Frederick Douglass’ 200th Birthday Invites Remembrance and Reflection

This Douglass Day, celebrate an icon’s bicentennial while helping to transcribe the nation’s black history

:focal(2998x1766:2999x1767)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/a1/77/a17766d7-a1fe-4d6a-8417-d4e9de67b388/2013_239_10_001.jpg)

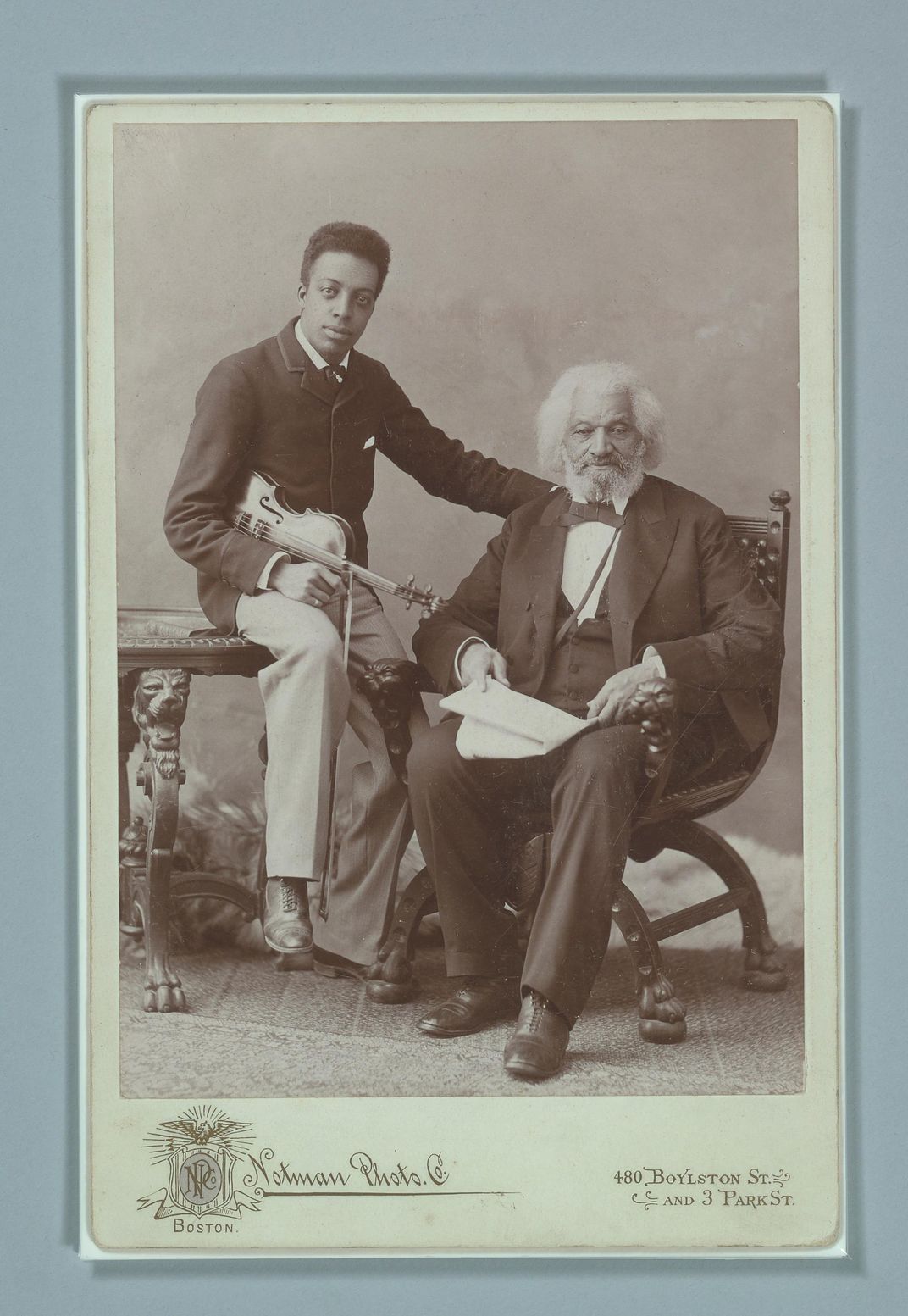

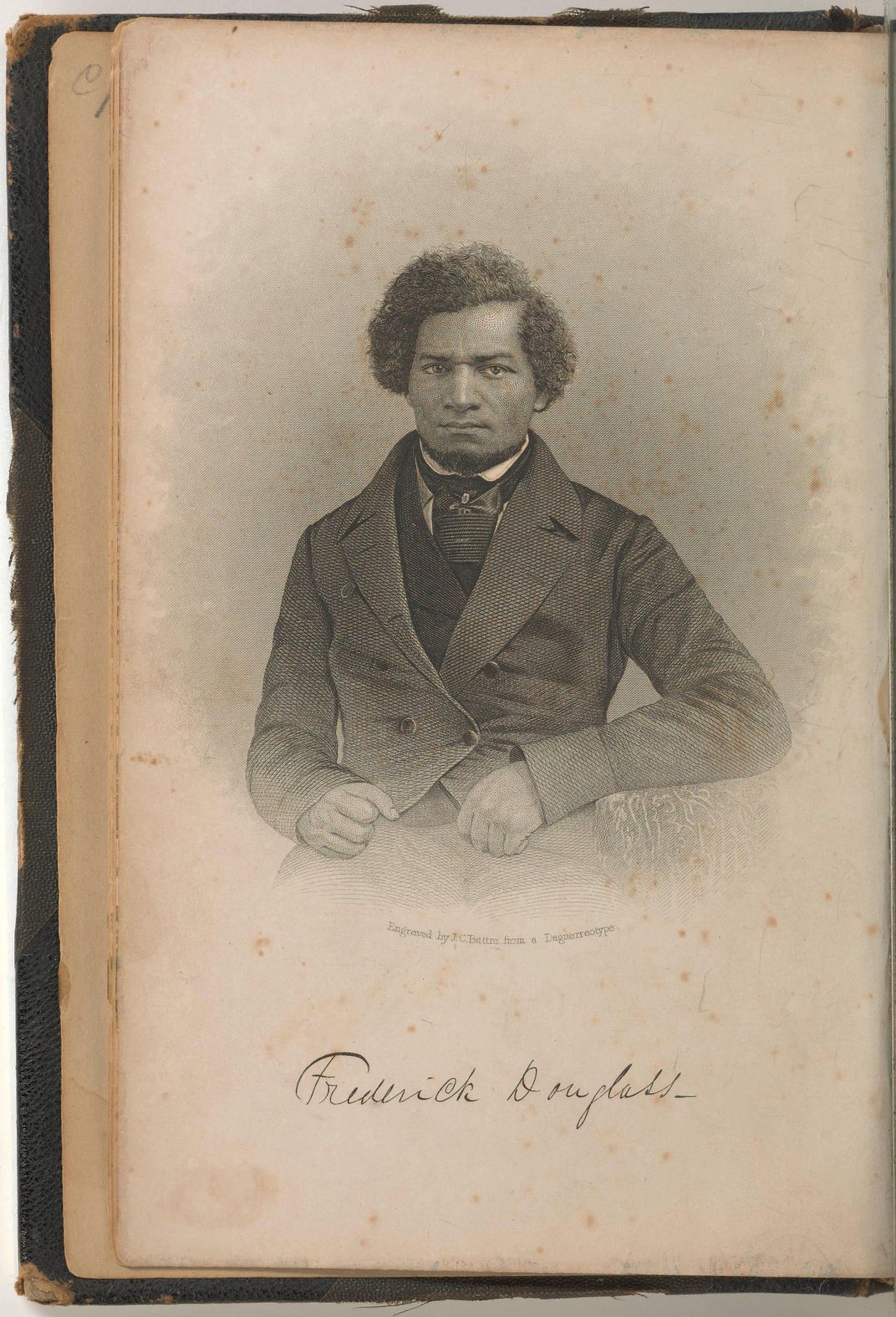

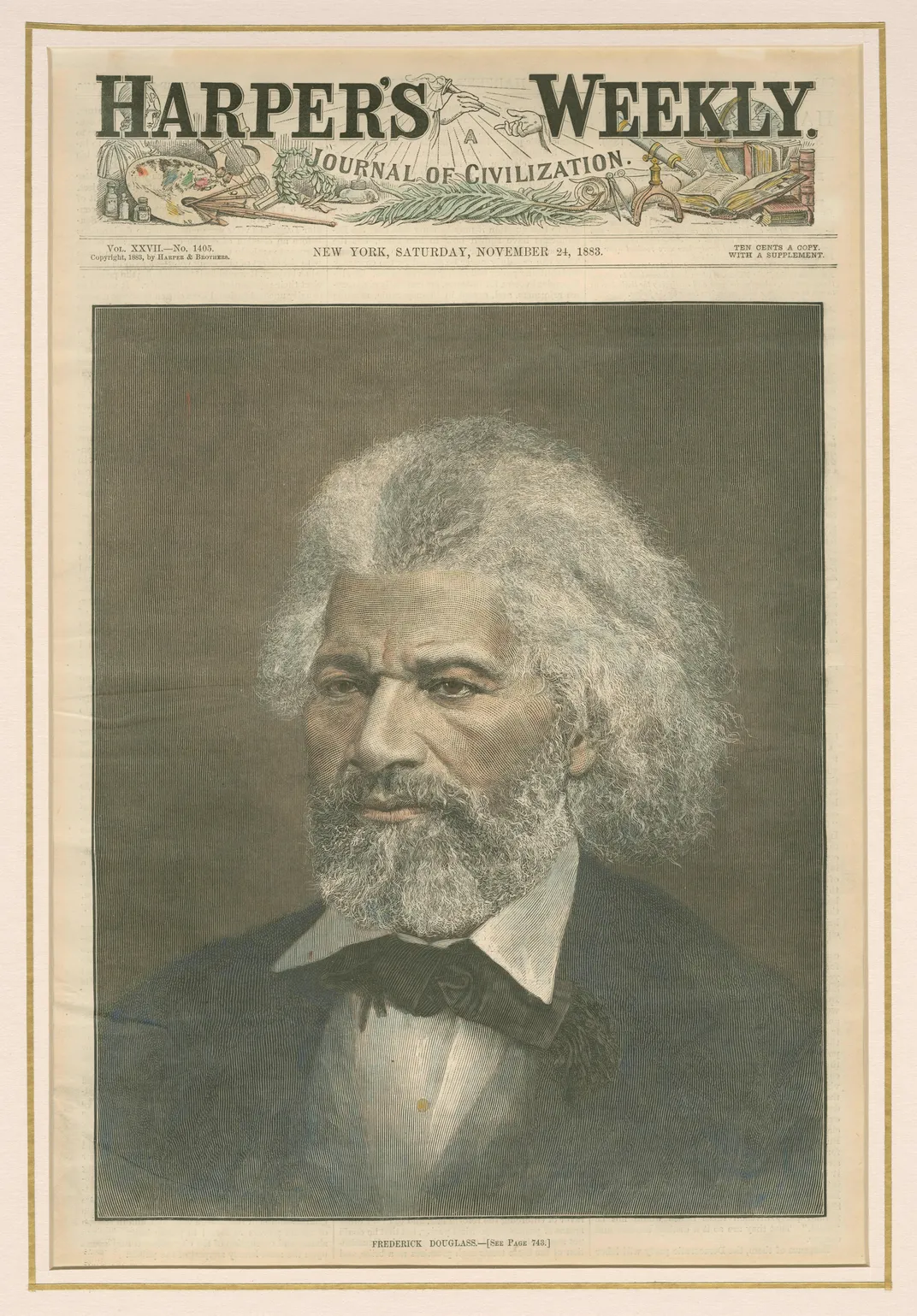

In pictures, the eyes of Frederick Douglass, the iconic enslaved man who escaped and became an international abolitionist and activist, blaze from a stern face, framed by a lion’s mane of kinky hair. Douglass (1818-1895) once said: “I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.”

This month, the nation prepares to celebrate the 200th birthday of this man, whose eloquent advocacy of freedom and equality for blacks and women continues to resonate as Americans navigate a society still roiled by racial tensions in 2018.

“It unfortunately seems very familiar when we read about a lot of the history that Frederick Douglass was involved in,” says Jim Casey, co-director of the Colored Conventions Project (CCP). The group got its start in 2012 in a University of Delaware graduate class taught by P. Gabrielle Foreman. Fascinated by the black political conventions that began in 1830 and continued until the turn of the century, faculty, students and librarians came together to bring "buried African American history to digital life."

