This Game of Monopoly Is Made Entirely of Clay

Kristen Morgin’s playful illusions explore ideas of abandonment and the American dream

Kristen Morgin’s sculptures are astonishing in just how insignificant they at first appear. A viewer might confuse them for a collection of decades-old knickknacks or vinyl records, selected and assembled to evoke a sense of disuse and decay. But a closer look reveals that the aged blocks or figurines or a VHS copy of Grease are not those things at all. They are almost exact copies, but created with unfired clay.

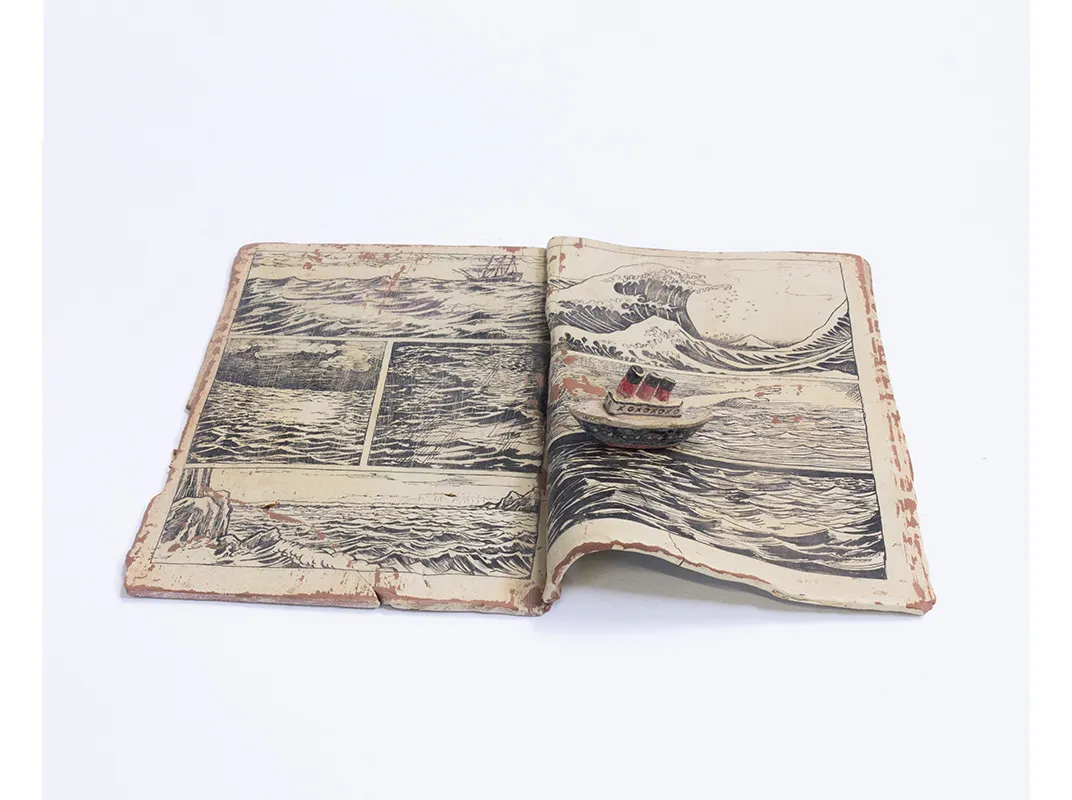

These works, which are on display as part of the exhibition Visions and Revisions: Renwick Invitational 2016, are what Morgin calls, “little monuments to these pieces of ephemera.” They attempt to conceal the clay with which they are made. They look instead like cardboard or plastic or colored paper, creating what Morgin calls “a kind of illusion in the objects.”

The pieces selected for the Invitational cover more than a decade-long span of Morgin’s career, and show that while she has long been attracted to themes of abandonment and Americana, she has explored them at very different scales throughout her career.

Morgin first became interested in the artistic potential of unfired clay while studying for her MFA at the New York College of Ceramics at Alfred University. She started experimenting, creating works that resembled partially exposed objects buried in boxes of dirt. She found inspiration in building ruins near her upstate New York campus and found that to give her sculptures the appearance she wanted, she would need to use an unconventional process.

“Clay changes chemically when you fire it—it turns almost to stone,” says Morgin. “So at the time it really seemed to make sense that I would leave it unfired—it looked dirty. Clay looks great when it looks like itself.”

