Four Craft Artists Use Their Medium to Tell the Story of Our Times

The Renwick’s newest show challenges everything you thought you knew about craft art

When Smithsonian curator Abraham Thomas realized that the 2018 Renwick Invitational would open just after the midterm elections, he knew that he wanted the juried exhibition to be about more than just the showcasing of midcareer and emerging artists. He felt that it should say something about the times—and the four artists selected for “Disrupting Craft,” on view through May 2019, make big statements about where we stand.

Thomas, along with independent curator Sarah Archer and Annie Carlano, a senior curator at the Mint Museum, chose the artists in large part because of their political activism and focus on community engagement. The Renwick Gallery, Thomas says, is the perfect setting to encourage visitors to delve into some of the great debates of the moment.

The Smithsonian’s museums “are important civic spaces where we should be able to create a safe environment where we can have different conversations,” says Thomas. He’s hoping the show engages with audiences over “the questions it raises about immigration or about complex cultural identity.”

A mass of disembodied ceramic human heads randomly piled onto the floor in the first gallery provides one jarring example. The viewer is confronted by the bald figures, all with a slightly different physiognomy and in the different shades of human skin—brown and black, and occasionally, white. The assemblage by ceramicist Sharif Bey, titled Assimilation? Destruction? is primarily about globalization and cultural identity. It is also a reference to Bey’s identity as a potter and an artist of color.

The piece is never the same in any exhibition—the 1,000 or so pinch pot heads are brought to a gallery in garbage cans and “unceremoniously dumped out,” says Bey, showing a video of the process. The heads break, crack and get pounded into smaller shards. Over time, he says, the piece, which he created for his MFA thesis project in 2000, will become sand. Ultimately, Assimilation? Destruction? signifies that “you’re everything and you’re nothing at the same time.” With its shifting collective and individual shapes, the assemblage is also “a comment on what it means to be a transient person,” he says.

Bey, 44, has had his own migrations—out of a Pittsburgh working-class neighborhood into that city’s artistic incubators, taking classes at the Carnegie Museum of Art, and being selected for a prestigious after-school apprenticeship at the Manchester Craftsmen’s Guild. It signaled a new and perhaps previously unconsidered career path for a kid with 11 siblings in an industrial town. Currently a dual professor at Syracuse University’s College of Arts and School of Education, he has never lost touch with his first love—making functional pots, some of which are included in the Renwick show.

“We all have histories as makers,” says Bey. “My orientation is the vessel,” he says, adding that for as long as he can remember, working with clay has been therapeutic. He often works in his living room while watching over his children—it helps him evade the guilt he feels when in the studio, which his wife says is like his own little vacation, he says with a laugh.

Tanya Aguiñiga, 40, has also used her art to examine her history. As a Mexican-American, born in San Diego, who grew up in Mexico within shouting distance of the U.S. border, she is an unapologetic and energetic activist—a feature nurtured by her experience working in the Border Art Workshop/Taller de Arte Fronterizo when she was a 19-year-old college student. After earning her MFA in furniture design from Rhode Island School of Design, Aguiñiga missed her homeland. A United States Artists Target Fellowship in 2010 gave her the freedom to go back and learn weaving and embroidery from indigenous craftsmen.

Her latest piece, Quipu Fronterizo/Border Quipu evolved from her project, AMBOS—Art Made Between Opposite Sides, and a play on words—ambos means “both of us” in Spanish—and is an artistic collaborative along the border. Quipu signifies a pre-Columbian Andean organizational system of recording history. Aguiñiga began her Quipu at the San Ysidro crossing in Tijuana in August 2016—after presidential candidate Donald Trump’s derogatory statements about Mexicans.

She and AMBOS team members circulated among mostly Mexicans waiting to cross to the United States, or who lived or worked nearby and asked them to take two strands of colorful stretchy rayon fabric to tie knots in a kind of reflection on the relationship between the two countries, and to respond to a postcard that asked: ¿Qué piensas cuando cruzas esta frontera? / What are your thoughts when you cross this border?

The artist had her own feelings about the border—which she crossed each day to go to school in San Diego, where she was born, and where her grandmother watched over her while her parents worked in the city. In creating the Quipu, says Aguiñiga, “I thought about how many of us make that commute every day, and how it’s so stigmatizing.” The wait for crossings is long and Mexicans are exhaustively questioned before they are permitted to enter the U.S. “It’s this really weird thing where you feel like you’re doing something wrong even though you’re not,”Aguiñiga says.