Free African-Americans held some 400 state and national conventions to strategize on how to achieve justice, education and equal rights through the 1920s. Casey explains that one of the reasons the CCP became interested in Douglass is that it found evidence that he attended the conventions for some 40 years, from 1843 through 1883. That’s a time period that included some of the nation’s most contentious history, dating from before the Civil War and including the struggles that followed for many years afterwards, and which arguably persist to this day.

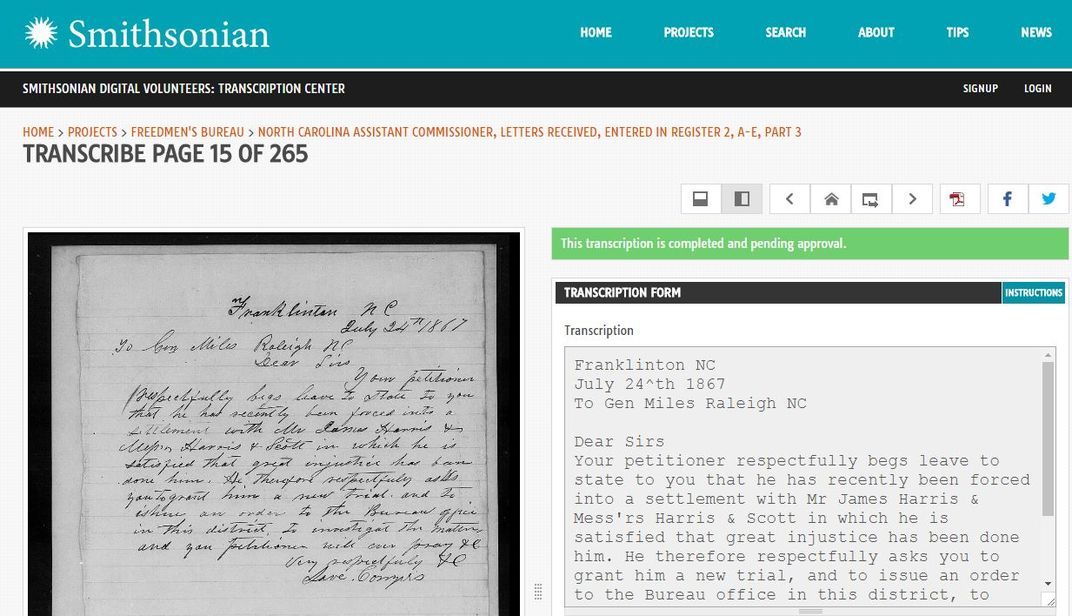

This year, CCP is partnering with the Smithsonian Institution Transcription Center and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture to celebrate Douglass’ bicentennial. The event features an online transcribe-a-thon, a crowdsourcing effort that invites participants to log in and transcribe the recently digitized papers from the U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau.

The museum has been working to make it easier for scholars and visitors to find out more about their family history and the post-Civil War era. There will be a live streaming on Facebook and Twitter where Smithsonian experts will be chatting with participants. From noon until 3 p.m. on February 14, there will be simultaneous celebrations (including birthday cake) at some 30 schools and other venues, at which an actor will perform part of the speech Douglass gave in 1876 at the dedication of the Freedmen’s Monument in Lincoln Park in Washington, D.C.

“This year, we’ve really been struck by how much people are investing in engaging with the historical examples of these debates in ways that remind us that the history of Frederick Douglass and the Colored Conventions and the Freedmen’s Bureau is not something that distant or abstract anymore,” Casey says. “It’s something that’s showing up on the front pages every day.”

The organization, with the public’s help, has nearly finished transcribing the minutes it has found so far from the National Conventions of Free People of Color. Nineteenth-century blacks discussed the need for community-based action to raise money, establish schools and literary societies and began organizing a civil and human rights campaign. This was at a time when the rights of African- Americans, free or not, were curtailed. Many thought the doors of democracy would open at the end of the Civil War, only to have them slammed in their faces. Anti-black race riots became commonplace, and the seeds of modern-day racial violence were sown.

“Finding those similarities again and again is a way of thinking through some of the problems that we have today,” Casey says. “At the end of many of the conventions they would print minutes and proceedings, often recording who was there and what they said, but they were always carefully edited about how they were going to present their group to the larger world.

