Global Diplomacy Was in Theodore Roosevelt’s Hands, But His Daughter Stole the Show

Alice Roosevelt’s 1905 journey to Japan, Korea and China is documented in rare photographs held by the Freer and Sackler Galleries

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/17/6a/176a5a4d-c233-43d3-ba36-da308524c61e/arlongworthmanillaweb.jpg)

Alice Roosevelt packed three large trunks, two equally large hat boxes, a steamer trunk, a special box for her sidesaddle and lots more bags and boxes for her grand goodwill cruise to the East Asia in 1905. Among her necessities in those trunks were several bridesmaid outfits she had worn that spring, and petticoats with lace and embroidery ruffles that had their own small trains.

She was, after all, the president’s daughter, which made her a princess in all but title, and she conducted herself accordingly; for all her 21 years she had been the center of attention wherever she appeared. Moreover, the timing of this voyage made certain that amid an 83-member diplomatic delegation including seven senators and 23 congressmen, headed by Secretary of War, future president and chief justice William Howard Taft, Alice would be a brighter star than ever.

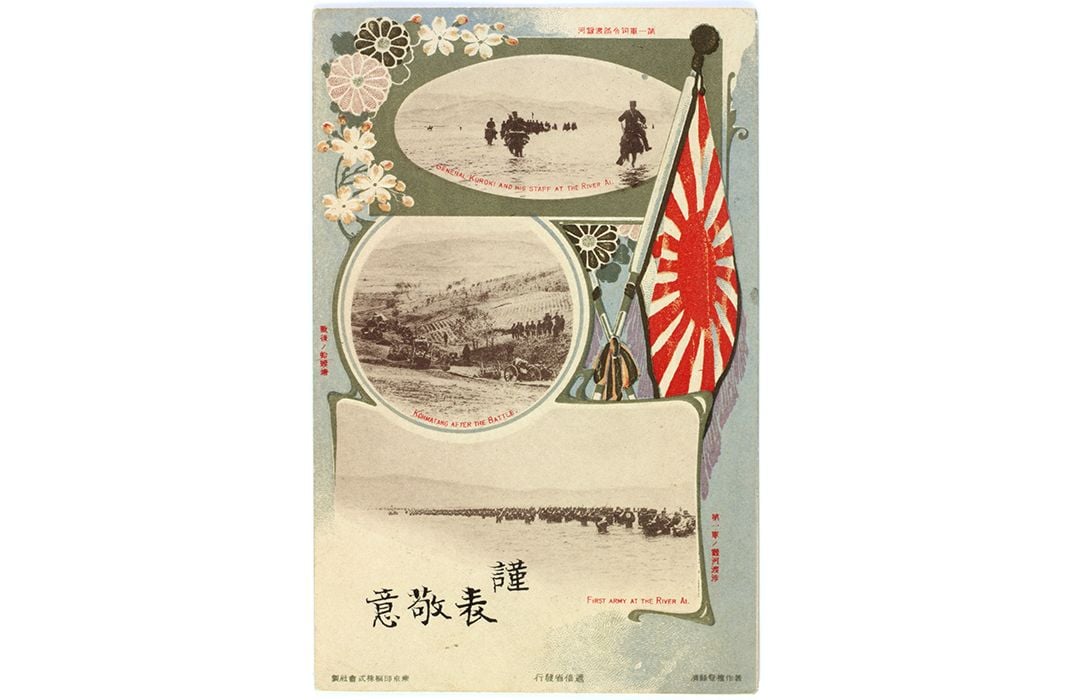

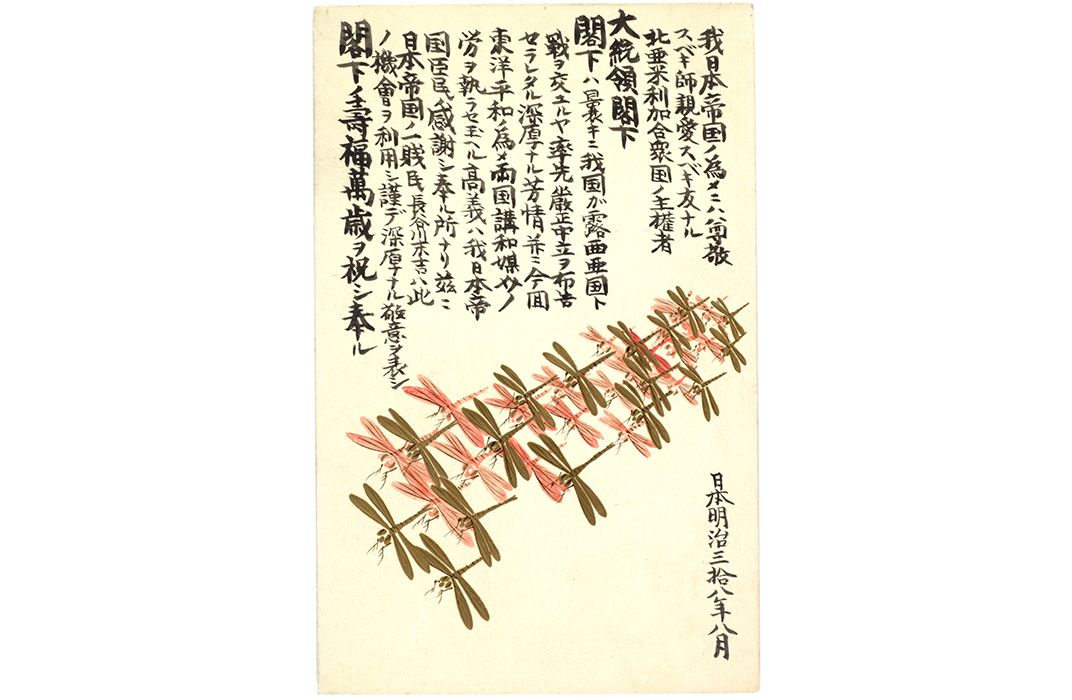

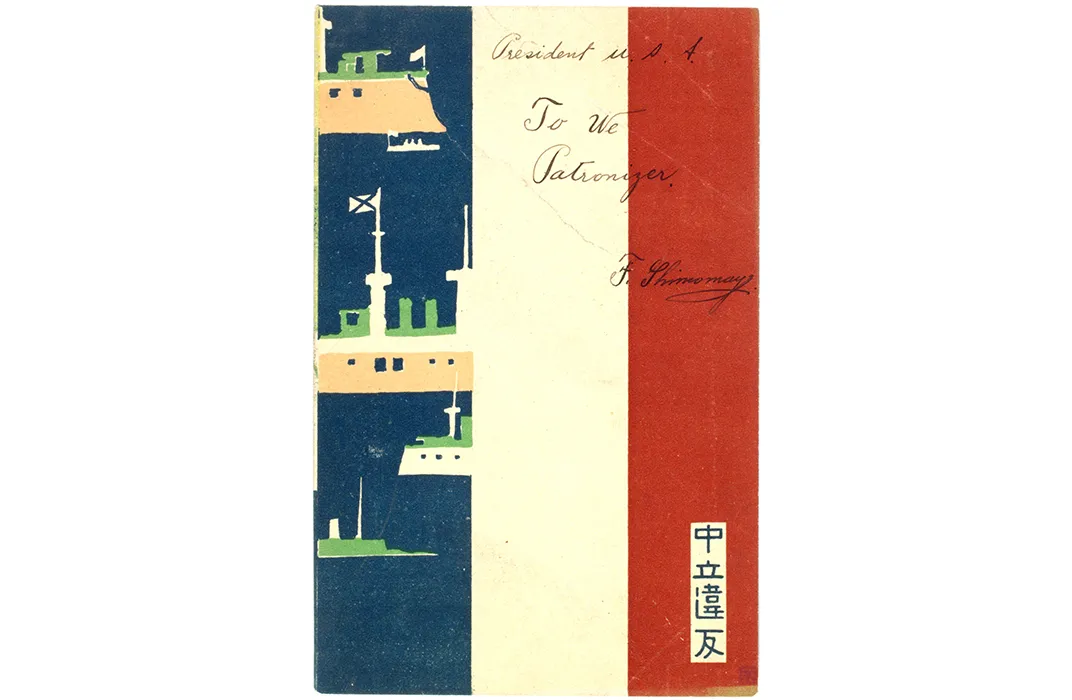

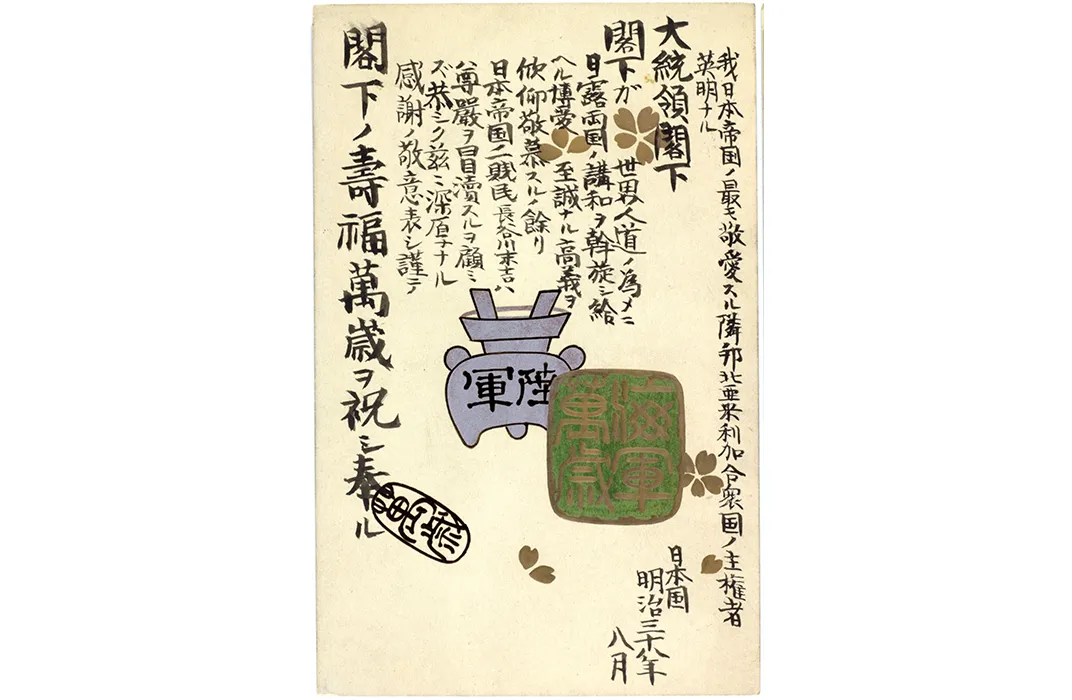

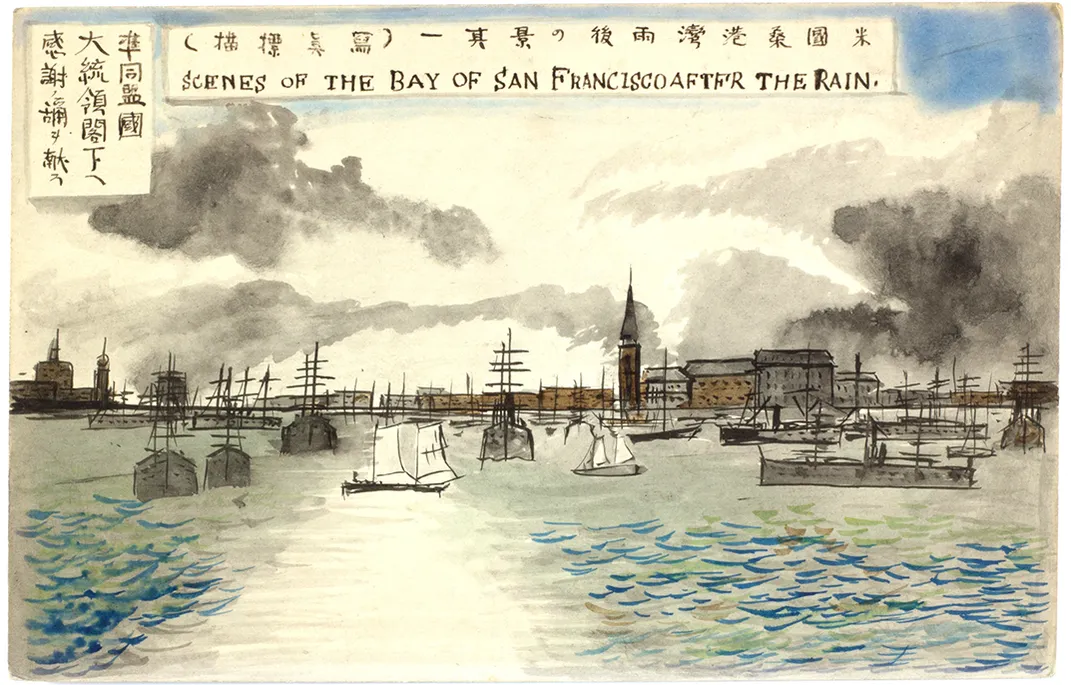

When they sailed from San Francisco aboard the S.S. Manchuria that July 8, her father Theodore was trying to bring Russian and Japanese diplomats together to negotiate an end to a costly war. A few weeks earlier, the Japanese navy had virtually demolished the Russian fleet in the battle of Tsushima. From this position of strength, the Japanese government secretly asked Roosevelt to persuade the Russians to talk peace.

While all this was going on, the irrepressible Alice was lifting the eyebrows of her older shipmates as they crossed the Pacific. She wrote later that she felt it her “pleasurable duty to stir them up from time to time." So she smoked when few ladies did, learned the hula in Hawaii, took a few potshots at passing targets with her pocket revolver and splashed fully clad in an onboard pool.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/12/c4/12c493e2-96f2-4863-8256-474fd5a0d59c/alicerooseveltweb.jpg)

By the time they arrived at Yokohama, the Russians and Japanese had agreed to talk, and anyone named Roosevelt was automatically a popular hero in Japan. The city welcomed them with flags flying and fireworks bursting. On the short trip to Tokyo, crowds at trackside chanted greetings.

For four days in the capital, the Americans were feted more grandly than royalty was usually treated. With countless bows and curtseys, they were presented to the Emperor and his family, and to Alice’s delight, she was loaded with gifts at every turn (“I was a frankly unashamed pig,” she wrote.). But she was not overly impressed by an exhibition of sumo wrestling (“huge, fat,. . .men as big as Secretary Taft himself”).

