India and China.

But an array of super contemporary messages are to be found, artfully, on bicycle mud flaps from Zanzibar from only a dozen years ago whose phrases, translated, offer phrases such as “Work is Life,” “Maybe Later” and “All’s Cool my Friend.”

The flaps are on loan from the Fowler Museum at UCLA, one of 30 different loaning institutions from four continents that lent the 170 objects in the show that focuses on the arts of present day coastal Kenya, Tanzania, Somalia, Mozambique, the Indian Ocean Islands and mainland Africa.

Large historical examples of artworks from the region, which had been the site of important port cities since the 9th century, were impossible to transport for the exhibition, which first showed at the Krannert Art Museum at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. But in the tombstones from the ancient city-states of Mombassa and Gedi, lent for the first time from the National Museums of Kenya to North America for the first time, “you can see the incredible mastery of the local artisans who were carving these out literally out of the bedrock, the coral of the sea, into these great monuments,” according to Prita Meier, assistant professor of art history at New York University, and one of the co-curators of the show.

By using African calligraphic inscriptions that borrow from the Muslim culture of Egypt and Iran, Meier says, “they were playing with the languages of those places and covering those objects with the visual culture of the elsewhere, of faraway places.” And by carving these influences in coral, “they make permanent the fluidity of the Swahili coast,” she says. “They’re really exquisite pieces.”

At the same time, the mud flaps reflect how important the word remains in the culture of the region, according to Allyson Purpura, senior curator and curator of Global African Art at Krannert, where she spent several years with Meier putting World on the Horizon together.

“Everyday quotidian objects like a bicycle mud flap now is being embellished by the word,” Purpura says. “The word is the agent of embellishment and the agent of aesthetic play.”

In between those two extremes in time and material are several examples of lavishly illustrated Qur’ans, the Islamic sacred book, by artisans in Siyu in present day northern Kenya, and the artful scholarly inscriptions in a 19th century volume of Arabic grammar.

But words were also found slipped inside the amulet cases from the Kenyan town of Lamu, adorned with words and meant to encase written notes and invocations. Arabic calligraphy elegantly rings porcelain wedding bowls from the 19th century. In Swahili culture, “words are not merely visual things,” Purpura says. “Words are also sonorous. Words are to be recited. Words are visually interesting and compelling, and words themselves also embody piety and acts of devotion.”

This is especially true in the kanga, the popular African wraps of the region that often have written invocations accompanying their design. The fashionable women of the Swahili Coast demanded the most up-to-date phrases on their garments, something that frustrated European manufacturers who couldn’t get the new designs to them fast enough before another was adopted.

As depicted in a series of photographs on display from the late 19th century, women wearing kangas with Arabic to Latin script began wearing Swahili phrases. “The saying was very important,” Purpura says. “It had to be a very funny, ribald, poetic or a devoted saying. So, there would be change in what kind of saying would be written.” And women often had hundreds of kangas in order to keep up with the changes, she says.

Gus Casely-Hayford, the newly installed director of the National Museum of African Art, said he was glad the show expands the notion of what constitutes African art. “As the stunning and surprising works on view in this exhibition reveal, the seemingly rigid frontiers that have come to define places like Africa and Asia are in fact remarkably fluid, connected through the intersections of art, commerce and culture.”

Appropriately, the World on the Horizon exhibition is on view in a underground gallery adjacent to Asian art from the collections of the nearby Freer and Sackler Galleries, just as the Swahili Coast found itself an artistic conduit of mainland Africa with India and China across the Indian Ocean.

“It’s perfect that it acts as this intersectionality between the major Asian collections on this side and moves into the major African collections on the other side,” says Meier.

"World on the Horizon: Swahili Arts Across the Ocean" continues through September 3 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/35/c9/35c9c42a-945e-4cc8-9e08-e6589462b426/17geary_157_tanzania.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)