Frederick Douglass was born into slavery on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in 1818 and named Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey. He became one of the most famous black men in the nation during a life where he consistently fought for human rights. Hired out to work in Baltimore, he taught himself to read and write, and escaped slavery in 1838 with the help of a free black woman who later became his wife. He changed his last name to Douglass after they moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts. As an orator, he traveled around the country to speak about his experience as a slave. In 1845, he published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass; required reading in many black studies classes. Abolitionists officially purchased his freedom after he spent time traveling overseas giving lectures.

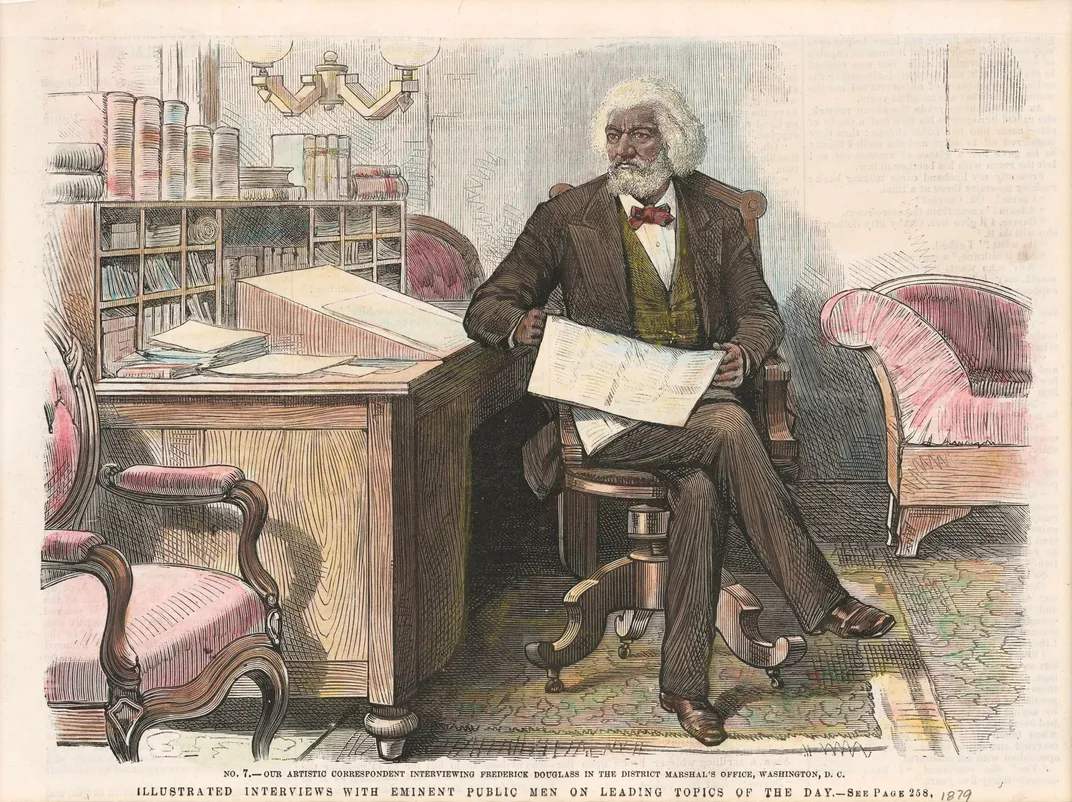

Douglass’ battle for human rights led to his involvement with the women’s rights movement and the Underground Railroad. As the nation became embroiled in the Civil War, he advised President Abraham Lincoln on the fate of former slaves, and later met with President Andrew Johnson on the subject of black suffrage. After moving to Washington, DC in 1872, Douglass held a string of high-profile positions. He served as president of the Freedmen’s Bank prior to its 1874 closure, and received prestigious federal appointments under five separate presidents of the United States.

Douglass kept up a rigorous speaking schedule, battling against the continued injustice and basic lack of freedom faced by many Americans. He became not only the first African-American to be confirmed for a presidential appointment in 1877, but also the first black man nominated to be vice president of the United States.

“If there is no struggle there is no progress. … Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did, and it never will,” Douglass once said.

Last year, partly because of Douglass’ long history of involvement with the Colored Conventions, CCP revived Douglass Day, a celebration of Frederick Douglass’ birthday. Douglass didn’t know his exact birth date, but he chose to celebrate on February 14th. Casey says Douglass Day became a holiday in black communities following his death in 1895; citizens endeavored to remember his words as they protested against racial violence.

