Katsushika Hokusai was in his 70s by the time he created his best-known image, the majestic The Great Wave off Kanagawa. Often known simply as The Great Wave, the popular print not only embodied Japanese art, but influenced a generation of artists in Europe, from Van Gogh to Monet.

Yet it was one of an estimated 30,000 images from Hokusai, who was so frenzied an artist that at one point he signed his work “Gakyō Rōji,” which translates to “the old man mad about painting.” That’s the title, too, of a new exhibition now on view at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art.

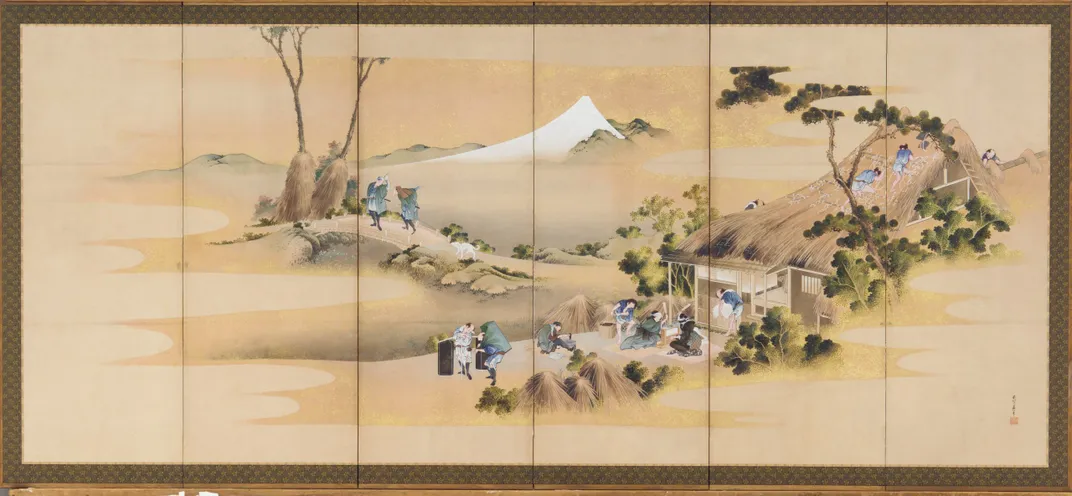

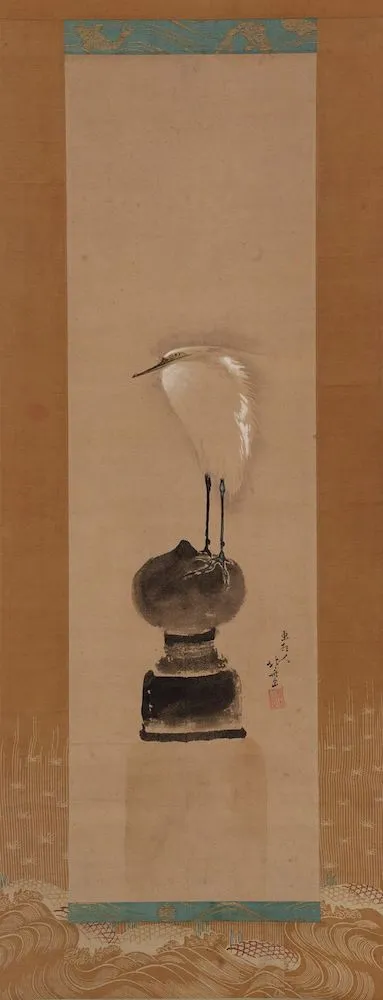

“Hokusai: Mad About Painting” brings forth from the museum’s storage vaults 120 works of art, from six-panel folding screens to rare preparatory drawings for woodblock prints. Because of their sensitivity to light, none have been on view since a hugely popular Hokusai exhibition that took place in 2006; and some so rarely seen, they were not even included in that show.

Hokusai's Brush: Paintings, Drawings, and Sketches by Katsushika Hokusai in the Smithsonian Freer Gallery of Art

Hokusai's Brush, from Smithsonian Books, is a companion to the Freer Gallery of Art's exhibition that celebrates the artist's fruitful career. The Freer, home to the world's largest collection of paintings by Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai, has put on view for the first time in a decade his incredible and rarely seen sketches, drawings, and paintings. Together with essays that explore his life and career, Hokusai's Brush offers an in-depth breakdown of each painting, providing amazing commentary that highlight Hokusai's mastery and detail.