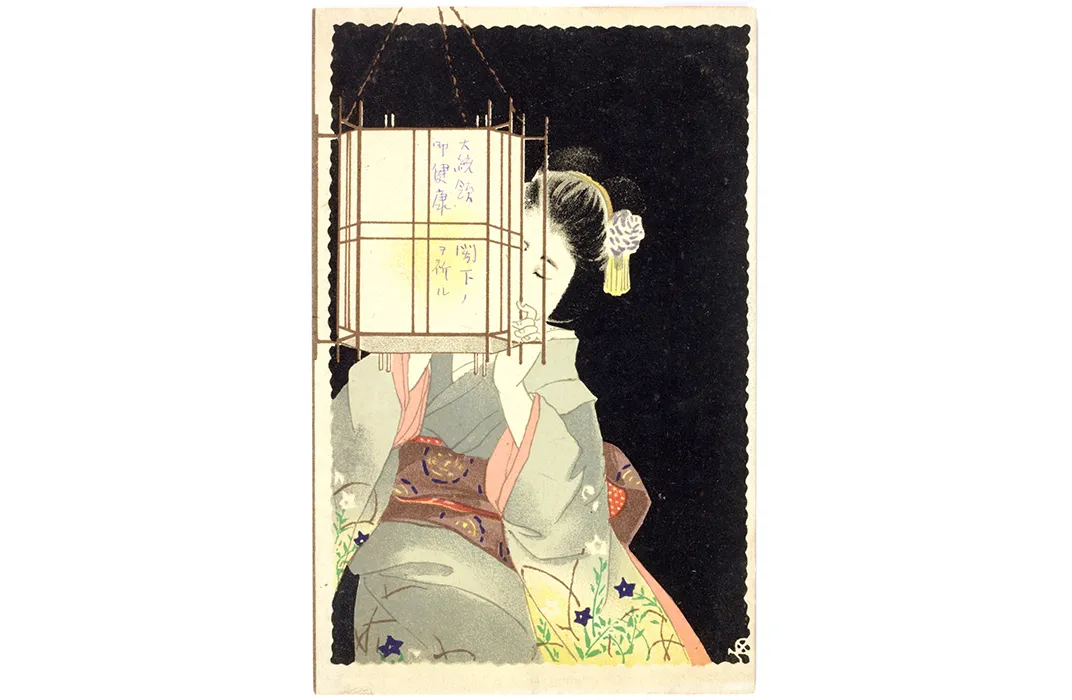

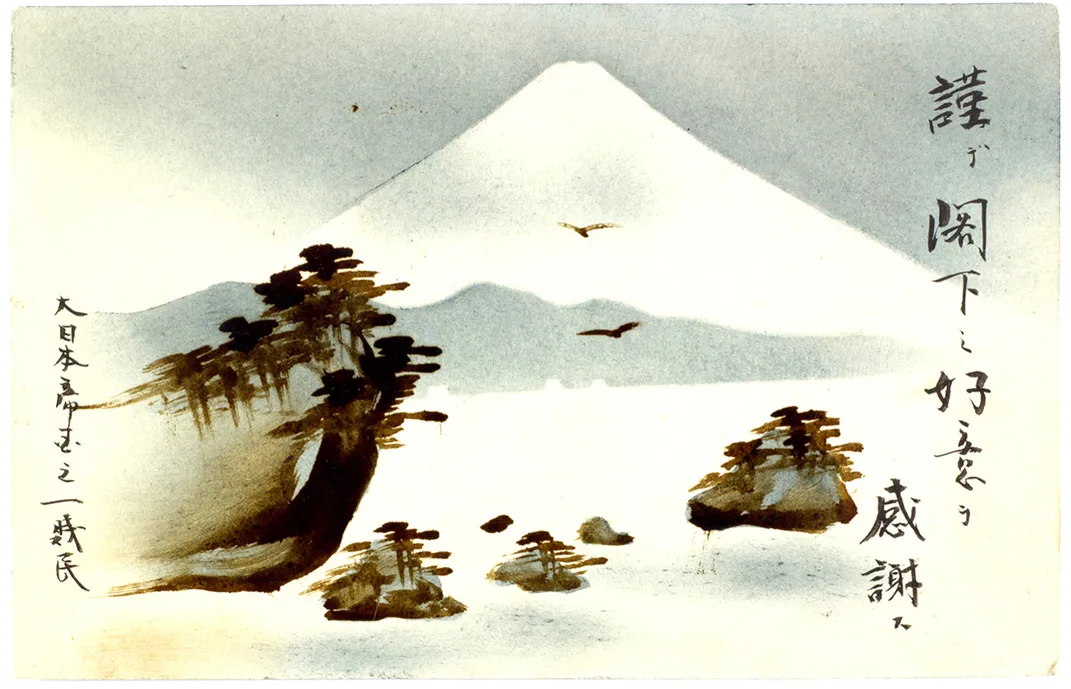

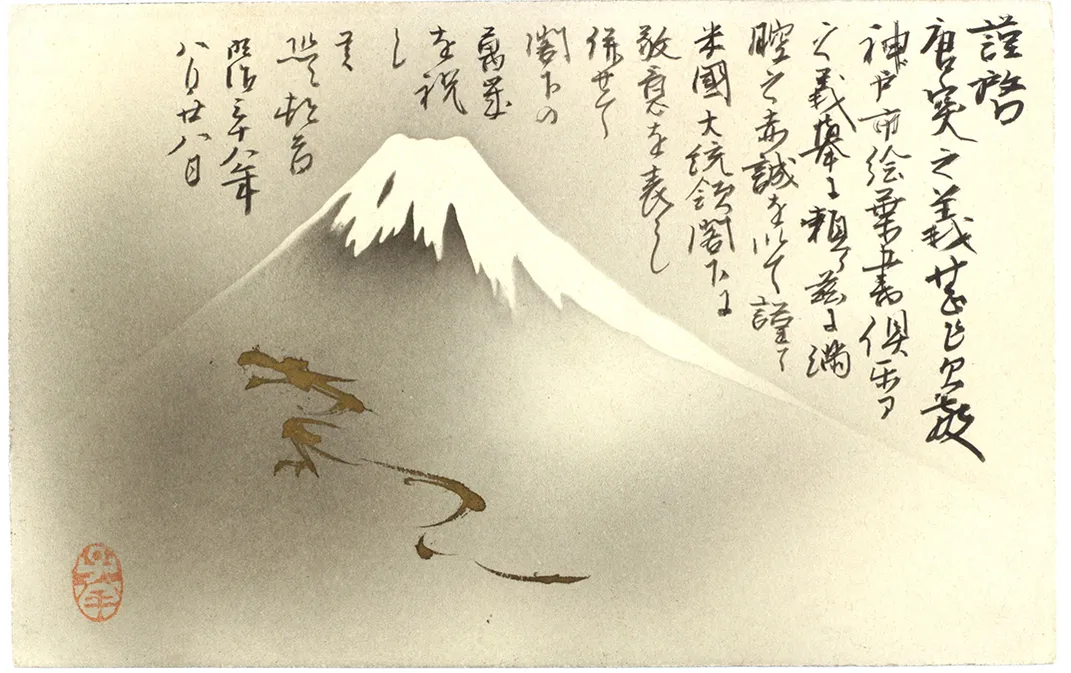

Presumably she did not know that while most of the party was being entertained, Taft himself was having unannounced conversations with Prime Minister Katsura. Those resulted in a memorandum of understanding that would remain secret for 20 years. In it, the two nations would acknowledge each other’s strategic interests in East Asia, with the United States recognizing Japan’s domination of Korea while Japan disavowed any aggressive designs on the newly acquired American sovereignty over the Philippine Islands. Consolidating that Philippine link was the next purpose of the Taft (and Roosevelt) voyage to East Asia. Thousands of paper lanterns lit the station in Tokyo as more shouts of approval sent the delegation off to the ancient Japanese capital of Kyoto, which staged a Cherry Blossom Festival for them although the blossoms of spring were long gone. Then, sailing from Kobe amid more fireworks, they bade Japan temporary goodbye after a brief stop at Nagasaki, a city that would figure in world headlines 40 Augusts later.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/81/bb/81bbc450-fb2b-4712-a04b-ddac44c0102c/tokyosumoweb.jpg)

Although Taft would become President and later Chief Justice of the United States, his earlier service as governor general of the Philippines may have been the most important work of his whole career. After U.S. seizure of the islands in the Spanish-American War, native Filipino forces continued to fight for independence until they were bloodily repressed by American troops. Taft headed the commission that set up a semi-independent government and had earned a benevolent image by the time he departed in 1904.