“There are a number of people who lobbied to make his birthday into an annual holiday, including notable activists such as Mary Church Terrell and even Booker T. Washington, who in a kind of 19th- early 20th-century crowdsourcing starts to contact people on the occasion of Douglass’ birthday,” Casey explains, adding that there were Douglass Day celebrations up through the 1940s. “I found evidence of Douglass Day celebrations in dozens of cities across the U.S. It was a day when they could get schoolchildren out of school for the day and they would read speeches and hear about the life of Douglass. They would speak out for civil rights and against lynchings in the south.”

A major part of this year’s celebration is the Smithsonian’s transcribe-a-thon, where participants are being invited to help transcribe the U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau Papers as part of African American History Museum’s Freedmen’s Bureau Transcription Project. “So this is one of those collaborations where we’re both going to benefit down the road,” explains the museum’s genealogist Hollis Gentry, standing in the Robert Frederick Smith Explore Your Family History Center. It is a room at the museum that looks like a library, with several computers where visitors can receive guidance on researching their family history and conducting oral interviews. There’s also instruction on learning how to preserve your own family films and photographs. An interactive digital experience, Transitions in Freedom: The Syphax Family, guides viewers through the history of African-American families from slavery to freedom through archival documents, maps and other records.

“Down the road,” says Gentry, “we’ll be able to chart some of the careers of the individuals who were participating in the Colored Conventions. We can begin to document their origins or their rise to power and prominence through the [Freedmen’s] bureau. . . . You know there are scholars who’ve been arguing over the meaning of Reconstruction, so we’re going to give them a new set of data to examine. It’s going to take a while to go through.”

Part of the reason for that is the anachronistic terminology that abounds in the Freedmen’s Bureau records. There were different names for food used then, such as maize instead of corn. Animal parts were called different things, as were articles of clothing such as pantaloons—known now of course as trousers or pants. Abbreviations weren’t the same as they are in the 21st century either, and then there’s that pesky cursive writing to decipher.

At the Family Center, experts are talking about the possibility of creating a sort of thesaurus for the Freedmen’s Bureau papers to make it easier for visitors or those helping to transcribe them find their way through the antiquated documents. The records will be a huge boon for an audience that will include amateur genealogists and scholars alike.