Further, because of advances in technology, some of the works are newly attributed to the influential artist, says Frank Feltens, the museum’s assistant curator of Japanese art. That includes a striking pair of dragons whose images are blown up on the walls of the hallways between the galleries, to an iconic painting of a boy playing a flute in the shadow of Mount Fuji.

The “wave” of the artist’s work at the Freer, in fact, represents the “largest collection of Hokusai paintings in the world,” says Massumeh Farhad, the Freer’s interim deputy director for collections and research.

The new show, which runs deep into next year, will mark both the 260th anniversary of Hokusai’s birth next year, and the centennial this year of the death of the museum’s founder Charles Lang Freer—the Detroit industrialist, who after amassing a collection of Asian and American art, donated it all to the United States in 1906 to create the nation’s first art museum.

“To think that Mr. Freer collected all of these more than a century ago,” says Shinsuke J. Sugiyama, the Japanese Ambassador to the United States. “All these years later, I’m amazed at his foresight and his desire to understand a part of the world that was so different from his and his deep appreciation of art that was non-Western.”

Since then, Hokusai, and in particular his Great Wave, crashed over the world, becoming one of the most recognized images in the art world. The famous work can be found on an interior page of the Japanese passport with others from the artist's Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji. It inspired Debussy and, the ambassador noted, “online, you can buy Great Wave dog bowls, Great Wave socks, or Great Wave stamps and hoodies.”

And yet, reproduced in the thousands when Great Wave was released in the early 1830s, the woodblock image is one that isn’t in the museum’s collection.

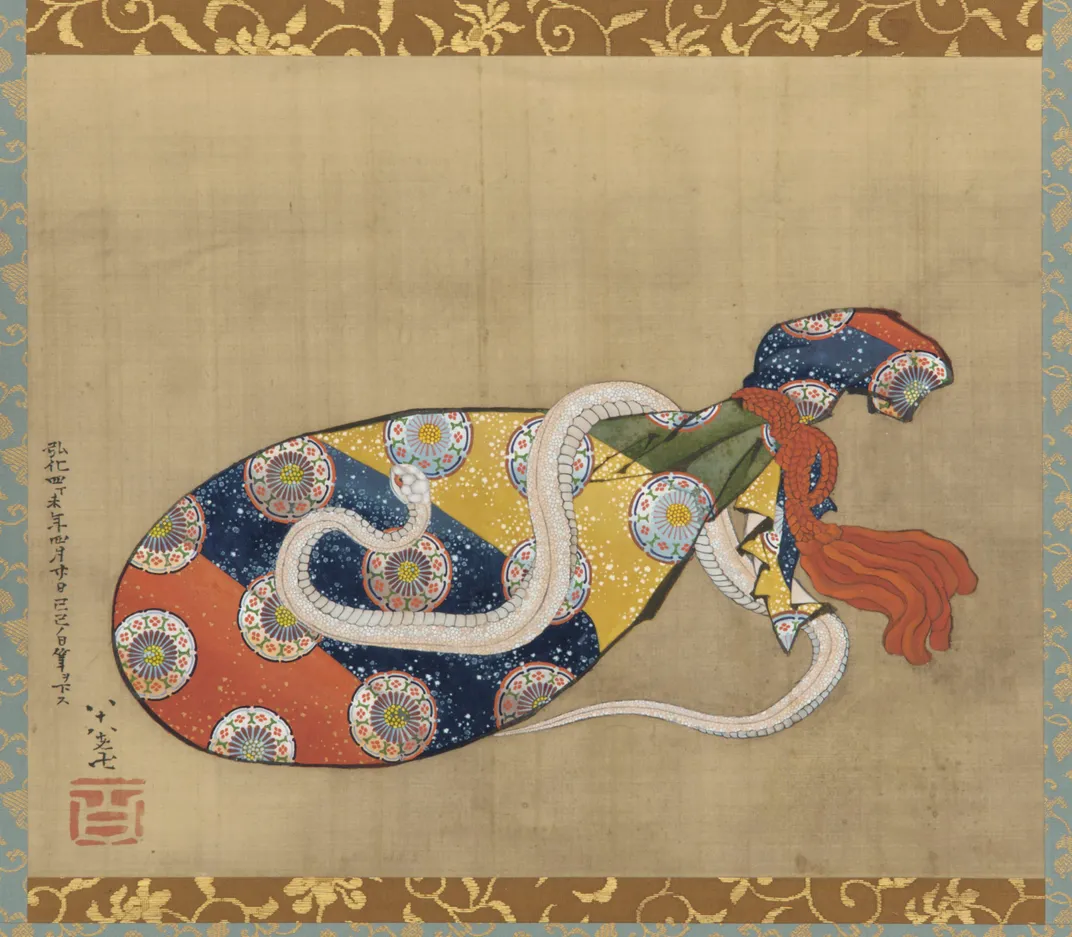

There is a variation of the theme, however, in an 1847 scroll painting, Breaking Waves—but it won’t appear until the second half of the exhibition in May. For preservation reasons, the works can only be shown for six months and must be stored away from light for five years.

