From Virginia to Missouri to the Smithsonian: Jefferson’s Tombstone Has a Long Story

At the institution for a year of repairs, the president’s gravemarker calls the University of Missouri campus home

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/1a/0e/1a0ec614-3df0-437d-9eae-78ccdd6d77a5/jefferson-granite.jpg)

After being sealed with a temporary consolidant, packed and moved with an art shipper, Thomas Jefferson’s tombstone arrived at the Smithsonian Institution for badly needed repairs on Wednesday, February 6. But it didn’t arrive from Jefferson’s famed Monticello estate in Virginia where the third president is buried. Instead, it found its way to the expert hands of senior objects conservator Carol Grissom by way of the University of Missouri’s campus.

The story of how the tombstone got from Virginia to Missouri is a murky one.

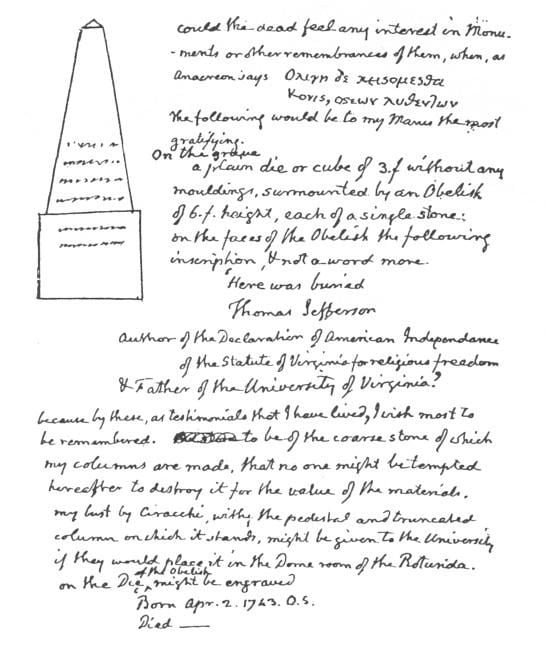

It wasn’t until 1833, seven years after Jefferson’s death, that the monument was erected. Jefferson himself had specified that the tombstone should consist of three parts, a 6-foot-tall granite obelisk atop a granite base, bearing his birth and death dates, and a marble plaque affixed to the obelisk with a special inscription:

Here was buried

Thomas Jefferson

Author of the Declaration of American Independence

of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom

Father of the University of Virginia

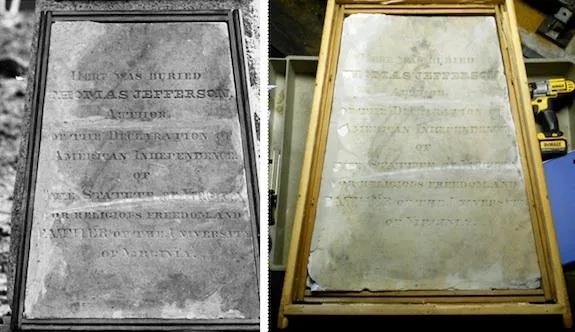

Once the tombstone was erected at Monticello visitors almost immediately began chipping pieces of the obelisk for themselves as souvenirs, slowly destroying the structure. The marble plaque was moved indoors in the mid-1800s. In 1883, both the plaque and the obelisk were granted to the University of Missouri.

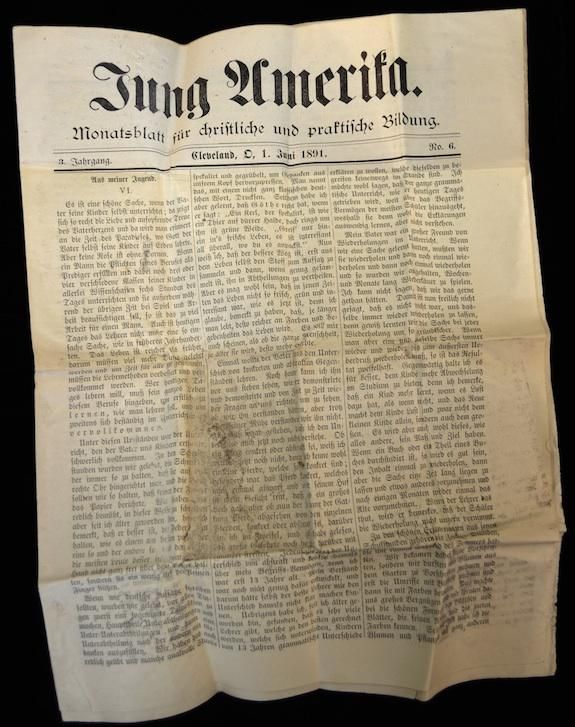

“The evidence is a little skimpy,” says Grissom, adding that there was a professor at the University of Missouri, one A.F. Fleet, who was originally from Virginia. “I think he probably courted one of the descendants and I know that he made arrangements for the shipping.” One of Jefferson’s great granddaughters wrote of the tombstone that family members felt “that in no other state in the union would its poor, battered, weather-worn front have met with such a welcome.”

People also speculate that, like the professor A.F. Fleet, many residents of Columbia, Missouri, originally hailed from Virginia, and that because it was the first school founded within the territory that Jefferson secured with the Louisiana Purchase, the University of Missouri would be a fitting home for the grave marker.

One thing that is clear, Missouri living has been hard on the object.

On a visit to the Columbia, Missouri, campus in September to look the artifact over, Grissom found the marble plaque stored in the corner of an unheated attic. While the granite obelisk still remains on display at the campus, this piece of it had been moved indoors to spare it from damage. Grissom and her team decided to take the project on free of charge. “This just seemed like such a special piece, and the University didn’t have the expertise to do it there, so that’s how it happened that it came here. It’s rather rare now, I would say, that we take anything from the outside.”

Grissom says when the plaque finally arrived, she was excited, but realized she had her work cut out for her.

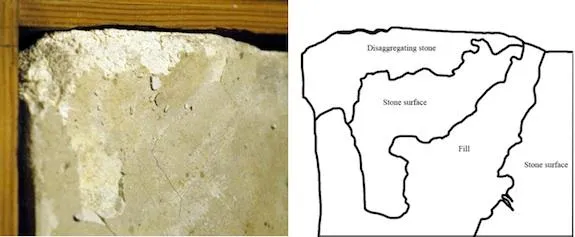

“It’s been broken into five pieces,” she says, “and the top surface is really dirty. It wasn’t put back together terribly well and some of the edges of the stone are very fragile.” Grissom says, “Some of the stone is just sugaring.” Meaning that like sugar, when you touch it, it falls apart. “It is really bad on the corners, in particular,” she says.

In addition, Grissom says, the surface has a lot of irregularities, likely from materials added to the marble over time. “The original part has been stuck down on a new piece of marble and there’s a lot of mortar between those used to attach it. And there’s also a certain amount of fill material on the surface especially at the edges,” she adds. The mortar and fill material likely contain soluble salts that have seeped into the stone and damaged it. Fortunately, Grissom says, much better materials exist now for her to work on repairs and help strengthen the object.

Now in a laboratory in the Smithsonian’s Museum Support Center, Jefferson’s tombstone will stay for about a year while Grissom works to protect it from further damage. She also hopes to do some detective work to find out where the marble came from originally. Her guess now is either Vermont or perhaps the famous marble quarries in Carrara, Italy.

The ultimate plan is to be able to display the object indoors in the first floor lobby of the University’s Jesse Hall, where the plaque may at last be able to take its final rest.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Leah-Binkovitz-240.jpg)