Grammy Nod to Folkways’ Pete Seeger Collection Is a Fitting Tribute

The producers aim to inspire future generations to carry on the singer’s legacy

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/15/73/15739708-86c5-43bc-8d4b-447325b5bc12/fp-davi-bwne-0614-07.jpg)

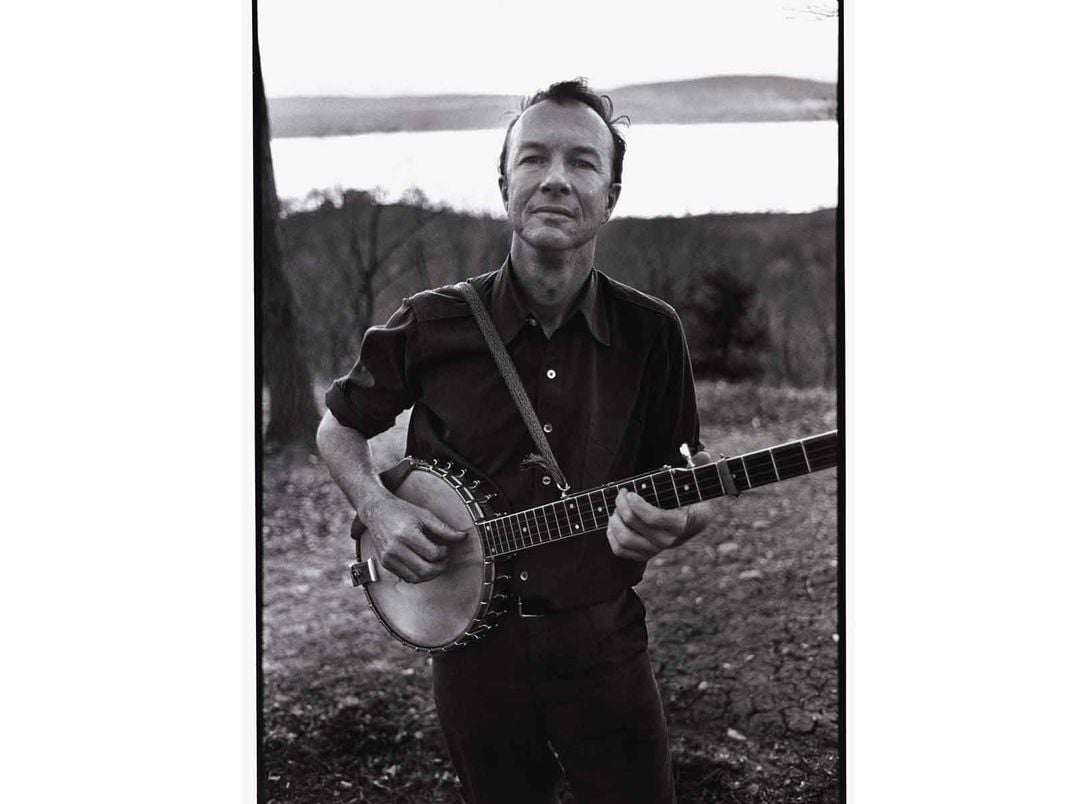

From the late 1930s until his death in 2014, Pete Seeger’s songs calling for fair wages, social justice, a clean environment and world peace have remained relevant. And it is perhaps a fitting tribute that Seeger, a man for all ages, is the subject of a Smithsonian Folkways box set of music and history that last week took home a coveted Grammy award. Although times have changed and “protest” music is focused more on inward struggles, the producers aim to inspire future generations to carry on the Seeger legacy.

“Pete was the living embodiment for how music can act as an agent for social, political and cultural change in this country and beyond,” says Robert Santelli, an author and founding executive director at the Grammy Museum. “When you look at the issues, the challenges that we as a nation are faced with—whether it’s climate change or immigration problems or problems with race—Pete addressed all of those things his entire life, through music.”

“We need to memorialize, preserve, celebrate and then make available to hopefully the next generation of young people all of the musical inspiration that is packed into this box set,” he says.