Now, returning to Manila a year later, he was greeted with what Alice called “extraordinary enthusiasm and affection.” And so, of course, was she.

American flags, soldiers, sailors and marching bands seemed everywhere, and despite beastly hot weather, welcomes and celebrations went on day and night. Alice thought Taft was charmingly light-footed in a traditional dance called the rigadon. (She called it “a sort of lancers or quadrille,” but as performed on Filipino Independence Day 2008 by members of the Filipino-American Association of Greater Birmingham, it looks more like an old-fashioned Virginia reel.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/f1/d9/f1d9130a-ffe8-4723-9588-5acefb2d3c33/arwivesweb.jpg)

From Manila they sailed from island to island, and at every opportunity Alice dawdled with Nicholas Longworth III, the dashing, mustachioed congressman from Ohio who would soon become her husband. Nick had eager competition along the way—on the island of Jolo, during entertainments that Alice said were like “comic opera,” the Sultan of Sulu presented her with a magnificent pearl ring, and the papers back home said he had proposed marriage.

But she managed to remain single as they made their way back to Manila and sailed to their next stop in Hong Kong, en route to Peking (now Beijing). The peak of her visit to the Chinese capital was reception by the Empress Cixi, “one of the great women rulers in history,” who looked down from a throne three steps above the rest of humankind.

On to Korea, by battleship and train to Seoul, which to Alice was a sad sight. She felt immediately that “Korea, reluctant and helpless, was sliding into the grasp of Japan.” By then, she was becoming weary of all the grandeur: after the Emperor received them in “unnoteworthy, smallish” surroundings, she sought distraction by riding into the hills, where she discovered that Korean horses tended to bite foreigners. One, she recalled “seemed to have a particular aversion to me,” so she stood back and made a face at it, and it laid back its ears and bared its yellow teeth, “struggling to shake off the groom in its effort to get at me.”

In early October, she was eager to return to Japan on her way home, but when they arrived there, she was surprised at what she found.

In their absence, Japan and Russia had formalized peace terms by signing the Treaty of Portsmouth. For overseeing it, Theodore Roosevelt would receive the first Nobel Peace Prize ever awarded to an American.

But because of it, Alice wrote, “Americans were about as unpopular as they had been popular before. I have never seen a more complete change.” As victors in the war, the Japanese felt they had been shortchanged by the treaty. Although officials still were typically courteous, public anti-American demonstrations broke out, some so violent that U.S. citizens were advised to identify themselves as English. The last ceremonies sending the American delegation back across the Pacific were nothing like what had greeted them a couple of months earlier.

