Forty Years Later, the Voyager Spacecraft Remain Beacons of Human Imagination

Remembering the mission that opened Earth’s eyes to the vastness and wonder of space

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7d/a9/7da980ed-300c-42d8-be66-90b028fe590e/voyagerpic1.jpg)

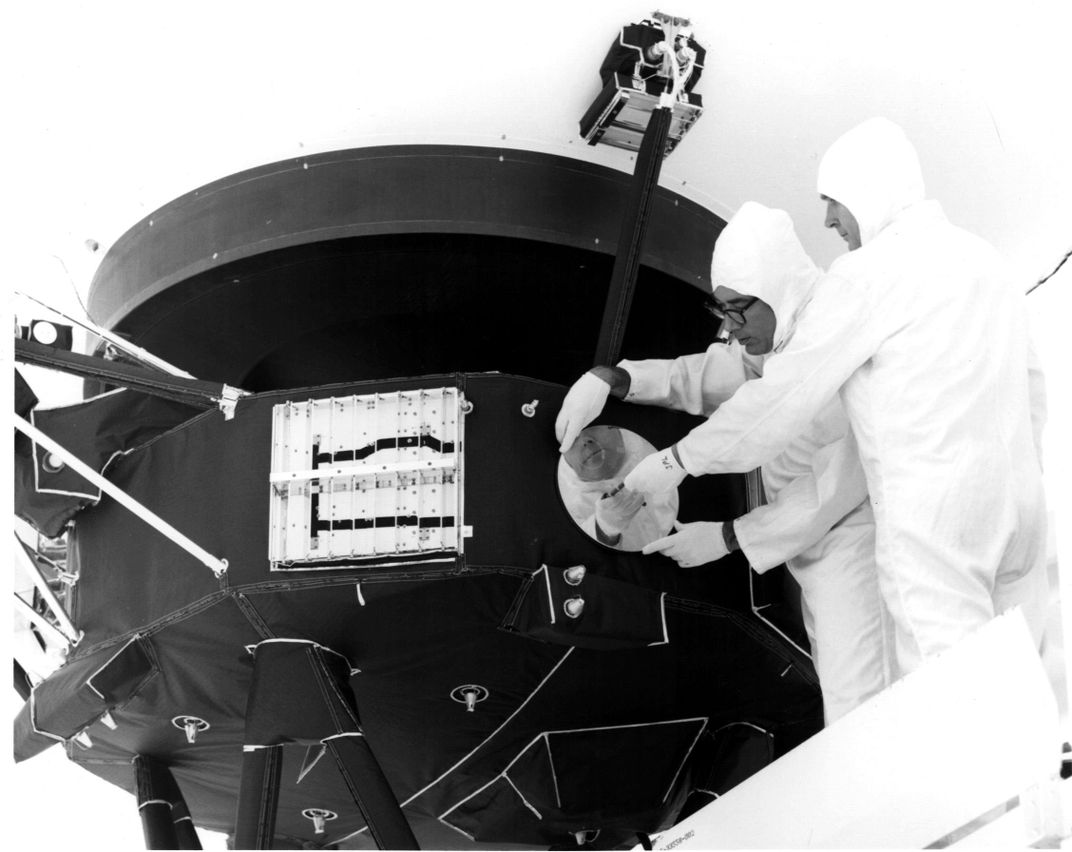

The sky in Cape Canaveral was a wan blue-gray on the morning of August 20, 1977, and an eerie stillness hung over the warm waters of the Atlantic Ocean. The quiet was broken at 10:29 a.m. local time, when the twin boosters of a Titan III-Centaur launch system roared to life on the launch pad, lifting from Earth’s surface NASA’s Voyager II spacecraft, assembled painstakingly in the clean rooms of California’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and bound on an interplanetary odyssey of unprecedented proportions.

Voyager II’s primary targets, like those of its twin, Voyager I, were the gas giants Jupiter and Saturn. Since Voyager II’s trajectory was less direct, Voyager I—true to its name—arrived at Jupiter first, despite having departed Earth more than two weeks later than its counterpart, on September 5.

