The Descendants of Abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison Donate Family Heirlooms

Objects belonging to the anti-slavery advocate spent a century collecting dust in an attic. Now they’re on their way to the African-American history museum

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/90/a2/90a2f507-ec24-495a-b718-2ccf23e0f16d/2014-02955.jpg)

Growing up, the descendants of abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison knew the attic was off-limits. The Victorian house near Boston had been in their family since the turn of the 20th century, and as family members passed away, heirlooms accumulated on the top floor. When the Garrisons decided to sell the house four years ago, they moved those heirlooms into storage. Last week, the family donated ten of them, including stunning photographs, a watch and Civil War weaponry, to the National Museum of African American History and Culture, set to open in 2016.

Garrison, who was white, helped found the American Anti-Slavery Society, the first abolitionist society to include both blacks and whites. “It’s really the bedrock for where white America begins to demonstrate inequality with African Americans,” says museum curator Nancy Bercaw. In 1831, Garrison founded The Liberator, an anti-slavery publication that Bercaw says likely inspired the Nat Turner slave rebellion.

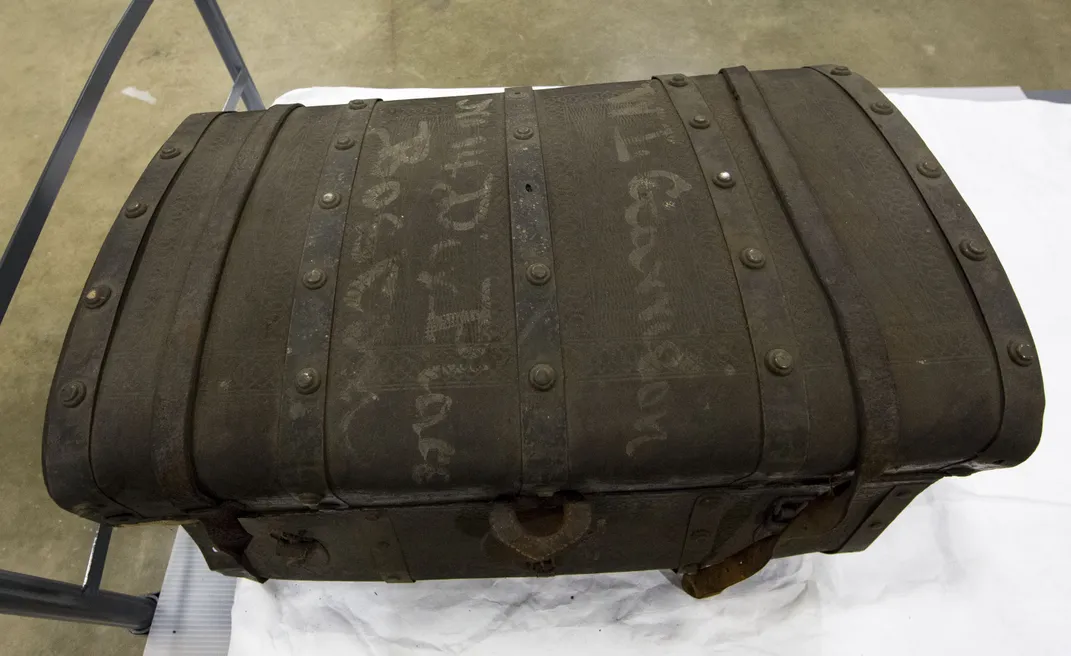

Fritz Garrison, the great-great-grandson of William, first reached out to the museum last November, after learning that the museum had already acquired a Garrison family trunk. In Bercaw's response to Fritz, she wrote, “To date, we could only represent the very full lives of the Garrisons with newspapers and photographs. The possibility of being able to display personal items is thrilling.”

While the Garrison family had previously donated to the Massachusetts Historical Society and the Boston Public Library, Fritz convinced his three siblings and four cousins, all of whom shared ownership of the items, that the new Smithsonian museum deserved the donation. “We wanted to get it into the hands of people who would really show it,” Fritz says. “Millions of people will come through and see these and be affected in some of the same ways that we have been.”

The donation includes a gold pocket watch commemorating the 20th anniversary of The Liberator, given to Garrison by George Thompson, a British abolitionist. The inscription calls Garrison “the intrepid and uncompromising Friend of the Slave.”

Another standout item is a collection of cartes de visite, photographic cards that were designed to be passed between acquaintances. The collection features members of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, one of the first official African-American units during the Civil War, popularized in the 1989 film Glory. “It’s the first time that you see people of color posing the way that they want to pose,” Bercaw says of the 49 photographs. A relative of William Lloyd Garrison served in that regiment.

Fritz and his brother Tim delivered the items to the curators on July 7. Fritz compares the moment of handing them over to “dropping your kid off at preschool on the first day.” “When I packed each item I literally just held it, looked at it, touched it, and really appreciated it,” he says.

Previous Garrison family donations have consisted mostly of documents, and Bercaw says there is something special and relatable about personal objects. “When you take an object that belonged to a specific individual and it’s something very tangible,” she says, “you can actually see that a person just like yourself was capable of doing very great things.”

Editor's Note, July 21, 2014: This article originally stated that Garrison's son served in the 54th Massachusetts Regiment during the Civil War; he actually served in the 55th, another regiment with African-American soldiers and white officers. The article has been amended to correct the error.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/MAx2.jpg)