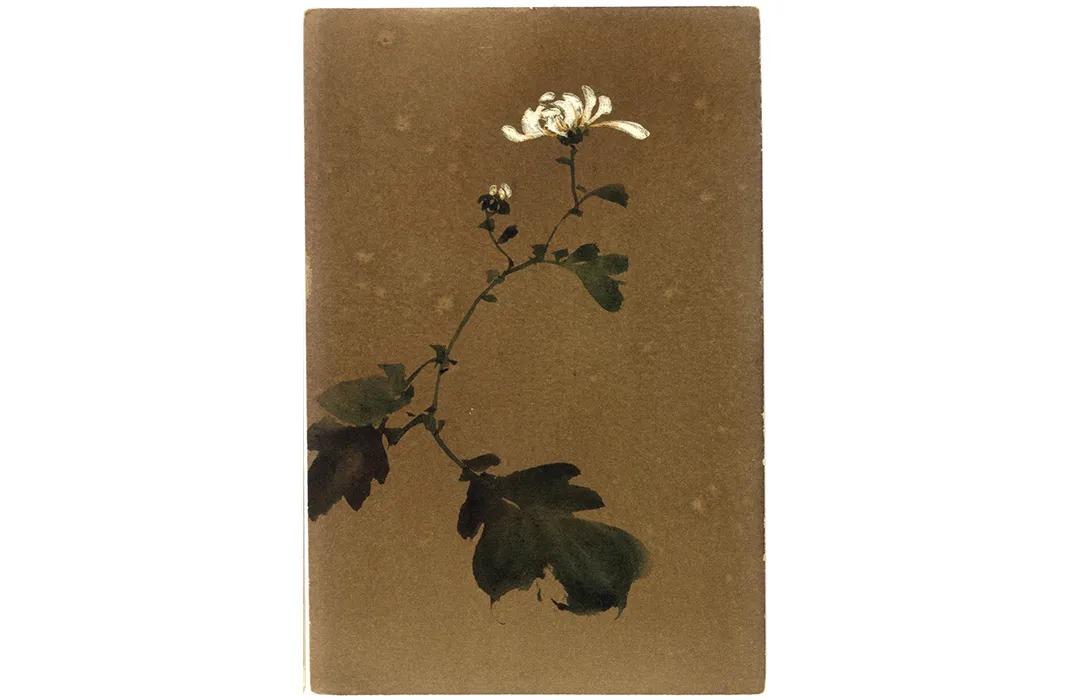

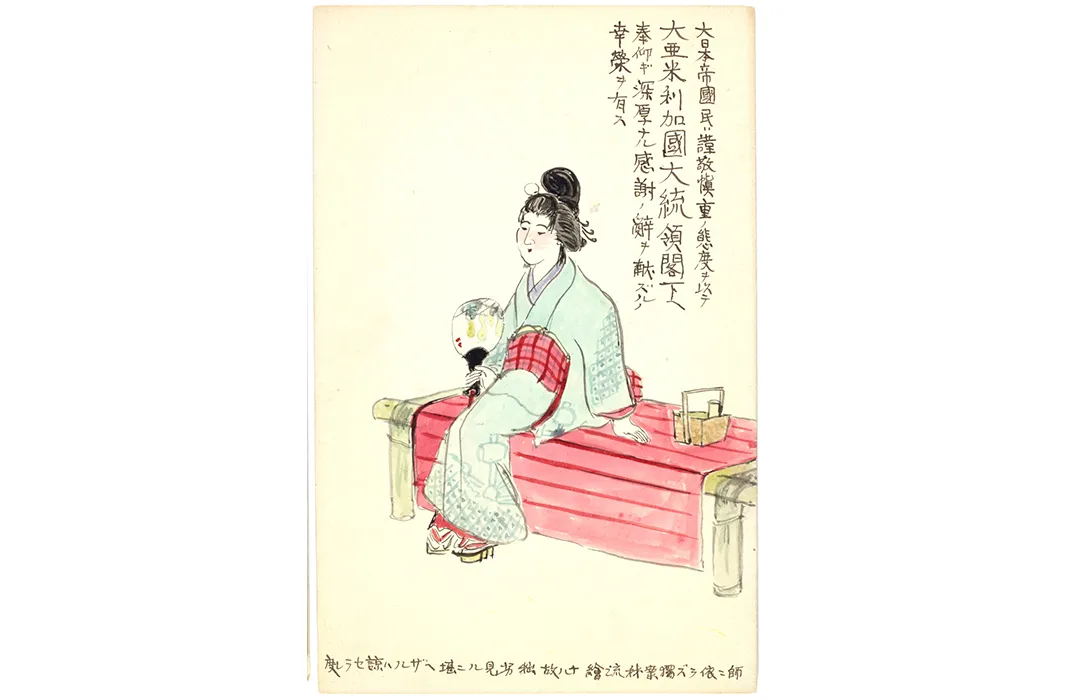

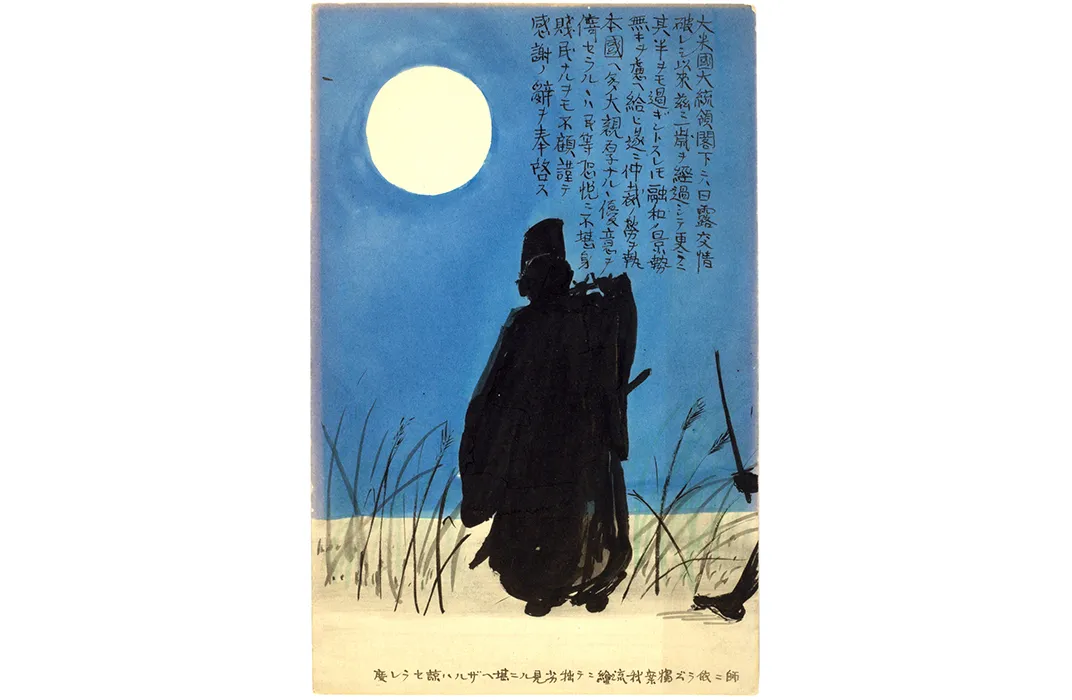

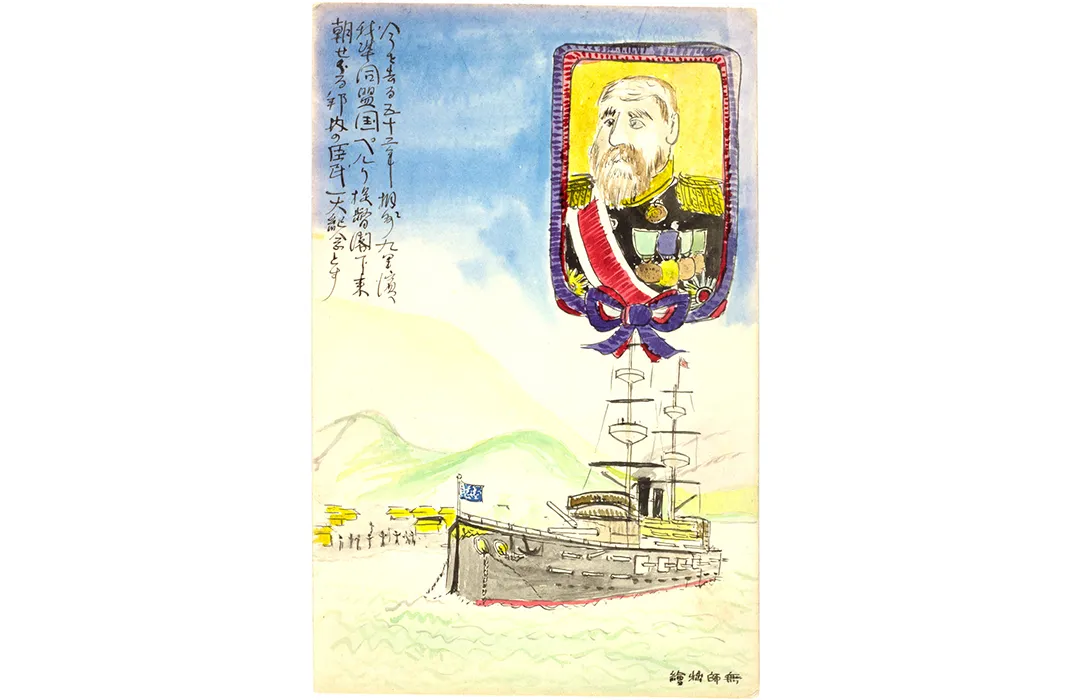

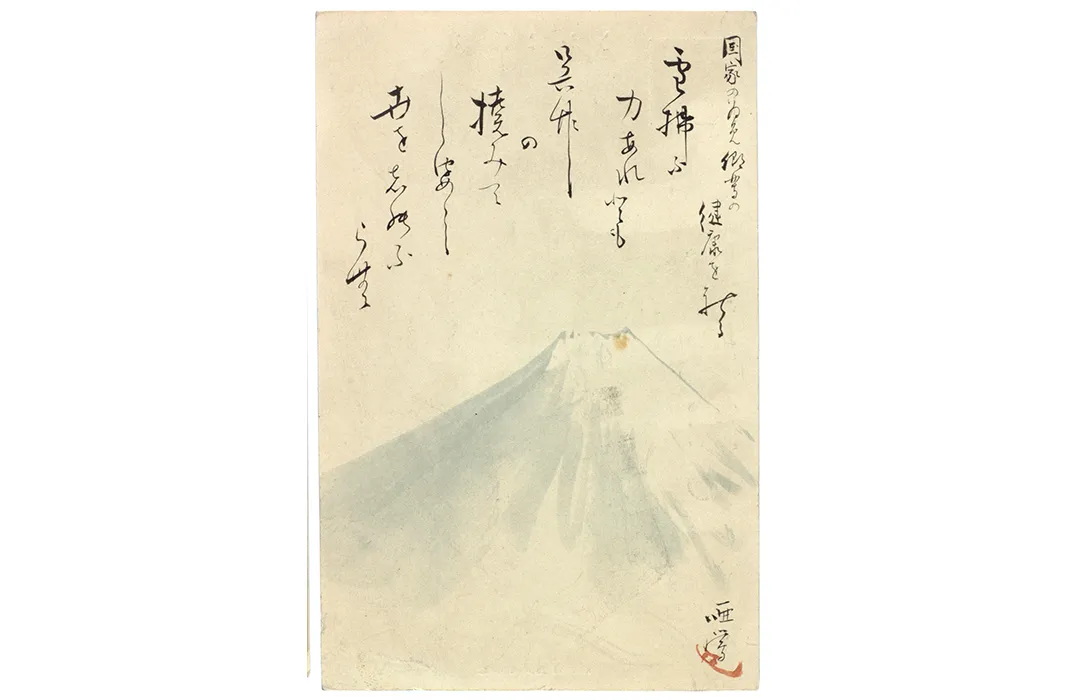

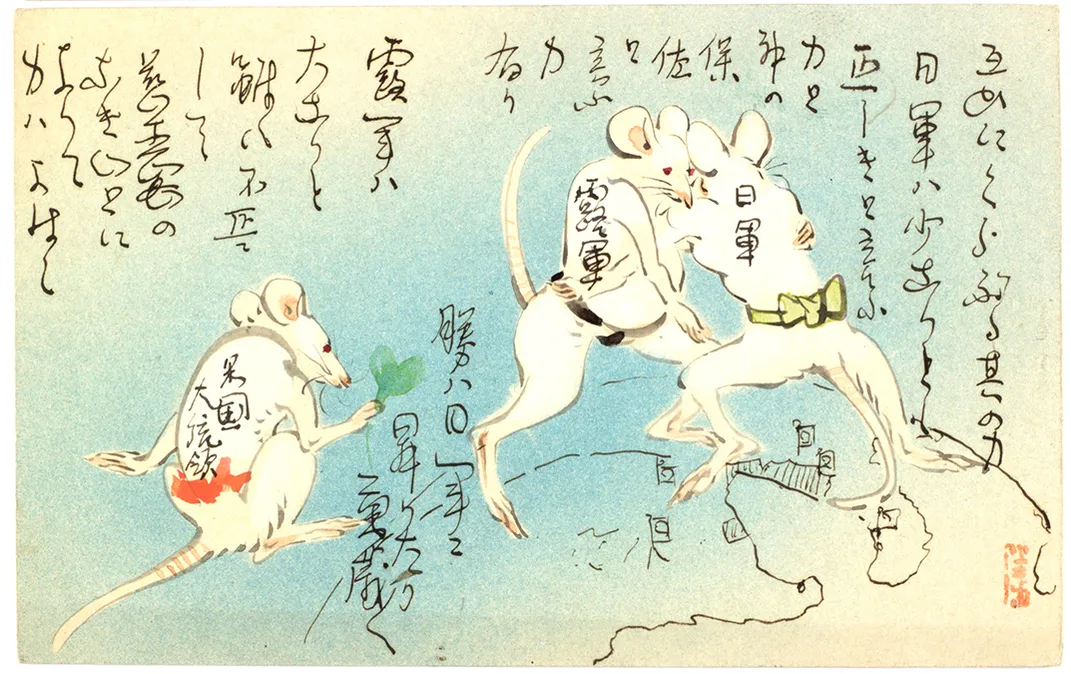

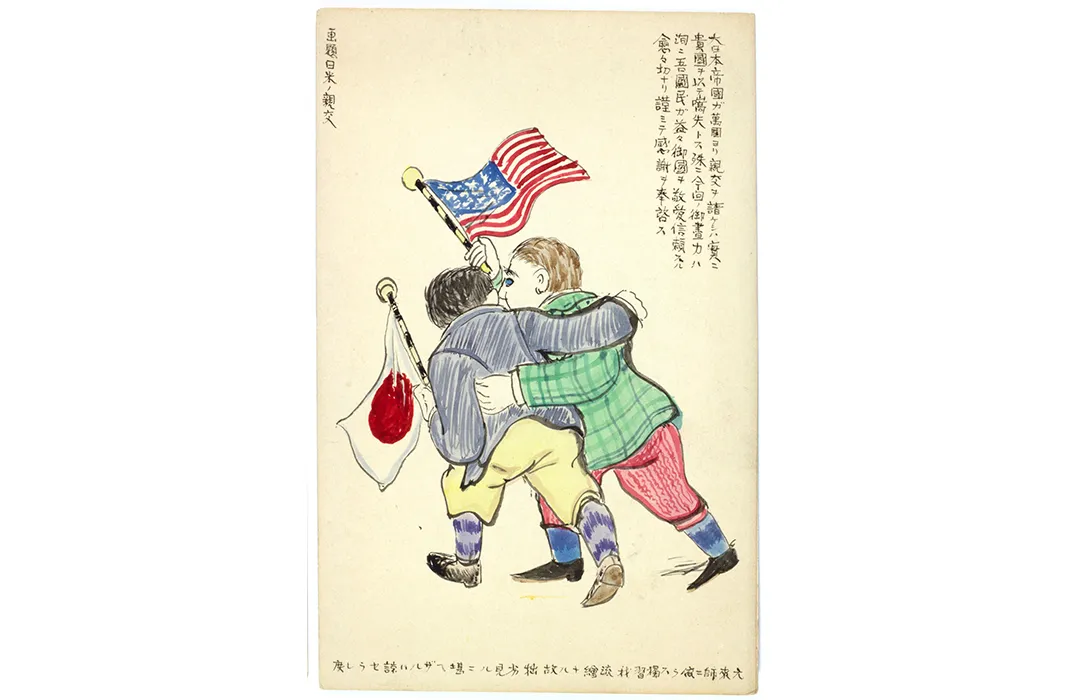

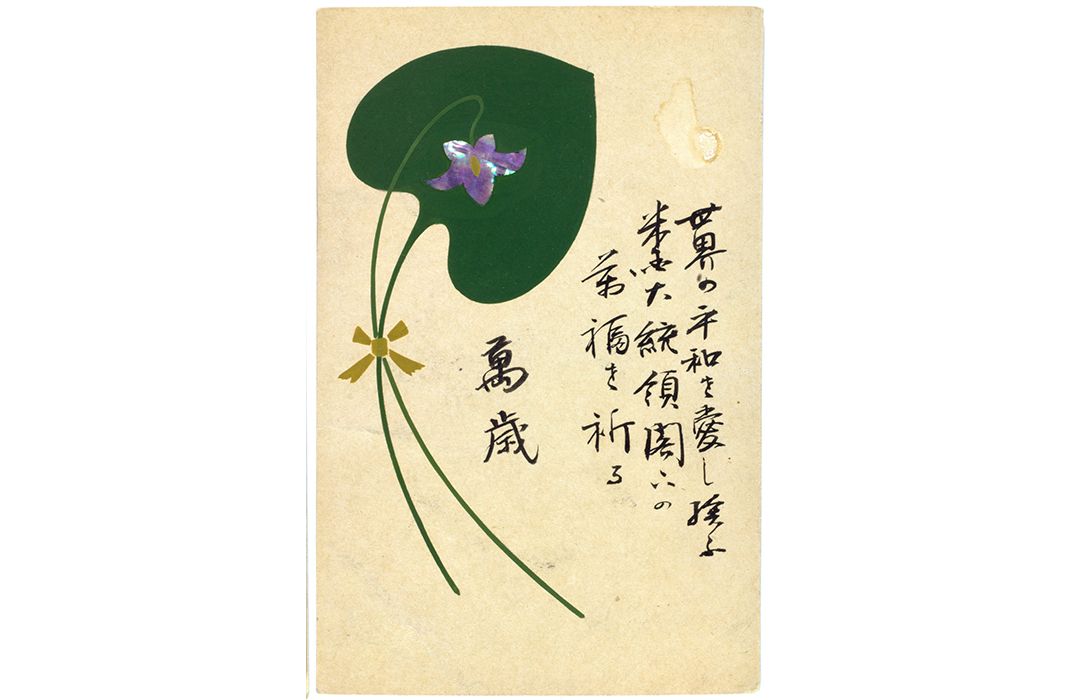

Yet there was one final happy note: Alice was surprised again to receive dozens of beautifully hand-drawn postcards, addressed to her father and celebrating Japanese-American friendship. Many were obviously created before the treaty was completed, in the weeks while Taft, Roosevelt and company toured the Orient. Today those cards, along with imperial portraits and some of the other lavish gifts that Alice brought home, plus hundreds of photographs of the voyage, are a bright feature of the Alice Roosevelt archive in the Smithsonian Institution’s Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C.

"Alice in Asia: The 1905 Taft Mission to Asia" is a new online exhibition highlighting much of the Roosevelt materials and created by archivist David Hogge.

Crowded Hours

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/13/d4/13d42e75-a1cd-4edc-9d1e-410d10feb3b5/fsaa200902pc62web.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/DSCN0003-001.JPG)