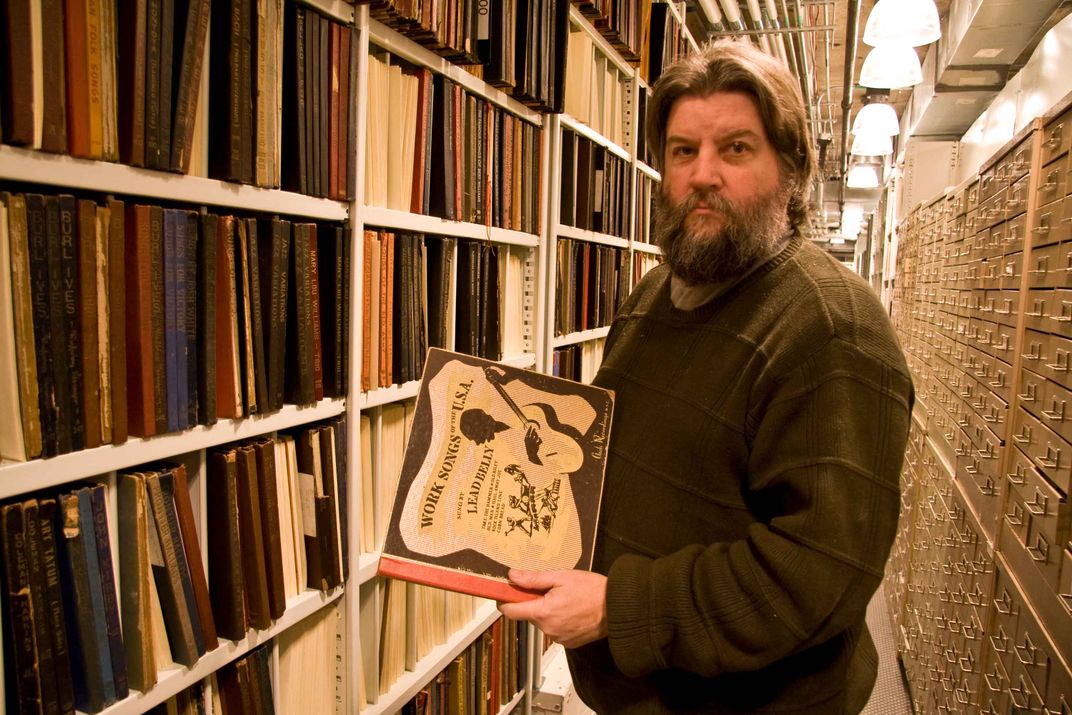

Pete Seeger: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection won in the category for Best Historical Album. The set includes six CDs of some well-known, not-so-well-known, and previously unreleased recordings spanning Seeger’s career, along with informative and thoughtful essays from producers Santelli and Jeff Place, who is the curator and senior archivist at the Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. It is Place’s third Grammy.

Pete Seeger: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection

Pete Seeger: The Smithsonian Folkways Collection is a career-spanning anthology of one of America's most quintessential, celebrated, and influential musicians. Featuring classic recordings, 20 previously unreleased tracks, historic live performances, and special collaborations, this set encompasses over 60 years of Pete's Folkways catalog, released on the occasion of his 100th birthday. Six CDs and a 200-page extensively annotated and illustrated book.

A CD box set still has a place in an era of streaming music—especially at Folkways, says Place. “We’re a museum and we tell stories,” he says. The songs in the set are presented with context—narratives, photos, sheet music, ads for gigs, notes and letters from Seeger. “A song on an iPhone without any kind of information about what the history of this is about, to me, is missing the point,” says Place, adding that the Folkways box sets are like miniature museum exhibits.

Both Place and Santelli knew Seeger and his family, and that familiarity is reflected in the selection of the music and the personal stories included in the liner notes. Place started at the Smithsonian’s Folkways label about the same time that Seeger and his wife Toshi transferred his masters from the original New York-based Folkways label to the institution in the late 1980s. “They put their faith in us and let us keep going with it,” he says.

Place was charged with digitizing the music, papers, album covers and mementos that Seeger gave to Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. Over the years, others sent Seeger-related materials his way giving Place an opportunity to make constant mental notes about what might go into the ultimate collection.

Place and Santelli were instrumental in the creation of a group of box sets devoted to the Holy Trinity of American folk music: Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly and Seeger. The Seeger collection capped off the two previous sets which were released in 2012 and 2015.

Guthrie was a mentor and friend to Seeger and Seeger loved performing Guthrie’s music, including “This Land is Your Land.”

“That song is very much affiliated with Pete,” says Santelli. Seeger and Bruce Springsteen played the popular anthem together in 2009 at President Barack Obama’s inauguration. Springsteen, who released his devotional album We Shall Overcome: The Seeger Sessions in 2006, is one of many musicians directly inspired by Seeger. Janis Ian, Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Tom Paxton, John Mellencamp, Jackson Brown and Tom Morello are among the others, says Santelli.