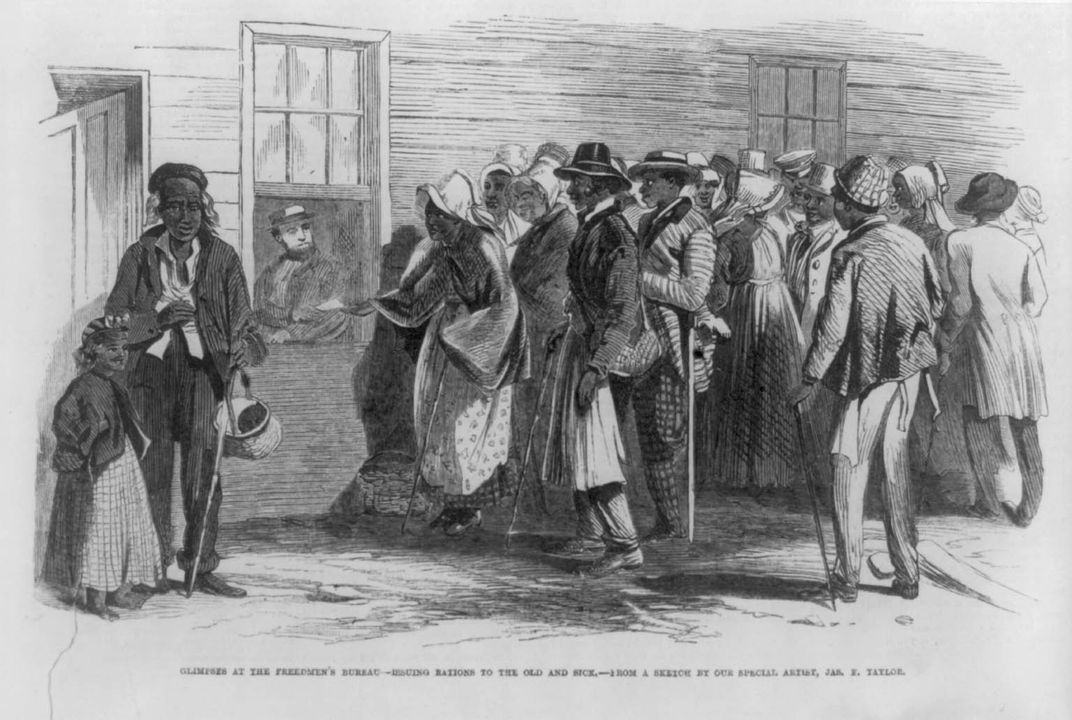

“We have scholars who want chunks of data on smallpox. They want records on labor contracts, and on the rates of labor that they were negotiating for,” Gentry says, adding that some of the labor contracts involve people negotiating for room and board or goods. “Now to the average person they’re looking at something like pots and pans and clothing. But what that does is reveal something about their personal tastes, their socio-economic status. It is one thing to negotiate for a pair of pants. It is another to negotiate for suspenders and a necktie.”

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/12/0f/120fa754-fbd4-4407-8b2c-2c9d20d7e0ce/004567391_00358.jpg)

That gives anthropologists and sociologists the kind of data they can use to analyze what was going on in the communities just before, during and after the Civil War. They can use the information to determine who has power, and who is successfully learning the art of negotiation in a way that helps their families.

“The Freedmen’s Bureau records are the dividing line,” Gentry says. “We get to see people emerge in their own right, doing and saying what they think and believe and some of them are very poignant and some of them are very sad. There are families trying to reunite, and families trying to claim their children.”

The records people are being asked to help transcribe on Douglass Day came from the National Archives. Congress established the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands in 1865. It was tasked to help with the reconstruction of the South, and to help formerly enslaved people transition to freedom. The Freedmen’s Bureau kept handwritten records including everything from labor contracts to letters to lists of food rations issued. It was also meant to protect freedmen and women from assaults by Southern whites.

In 2015, the museum partnered with FamilySearch.org, the non-profit leg of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, to index two million microfilmed Freedmen’s Bureau names. The church purchased copies of the microfilm, and the museum helped the church recruit volunteers to index those names, Gentry says. More than 25,000 people in churches, universities and genealogy societies helped with that effort, which was completed in 2016. Now, the museum is taking the next step.

“What we’re doing is taking that same data and combining that with our transcription projects. One part is just pulling the names off of select images. The other part is transcribing all of the data on all of the images,” Gentry says. “The reason why we’re doing this is to extract more relevant, more in-depth information rather than just simply looking for names.”

That means taking close to two million image files and transcribing word for word all of the other data. There are multiple different sets of records per state, ranging from assistant commissioner’s records to education records and data from field offices. The musuem’s experts started with North Carolina, and about 17 percent of those records have been transcribed. But that is only 6,000 documents so far, out of only one set of records from a single state. And then there’s the question of keeping it all organized enough to be useful.

“We just have an image file with . . . very little information on each page as to where it’s from or what part of the record it comes from,” explains Doug Remley, a museum staffer working on the project. “So what we’ve done is gone through and added . . . subjects—so that hospital records show up under medical records. Court records get 'law' as a subject.”

Instead of forcing people to search for their ancestors page by page in a library, the Smithsonian is in the process of linking all the transcriptions to a central, more easily navigable database. As things get updated in the transcription center, the search application will be updated as well. The whole process means that the museum will have a chance to do further research on objects it already has in its collection as more information turns up in the database. Remley says it also gives people the chance to feel like they are part of building the museum, simply by taking a little time and transcribing a record or two.

But for Kamilah Stinnett, in the museum’s Family Center, the coolest thing about the transcription project is that it allows what she calls “the everyday person” the chance to discover their own history.

“Imagine what it’s like if you’re transcribing stuff from North Carolina and you happened upon your family member, and then have an opportunity to learn about them in a way you haven’t before,” Stinnett says. “And you’re the one that gets to do it! Not a scholar or someone with some fancy degree that you never get a chance to interact with that has no connection to you or your family. You’re the one who can do it. I think that is what is so appealing, and powerful about all of this.”

Douglass Day, and the transcribe-a-thon, will be held on February 14. Register to participate at the Smithsonian Institution Transcription Center. Check out these nationwide Douglass Day events sponsored by the Colored Conventions Project.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/allison.png)