The one Great Wave that does appear in the show, though, is one that won’t be widely circulated until 2024—when it appears on Japan’s ¥1,000 ($9) bill. Special accommodations by the Japan Ministry Finance allowed an enlarged reproduction of the upcoming banknote.

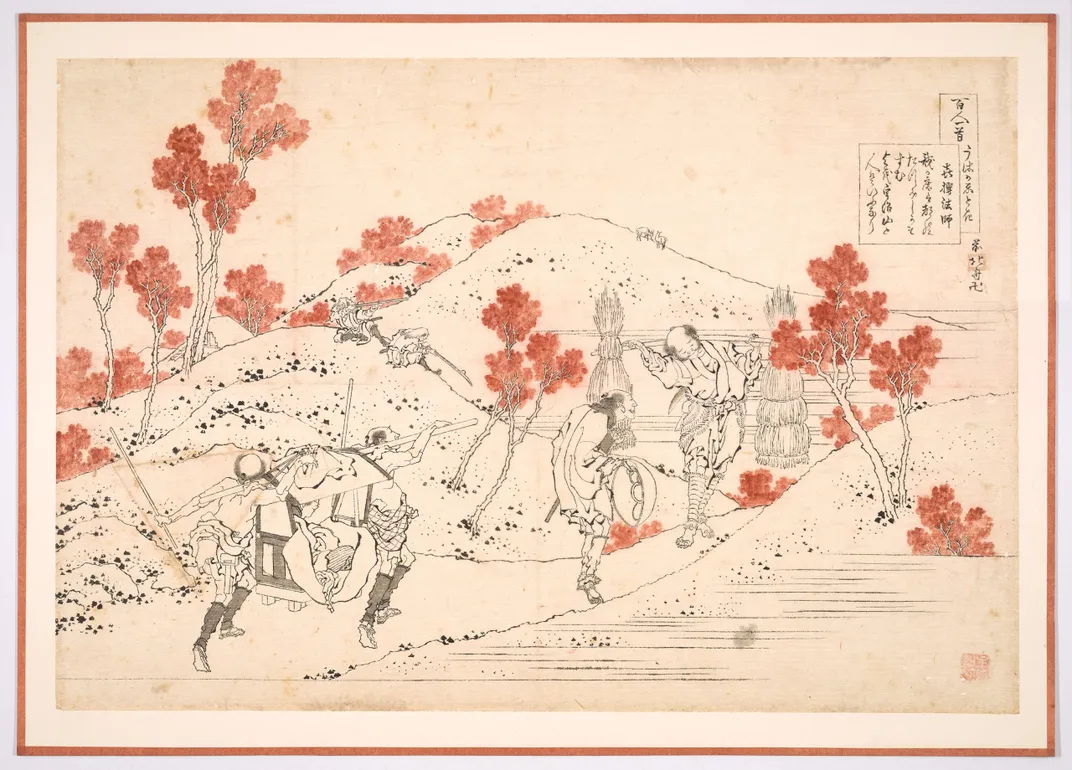

Hokusai is said to have disavowed any of the art that he made in the years before he turned 70. He began drawing at age 6 and worked as an apprentice to the ukiyo-e woodblock artist before he started producing his own notable work under several different names.

By his own account, it was only when Hokusai was 73, he wrote, that “I partly understood the structure of animals, birds, insects and fishes, and the life of grasses and plants.” By the time Hokusai turned 100, the artist said he hoped he would achieve “the level of the marvelous and divine,” and at his target age of 110, “each dot, each line will possess a life of its own.”

Hokusai didn’t make it that far, yet he lived and painted to the age of 90—“which of course was amazing,” Feltens says. “Ninety was a Biblical age at a time when the life expectancy was much much lower.” And the artist worked as if he knew his time was coming to a close.