“I wanted to get a gauge on what people were feeling because there was so much hate being thrown our way,” says Aguiñiga, who published the postcards on a website. The knotted strands were collected from the commuters and displayed on a billboard at the border crossing. The assemblage of knots—tied together into long strands—and postcards, are both meditative and moving. One postcard response channeled Aguiñiga’s thoughts: “Two indivisible countries forever tied as 1.”

Aguiñiga has since recreated the Quipu project at border crossings along the length of the border. “For the most part, the U.S. thinks about the border as this really separate place, black and white, and it’s not. It’s like one family going back and forth,” Aguiniga says.

Stephanie Syjuco, 44, born in the Philippines, also punctures perceptions about culture and “types,” often using digital technology to comment, somewhat cheekily, on how viewers take computer-generated images to be “real.” The University of California, Berkeley assistant professor of sculpture is not a traditional craft artist, but was chosen, says curator Thomas, for “the way that the artist takes the conceptual toolkit of craft and uses it to interrogate those issues around cultural identity and cultural history.”

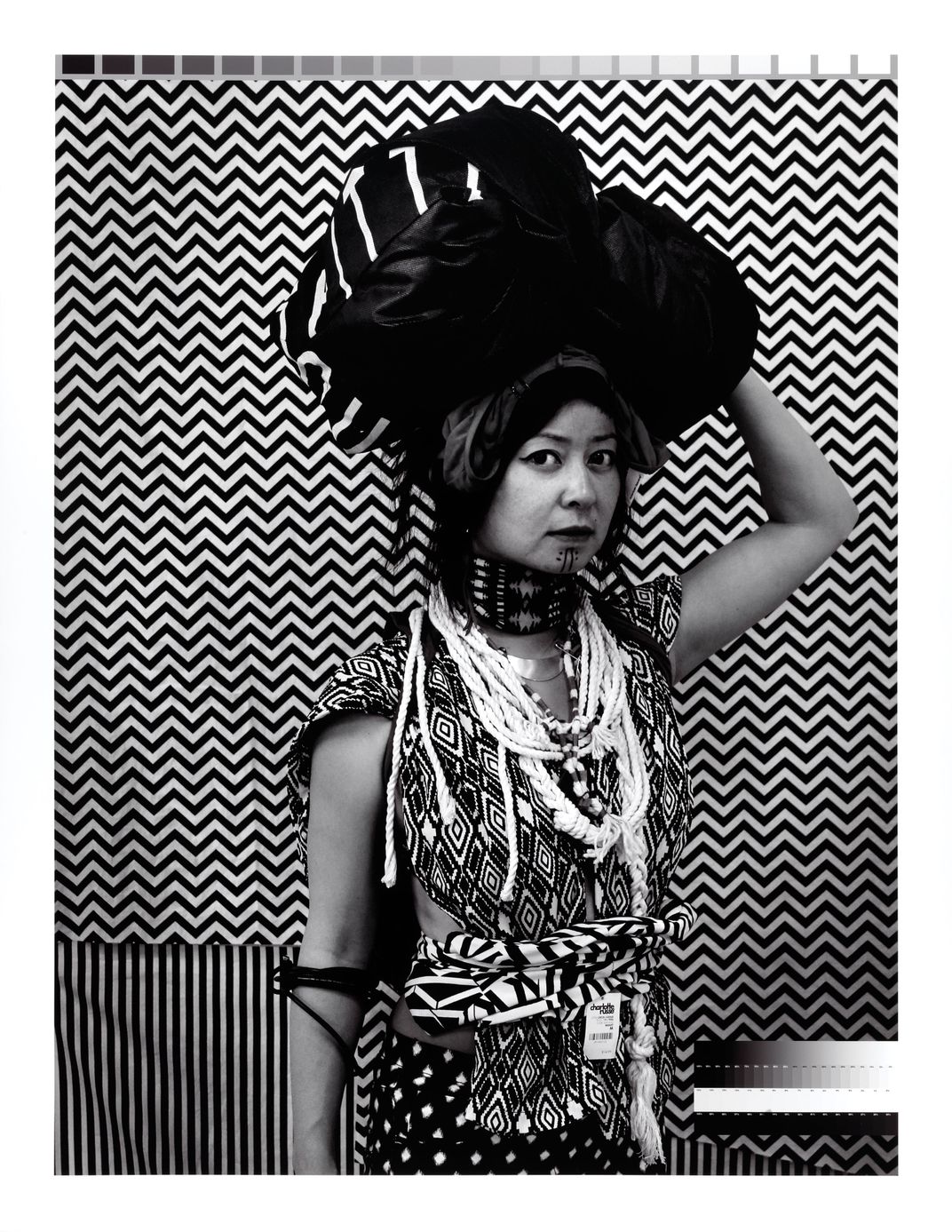

Syjuco pokes fun at how the West views and consumes ethnicity in Cargo Cults: Head Bundle and Cargo Cults: Java Bunny. In the two black and white photographs, Syjuco, as the subject, is dressed in a variety of “ethnic”-looking patterned fabrics, and elaborate “jewelry.” The ethnic fabrics are fictional—often digitized mimicry. The fabrics were purchased at mall retailers and one of the “bracelets” around her arms is a cord bought at an electronics shop. In Java Bunny, Syjuco is posed against various black and white patterned fabrics, but a “Gap” tag is visible. The artist says she was inspired by a graphic technique—dazzle camoflauge— used on battleships in World War I to confuse enemy gunners.

“They’re a projection of what foreign culture is supposed to look like,” she says—just like ethnographic images from the 19th century. Those images often represented “true” natives, but the notion of “native,” isn’t straightforward. The idea of authenticity “is always in flux,” Syjuco says. The Philippines, for instance, is a hybrid of its colonizers: Spain, Japan and America. “I’m not saying all culture is made up. It’s just that there’s a lens through which culture is filtered, so the viewer is narrating a lot.”

Dustin Farnsworth, 35, has also recently begun focusing on cultural stereotypes. The artist spent some of his early career examining the impact of the decline of industry and recession on his native Michigan.

He constructed massive architectural pieces that teetered on top of sculpted mannequin-like heads of young people. The effect was to vividly convey the weighty consequences of industrial and civilizational decline on the generations to come. Several are featured in the Renwick show.