She continued making objects in this dilapidated and disintegrating style for years before shifting to incorporate different objects and materials. These included wood and wire armatures, or mixing the clay with glue and cement to give it a different color and texture. Her first solo exhibition, held in Cuesta College in San Luis Obispo, California, included nine life-size cellos and trumpets, as well as animals and cups.

She used clay to recreate objects “that I coveted or wanted to learn more about.” For example, creating Piano Forte in 2004, modeled on Beethoven’s piano, led her to not only learn how to build the object itself, but to explore the wider history of the composer and his work.

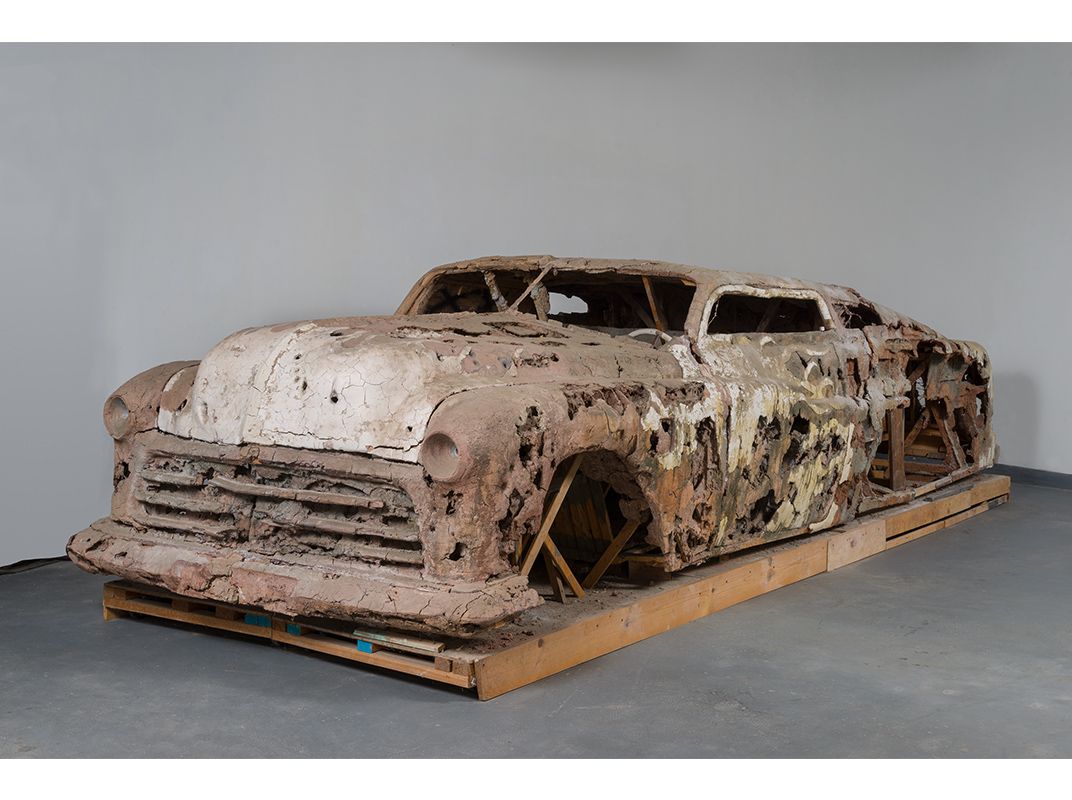

In 2002, she turned to creating full-size unfired-clay cars. She built works such as 2005’s Captain America, included in the Renwick Invitational. Inspired by the 1951 Mercury Lowrider driven by James Dean in the film Rebel Without a Cause, 2005’s Sweet and Low Down (also included in the show) gave Morgin the opportunity not only to create the automobile she “coveted,” but to delve into car culture as well (living in Los Angeles at the time, after growing up in San Jose, the local obsession was a novelty).

The spirit of Los Angeles infuses much of her work from this period, as Morgin explores ideas of the American dream, Hollywood and fantasy versus reality.

“At that point all my work was pretty dirty and old and dilapidated, and I wanted to get away from that,” says Morgin.

Instead of continuing to create ever larger and more extravagant objects, Morgin instead turned inward and smaller, at “things I carried with me from apartment to apartment.”