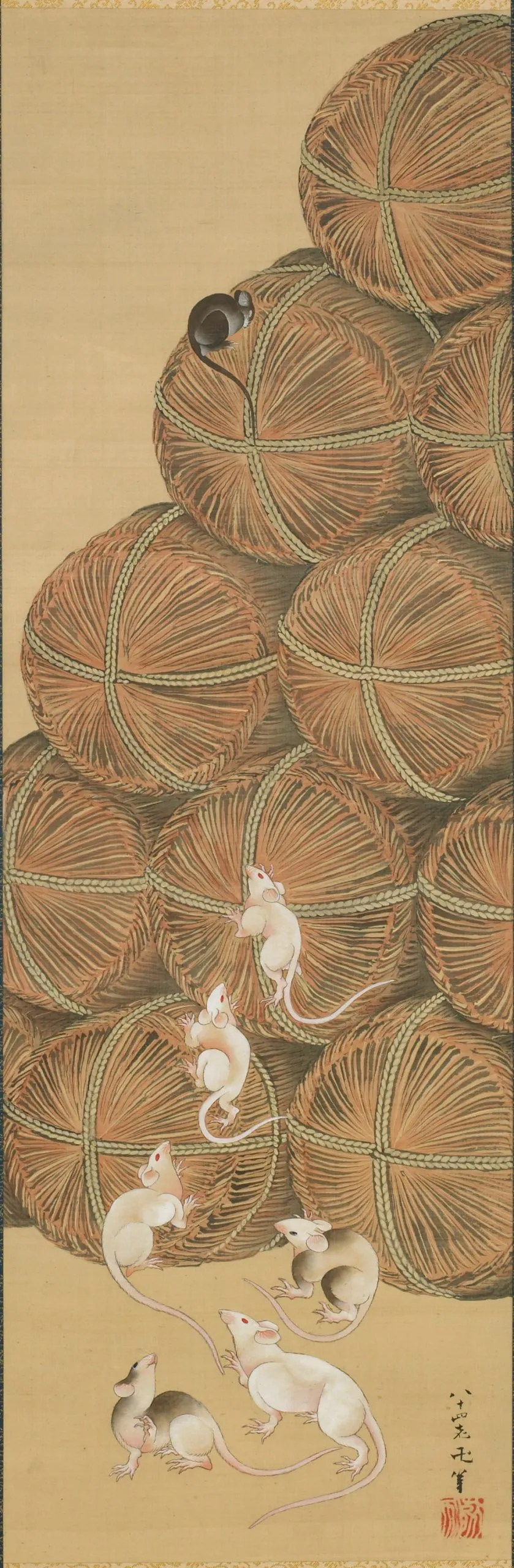

“His last decade was where he was actually his most prolific,” the curator says. “He made 32 paintings alone when he was 88 and 12 in the three months when he was 90. He wanted to churn out as much as he could.”

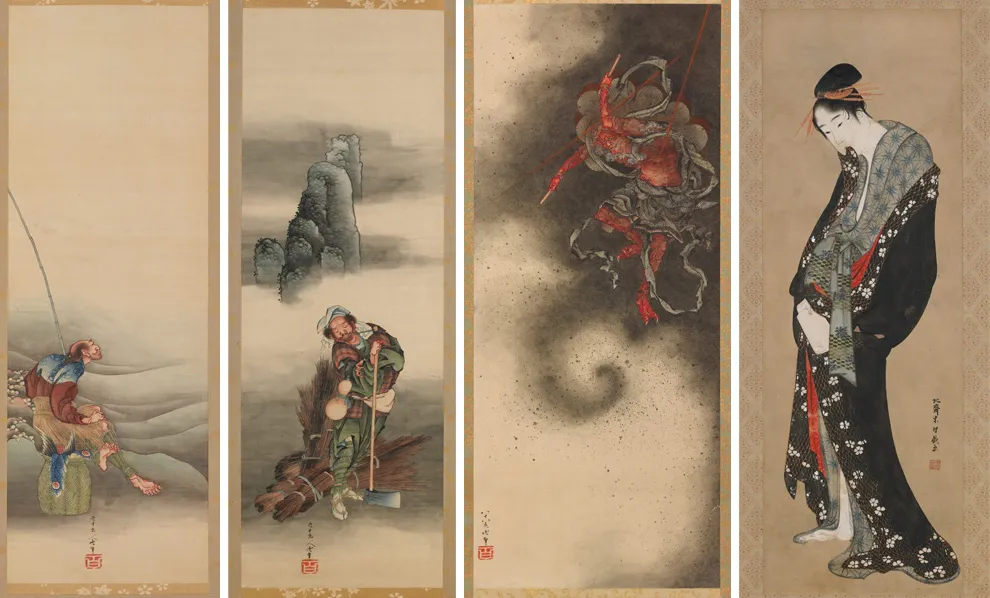

One of those late works is a standout in the show, a sinewy, crimson colored 1847 work Thunder God. Feltens notes “the vigor of this boundless energy of this lava-like body, with red skin, a symbol of vitality and strength with the face of almost a weary old man.” Only the wavering signature belies his actual age, 88, at the time.