But a 2015 artist residency in Madison, Wisconsin, changed his focus. He arrived soon after the police shooting of the unarmed 19-year-old, African-American Tony Robinson. Then, in 2016, while he was in a similar visiting artist residency in Charlotte, North Carolina, police killed Keith Lamont Scott, also a black man. Both shootings intensely reverberated in the communities.

“It felt like that was so much more important than the things I was inventing and projecting,” says Farnsworth, sporting a trucker hat with “Dismantle White Supremacy” emblazoned on the front.

Shortly after those residencies, he created WAKE. With its diagonal black stripes that reference the U.S. flag, it features dozens of skull-like masks sculpted out of Aqua-Resin displayed in repeating rows over a white background. It was Farnsworth’s powerful response to the numbing effect of multiple school shootings. WAKE, he says, recalls the word’s multiple definitions and usages—it can be a vigil for the dead or to rise out of slumber; and the phrase, “woke,” is a term used in social justice circles meaning to be aware, a usage that grew out of the Black Lives Matter movement.

Farnsworth has collaborated with sign painter Timothy Maddox to create WAKE II, a massive 9.5- by 26-foot piece in the Renwick show. The skull-death masks return, with hundreds set on a colorful background of overlapping sloganeers’ banners: “Dismantle White Supremacy;” “No Justice No Peace;” and, “No racist police,” among them. The immense size of the piece is no accident.

“I’m very interested in memorial,” Farnsworth says. WAKE II was also meant to be in-your-face—a way to stir the pot about police shootings and social justice. “A lot of us kick it under the carpet,” he says.

He’s now moving away from the dead and towards elevating the living. The Reconstruction of Saints is his first attempt. It is his David, aimed at confronting the Goliaths of Confederate monuments, says Farnsworth. The heroic bronze-like bust of an African-American boy reflecting skyward is his attempt to sanctify minority youth, Farnsworth says.

Reactions to Saints when it was in progress—mostly in the Carolinas—was distressingly bigoted, he says. That attitude “is something that needs to be confronted, and I’m still figuring out the best way to do that,” says Farnsworth.

Thomas says he and his fellow curators chose Farnsworth and the other three artists in large part because of their willingness to confront established attitudes and conventions.

“The work featured here offers us moments of contemplation on the rapidly transforming world around us, and disrupts the status quo to bring us together, alter our perspectives, and lead us to a more empathetic, compassionate future,” he says.

"Disrupting Craft: Renwick Invitational 2018," curated by Abraham Thomas, Sarah Archer and Annie Carlano, is on view through May 5, 2019 at the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Renwick Gallery, located at Pennsylvania Avenue at 17th Street NW in Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/7f/4c/7f4cdc38-109e-4d0a-ac8a-d023478ee923/artist_portrait_bey.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/72/03/72031a77-4fe1-4720-97a5-585bc581ee51/artist_portrait_farnsworth.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)