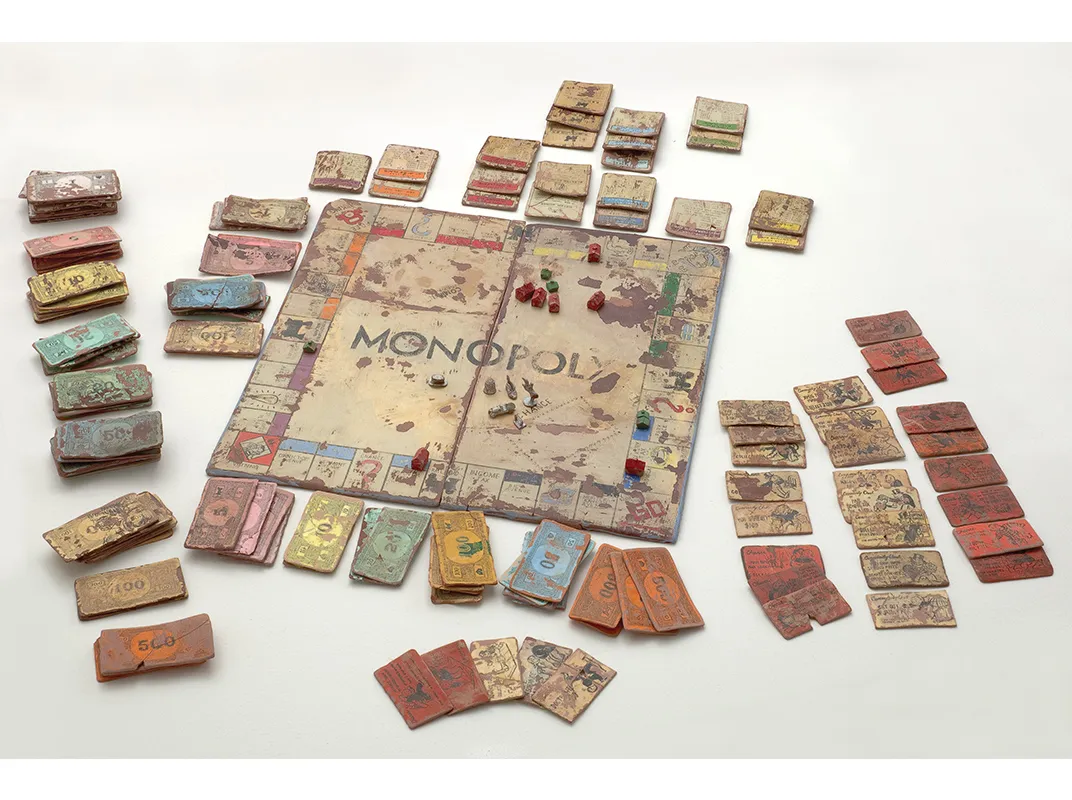

These included picture books, toys, and even the board game Monopoly.

The Monopoly game began whimsically. Morgin says she “was out of ideas of what I wanted to make” and she saw the game in her studio and decided to try and recreate it as faithfully as possible, down to the individual pieces, eventually creating the work on and off for almost a year. As with her earlier sculptures, the process expanded beyond creating the physical object, to Morgin herself working to learn the history of the game, how its creator personally created it in his garage and sold it to friends or gave it as gifts, personally typing out the deeds and play money.

“I thought it was interesting to think about how in a way, since the game was invented, I was the first person to make it by hand,” says Morgin. “I like the idea of making this mass-produced thing by hand. Morgin admits that there is a kind of humor in creating a monument to such mundane objects. She sees her recent work as “a commentary on the value of things: The value of dirt is nothing, but it is also the stuff we walk on and supports us—it’s valueless but also essential.”

At their essence, these sculptures are simply “painted dirt,” but with consideration of the time and effort the artist puts into them, the dirt is elevated and its value increases.

But these monuments were designed to disintegrate, made with the fragile unfired clay, so “a lot of the original objects would have a longer lifespan than the monuments.”

Recently, she’s been making objects like puppets, comic books and records, which Morgin describes as a sort of collage in which she makes all the elements, whether stickers, a torn cover or doodles. For example, Snow White and Woodland Creatures appears to be an assemblage of found objects—scraps from magazines and several playing cards on which an illustration of Disney’s Snow White has been drawn. In fact, Morgin created every detail with painted, unfired clay.

While the Bob’s Big Boy doll, Snow White puppet head and other objects that make up 150 Ways to Play Solitaire carry the appearance of a child’s forgotten toys, this is all an invention by Morgin. Or, as the artist calls it, “an illusion of history about the object.”

"Visions and Revisions: Renwick Invitational 2016" is on view on the first floor of the Smithsonian American Art Museum's Renwick Gallery in Washington, D.C., through January 8, 2017.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/Alex_Palmer_lowres.jpg)