“The Thunder God almost looks like computer generated imagery,” the ambassador says, “A CGI effect from Hollywood. It’s really, really powerful.”

Feltens says having the works in one collection for a century—and keeping them shielded for five years at a time between viewings—ensures that the colors remain vibrant—something that surprises visiting scholars. By museum rules, the works cannot be loaned out.

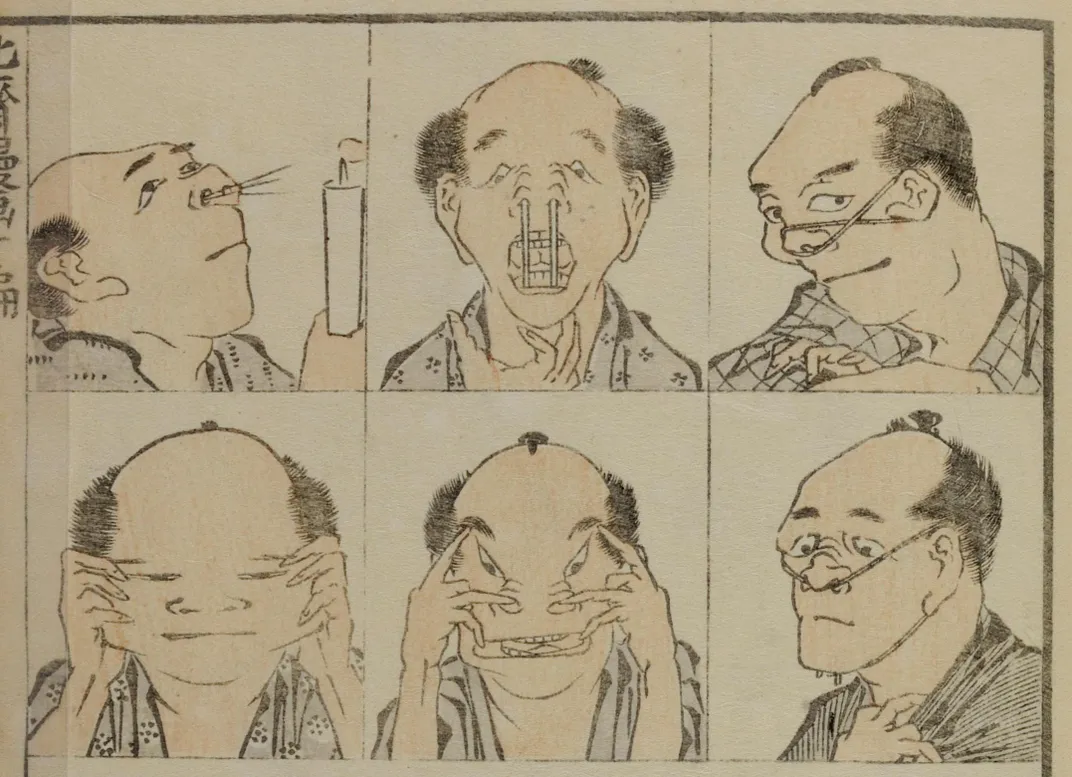

It is Hokusai who is thought to have popularized the term manga—used commonly today to refer to Japanese comics—back when he published a series of books of doodles and drawing exercises. The full range of 14 volumes on display are available electronically for the first time at the Freer.

They include studies, scenes of daily life, lessons for prospective students and an unexpected manual of dance moves. “This is how you can early-19th-century Moonwalk!” Feltens says, describing the book as “outlandish and absolutely fascinating.”

It was Hokusai’s blending of traditional Japanese art, with the influence of the realism found in Western and Chinese art that made his art seem so fresh in its time, and today. Sugiyama said he hoped “the exhibit will increase interest and curiosity about Japan, especially as we go into the year that Japan will host the 2020 Olympics and Paralympics in Tokyo.”

“Hokusai: Mad About Painting” continues through November 8, 2020 at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/bf/d7/bfd7e239-a7d4-41f9-95b4-1422034fa5c9/mobile-mt-fuji-opener.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/2d/52/2d52d93a-b35c-44fc-8224-fa29a4b11638/boy-looking-at-mt-fuji-social.jpg)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/RogerCatlin_thumbnail.png)