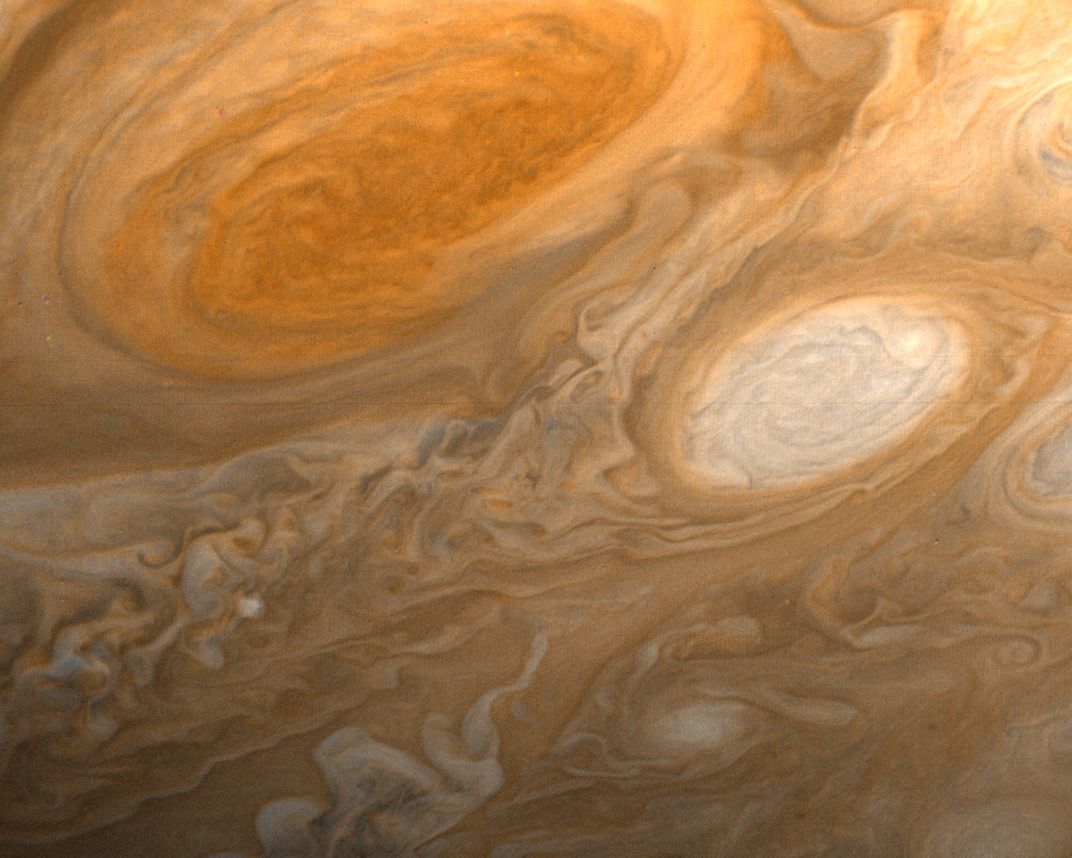

Both equipped with a battery of tools including standard cameras, infrared and ultraviolet imagers, magnetometers and plasma sensors, the Voyager spacecraft arrived at their destination in 1979, nearly two years after they set out. With stunning thoroughness, the two vehicles surveyed Jupiter (including its famous Great Red Spot), Saturn (including its dusty, icy rings), and the pair’s myriad moons, generating numerical data still instrumental today and capturing high-resolution photos of faraway worlds that could previously only be dreamed of.

Built to last five years, the Voyagers have proved far more durable than anyone bargained for in the 1970s. After fulfilling their principal mandate of Saturnian and Jovian reconnaissance, the two vessels continued on, hurtling towards the edge of our solar system at more than 35,000 miles per hour. Voyager I, now some 13 billion miles from the Sun, has officially broken free. Voyager II, not far behind (in relative terms, anyway), is fast approaching the milestone itself—and it managed to acquire data on Neptune, Uranus and their satellites along the way.

