In the Footsteps of Three Modern American Prima Ballerinas

A new exhibition shows that classical ballet and the role of the ballerina are rapidly changing

For more than a century, dance has reflected important moments in the nation’s history. Isadora Duncan swirled onstage in 1900 as an independent “New Woman;” choreographer Busby Berkeley gave Depression-era audiences a welcome escape by filling movie screens with dance spectacles, and during the Cold War, Soviet dancers like Mikhail Baryshnikov fled to the United States in search of artistic freedom and creative opportunity.

A fascinating new exhibition, “American Ballet,” exploring dance is currently on view at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. The new display case show tells the story of three modern prima ballerinas who have dazzled audiences from stage to screen and from Broadway to the White House.

In the modern era, dance reflects the disruptions of cultural transformation. “Ballet today has absorbed the cacophony of social, political and cultural influences that reverberate in our lives,” says curator Melodie Sweeney. “As a result, classical ballet and the role of the ballerina are both rapidly changing.”

American popular dance first stepped to the music of Irving Berlin, George M. Cohan, and Sissle and Blake on the vaudeville stage. But an American style of ballet was slower to emerge.

A European performance art, ballet never found its unique New World footing until Russian-born and classically trained George Balanchine immigrated to the U.S. in 1933. Although he earned immediate success choreographing for Hollywood and Broadway, his biggest impact came from inventing American ballet. He organized the New York City Ballet in 1948, and his 150 works of choreography for that company established a uniquely American style: Balanchine’s ballet soared.