Seeger was a tireless performer, who was energized by the crowd singing along, which he considered evidence of his ideas taking root. Many of Seeger’s recordings were his versions of folk standards, union songs, spirituals and discoveries from all over the world—usually on banjo, but sometimes on guitar. He saw folk music as a process. “I think one of the more authentic things I do is continually changing things,” Seeger said, adding that change is “much more in the folk tradition of America.”

Place likens Seeger to Johnny Appleseed, spreading seeds of wisdom through his music. “Pete Seeger spent his life single-mindedly fighting for social justice and humankind,” he writes in the liner notes. “For him, the seeds he left behind were ideas and songs.”

The collection includes many live cuts that capture Seeger’s storytelling and infectious enthusiasm. Some of the songs have been immortalized through music class or camp sing-alongs: “House of the Rising Sun;” “Shenandoah;” “Midnight Special;” “Battle of New Orleans;” and “Kumbaya,” for instance. Many listeners will recognize “Wimoweh.” Originally recorded by South African Zulu artist Solomon Linda in 1939, Seeger discovered it, changed it slightly, and had a hit with his band The Weavers in 1957. He made sure royalties got to the Linda family, but the song went viral, and became a hit for dozens of artists over the ensuing decades. Disney used a version that it called “The Lion Sleeps Tonight” in its 1994 film The Lion King, which finally triggered a copyright suit from the Lindas. Disney ultimately settled.

Seeger also shone as a songwriter. He tweaked a Biblical verse to create “Turn, Turn, Turn,” which became a huge hit for The Byrds in 1965. “If I Had A Hammer,” composed with collaborator Lee Hays in 1949, was a massive hit for Peter, Paul and Mary in 1962. The group also had a hit with Seeger’s anti-war song “Where Have All the Flowers Gone,” as did The Kingston Trio, and the song has been recorded all over the world. Seeger wrote “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” in 1967 after seeing a photo of troops in the Mekong Delta during the Vietnam War. The song did not mention Vietnam, but CBS tried to prevent television performance on the "Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour" later that year. Seeger ignored them and played it anyway; the censors cut out the last verse, because they said it seemed to reference President Lyndon B. Johnson.

The 1960s represented a comeback for Seeger, after years of blacklisting by television and by various venues that viewed him as a Communist sympathizer. Seeger had always been left-leaning, outspoken in his support of workers, labor unions and equality. The Joseph McCarthy-led House Un-American Activities Committee indicted Seeger for contempt of Congress in 1958 after he had refused to testify in 1955, citing his First Amendment right to free speech. He was tried and convicted in 1961, but he won on appeal in 1962.

In the early 1960s, Seeger taught civil disobedience and progressive thought at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee. During that time, a colleague brought him a spiritual she’d collected from South Carolina, “I’ll Overcome.” Seeger tweaked it, and “We Shall Overcome” became a civil rights anthem.

Seeger wrote songs and participated in the environmental movement in the 1970s and 1980s and continued to play music and march for various causes throughout his life—even joining the Occupy Wall Street march in 2011, when he was in his 90s.

His music is perennially contemporary, says Place, citing, for instance, the previously unreleased “The Ballad of Dr. Dearjohn,” a Canadian folk song that was modified by two Canadian writers in the 1950s to comment on the nation’s struggle to institute universal health care. The song extols the new national plan: “It’s government sponsored and they pay the bill when you or your wife or your children get ill. It lessens the worry when sickness is near—and there’s something left over for skittles and beer!” But the physician, Dr. Dearjohn retorts, “It’s socialist, communist, and also it’s red!”

When Place heard it, he thought, “this is timely, it should go on this set.”

Santelli believes that Seeger would be diving into today’s battles if he were still alive. “With the threat of climate change being so dramatic and so close, Pete would be on the front lines rallying kids,” he says. “There is no Pete Seeger today, unfortunately, but we have Pete Seeger’s music, and we have his writings as a source of inspiration to move us forward,” says Santelli.

In 2002, Seeger summed up his beliefs, which many would welcome in today’s fraught times.

“Our government must represent us—we, the people. Not just big oil and other special interests. It must recognize that the United States, as the most powerful nation on Earth, has inherited a moral obligation to the people of the world. We must lead by example. We must assume that our vision of egalitarian democracy and civil society applies to people of all nations, colors and faiths, and not just to certain segments of the population within our national boundaries. We need to practice what we preach.”

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/AliciaAult_1.png)