Solar cells would be useless at such a tremendous range; fortunately, the unmanned spacecraft are powered by radioactive hunks of plutonium, which by their nature continuously give off heat. And though the Voyagers transmit data with a paltry 20 watts of power—about the equivalent of a refrigerator light bulb—the miraculous sensitivity of NASA’s Deep Space Network radio dishes means that new information is to this day being received on Earth. Intended to gauge solar wind, Voyager technology can now provide measurements on interstellar wind, a possibility that would have sounded ludicrous at the time the pair was launched.

To celebrate this crowning achievement of modern science, and the 40th anniversary of the journey’s commencement, the National Air and Space Museum will be hosting a public event Tuesday, September 5, beginning at 12:30 p.m. A panel discussion and series of distinguished speakers will address the enduring practical and humanistic significance of the Voyager mission.

“Voyager can only be described as epic,” says museum curator Matt Shindell, who will be emceeing the festivities. “The scientists who imagined it knew that a ‘grand tour’ of the outer solar system was a mission that”—due to the constraints of celestial mechanics—“could only be undertaken once every 175 years. If they didn’t accomplish it, it would be up to their great-grandchildren to take advantage of the next planetary alignment.”

Shindell stresses that the painstaking calculations needed to coordinate Voyager’s series of gravitational slingshot maneuvers were done on computers that by today’s standards seem laughably obsolete. The person-hours put in were staggering. “And,” he adds, “the planetary scientists who worked on Voyager dedicated more than a decade of their careers to getting the most robust datasets possible from the brief flyby windows at each planet.”

The dedication and sacrifice needed to make the Voyager concept a reality can hardly be overstated. “The scientists, engineers and project managers involved in Voyager dreamed big and accomplished the improbable,” Shindell says. “This is worth celebrating.”

A NASA development test model of the Voyager spacecraft looms large in the Air and Space Museum’s Exploring the Planets gallery. A silent testament to the power of human imagination, the model will overlook the anniversary gathering.

“I’d say it is the signature artifact” of the space, Shindell says, “suspended almost in the center, with its impressive magnetometer boom stretching across nearly the entire gallery, and with the cover of its famous golden record displayed below it.”

The content of the Voyager Golden Record, intended to present a microcosm of human culture to any extraterrestrial beings who might one day intercept it, was decided on by a panel of scientific thinkers headed up by Cornell’s beloved Carl Sagan. Two copies were pressed, one to be flown on each of the Voyager spacecraft. The music etched into the disc ranges from Bach to Chuck Berry; it is complemented by a selection of natural sounds, such as rainfall and water lapping a shore. Visual materials accompanying the record highlight scientific knowledge.

Voyager paved the way for countless follow-up missions, and ignited popular interest in such disparate and fascinating locales as Jupiter’s moon Europa (which features a water ice crust, and possibly a subsurface ocean), Saturn’s moon Titan (where a “methane cycle” has been found to exist in place of Earth’s “water cycle”), and Uranus’s moon Miranda (whose fault canyons are as deep as 12 miles). More than anything, Voyager serves as a constant reminder of the majesty and diversity of the cosmos, and how vanishingly minute the beautiful planet we call home truly is.

In February of 1990, the Voyager 1 probe rotated its camera to capture a composite photo of Earth at a distance of 3.7 billion miles. Christened “Pale Blue Dot” by Carl Sagan, who had requested that it be taken, the picture is a humbling portrayal of Earth, which appears as a solitary speck in a sea of cosmic black.

On that speck, Sagan writes, “everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives.” In his eyes, the message of Voyager is crystal-clear. “There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we’ve ever known.”

The National Air and Space Museum will be holding a commemorative gathering on Tuesday, September 5. Festivities, including a panel discussion and lectures from several distinguished speakers, will begin at 12:30 p.m.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSC_02399_copy.jpg)