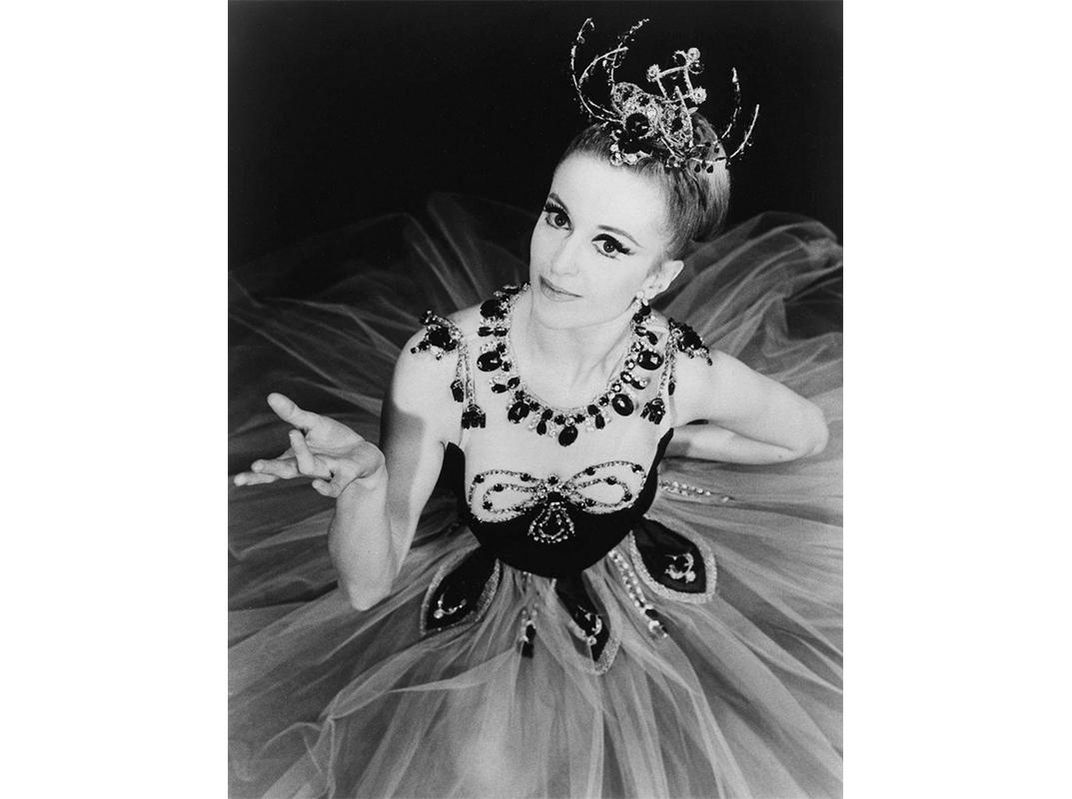

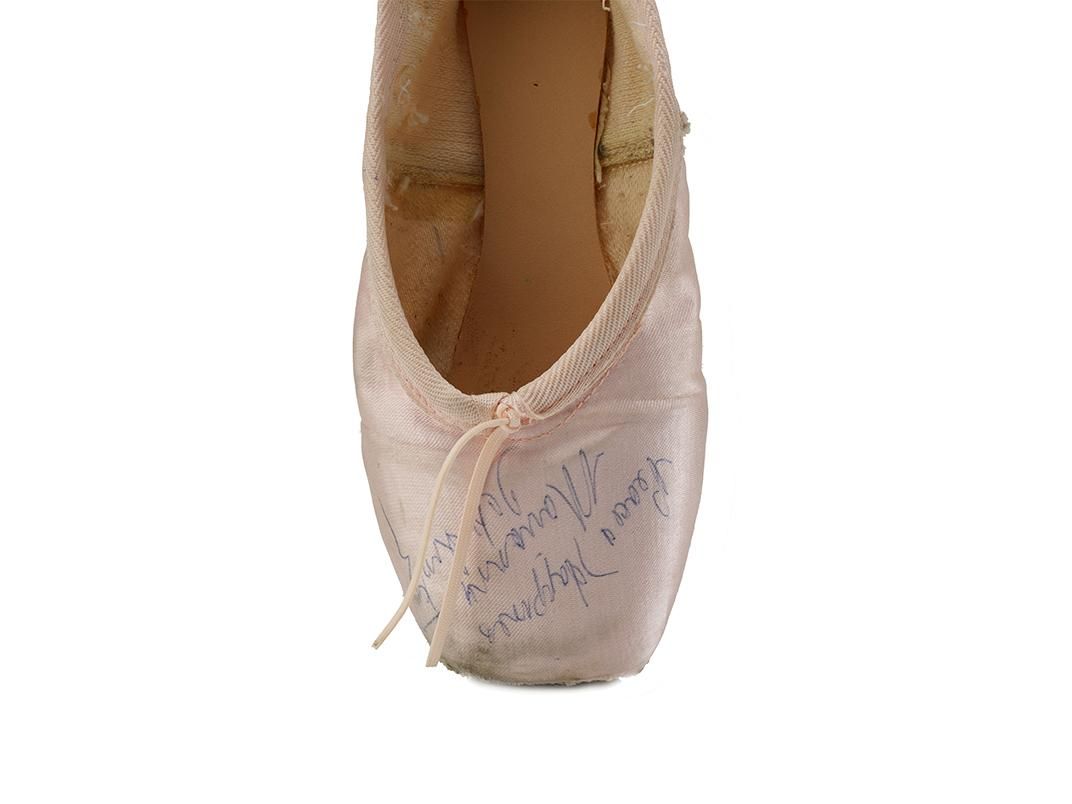

Every choreographer needs a muse, and one of Balanchine’s chief inspirations, Violette Verdy, is spotlighted in the American Ballet exhibit. Verdy was born in France and established an important postwar career in Europe, including a starring role in the 1949 German film Ballerina. After she immigrated to the U.S., she became one of Balanchine’s “muses” between 1958 and 1977. He choreographed leading roles for her in several of his works, most importantly in Emeralds, which was the opening ballet of his triptych Jewels, and in Tchaikovsky’s Pas de Deux. This exhibit features Verdy’s “Romantique” tutu from the Pas de Deux that she performed for President and Mrs. Gerald Ford at the White House in 1975. The costume was designed by Barbara Balinska, costumer for the NYCB and earlier for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. A pair of Verdy’s pink satin ballet shoes from the film Ballerina is also displayed.

Marianna Tcherkassky was born in Maryland and is of Russian and Japanese descent. She studied at Mary Day’s Academy of the Washington School of Ballet, and joined the American Ballet Theatre in 1970, becoming a principal dancer in 1976. She made her debut with Baryshnikov and earned recognition as one of the world’s leading ballerinas. Known best for her performance as Giselle, she won accolades from New York Times dance critic Anna Kisselgoff, who called her “one of the greatest Giselles that American ballet produced.”

The exhibit features her Giselle costume from her performance with Baryshnikov in the American Ballet Theatre production. The costume was made by May Ishimoto, a Japanese American who was one of this country’s leading ballet wardrobe mistresses.

Although dance in general has reflected the diversity of the national experience, ballet has remained the aloof exception to this art’s inclusiveness. Most American ballet companies have adhered to a classical tradition that is very European and very white.

Misty Copeland is changing that. Raised in difficult circumstances, she only discovered ballet at the age of 13. But her talent was so remarkable that she joined the American Ballet Theatre in 2001, and in 2015 became the first African-American female to be named “principal.” Now this groundbreaking ballerina is determined to fling open ballet’s doors to young African-American dancers. She sees dance as “a language and a culture that people from everywhere, all over the world, can relate to and understand and come together for.”

Choreographer Dana Tai Soon Burgess, whose troupe is officially “In Residence” at the National Portrait Gallery, calls Copeland the dance world’s “new muse.” Balanchine’s 20th-century “muse” represented an elongated female archetype, while Burgess explains that Copeland combines artistic excellence with “an athletic prowess that expands the ballet vocabulary and demands a choreography that pushes American ideals to new heights.” For Burgess, such a muse “completely changes how a choreographer works.”

In addition to her work with ABT, Misty Copeland has appeared as “the ballerina” in Prince’s video Crimson and Clover (2009), and as Ivy Smith (“Miss Turnstiles”) in a 2015 Broadway production of On the Town. Her costume from On the Town, including the headdress and tiara, is displayed in exhibit.

The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts has invited Copeland to “curate” a program this April for Ballet Across America, a series that celebrates “innovation and diversity in American ballet.” As Burgess explains, “Misty is redefining who the American ballerina is: she is our new ‘Lady Liberty’—a strong woman who embodies the spirit of America today.”

"American Ballet" will be at the National Museum of American History indefinitely. "Ballet Across America—curated by Misty Copeland and Justin Peck program at the Kennedy Center is April 17 through April 23, 2017)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Amy_Henderson_NPG1401.jpg)